You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Children's authors promote tolerance following Brexit vote

As a slew of children’s books promoting empathy hit bookshelves, some kids’ authors say they feel a growing responsibility to counteract the UK’s “intolerant” political climate.

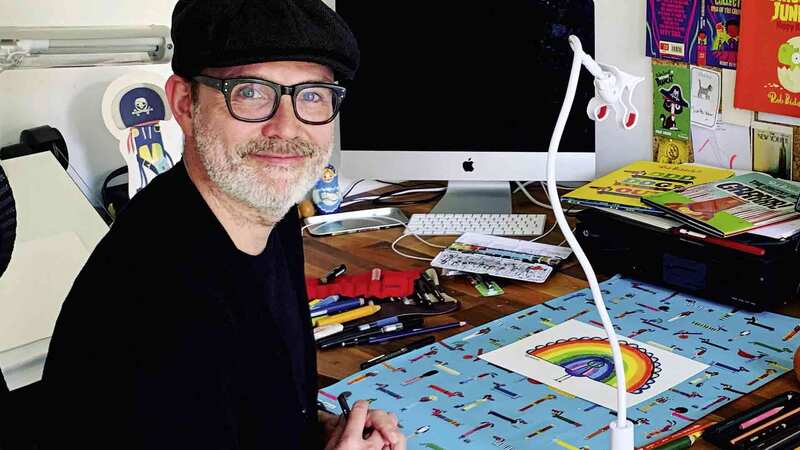

Author and illustrator Ed Vere said his new picture book about intolerance, Grumpy Frog (Puffin), was written as “a direct response to the Brexit campaign”. He explained: “There are so many highly intolerant voices in politics at the moment, it’s impossible that these ideas won’t filter through to children. I think children’s literature can show another way by teaching children how to think independently, to question their own behaviour and to attempt to understand others.”

The upcoming book from Nadia Shireen, The Cow Who Fell to Earth (June, Puffin), looks at “what it would feel like if you were new to this country and didn’t know how to make yourself understood”.

Shireen called the role of children’s book authors and illustrators “quietly political”, adding: “There are lots of loud opinions and not much nuanced thought in the information children are exposed to, so I’m happy to be on the side promoting empathy and tolerance.”

Kate Milner, author and illustrator of My Name is Not Refugee (The Bucket List), wrote her début book—which tells the story of a young boy and his mother travelling from their home in a war-torn country to a safe haven

far away—in an attempt to present children with another viewpoint to what she sees as a “fearmongering” public conversation about the refugee crisis, one “dominated by right-wing individuals”.

The book includes questions to promote discussion, such as “Where would you brush your teeth and change your pants?” on a page that shows refugees sleeping in a train station. “The idea is to get the reader to think about what it would be like to spend a night in such a place. I passionately believe that we need to give children tools to think about these issues.”

Similarly, Gill Lewis, whose A Story Like the Wind (May, OUP Children’s) follows a boy and the story he tells to fellow refugees while on a boat, said: “It’s important to see the human lives and stories beneath the headlines we see in the media”. She added: “With the rise in fascism across the world, we are seeing the normalisation of hatred, bigotry and prejudice. We need stories to help children develop empathy for others, because it is our only hope to develop a caring and tolerant society of the future.”

Upping the ante

Many authors said that though they have always felt a responsibility to encourage empathy and tolerance in their work, this has become more important in recent times.

Abie Longstaff, a former barrister who specialised in human rights, is the author of the Fairytale Hairdresser series (Puffin), which showcases a diverse society. She said: “As picture book writers, we have access to children right at the start of their reading life. That gives us a chance (and to some extent a responsibility) to represent a context of diversity, empathy, ethics and kindness.”

Robin Stevens, author of the Murder Most Unladylike series and forthcoming novel The Guggenheim Mystery, a follow-up to Siobhan Dowd’s The London Eye Mystery (August, Puffin), featuring a protagonist with Asperger syndrome, said: “I feel that, although I was always a writer who was interested in empathy, in post-Brexit Britain I have more to say than ever about tolerance and openness as positive characteristics.”

Waterstones Children’s Book Prize-winner Kiran Millwood Hargrave, whose latest book, The Island at the End of Everything (Chicken House), is inspired by the creation of the Culion Leper Colony, warned of the repercussions of reducing characters to one stereotypical trait, adding: “Children’s literature has always been an interesting bellwether for society. It is a scary time for children, as it is for those of us who perceive the world to be moving towards greater division and intolerance, but books are there to help navigate uncertain times.”

YA author Cathy Cassidy’s next book, Love from Lexie (June, Puffin), features a narrator who has suffered a loss in her childhood and deals with this by rescuing things. According to Cassidy, we read “not just to lose ourselves in a story but also to step into someone else’s shoes, and that’s a powerful step towards understanding others”. She added: “At a time when homelessness is skyrocketing, when many families rely on food banks and children often go to school hungry, we need that understanding and empathy desperately.”

Vere said that while empathy and tolerance are universal themes in children’s literature, the wave of new books centered on these ideas was “a sign of the times”. “Most writers are sensitive to the world around them. It would be surprising if there wasn’t a reaction to this aggressively political climate. It’s vital that we teach the next generation tolerance, empathy and the importance of independent thought if we want to live in a world where those values are held dear.”

A Lab of love

Cassidy and Stevens are among an increasing number of authors who have recently been working with Empathy Lab, an organisation that promotes the power of stories to build empathy. Its founder, Miranda McKearney, says more authors have been approaching the organisation since the Brexit referendum and Donald Trump’s election.

In 2017, Empathy Lab is looking to accelerate its activity by formalising its work with authors and author organisations such as Patron of Reading and the Society of Authors. It will also pilot a new Empathy Day in June, which will see the publication of an Empathy Reading Guide for parents and teachers, as well as running author empathy events in schools and empathy book promotions in selected public libraries.

McKearney told The Bookseller: “With increasingly diverse communities and classrooms, it’s vital that children can relate to people who may be different from them.”