You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Scottish and N.I publishers 'left behind' by antiquated defamation law

Scotland and Northern Ireland's unreformed defamation laws threaten to “undermine” publishing in the UK, according to English and Scottish PEN, with Scottish publishers particularly at risk of being “left behind”.

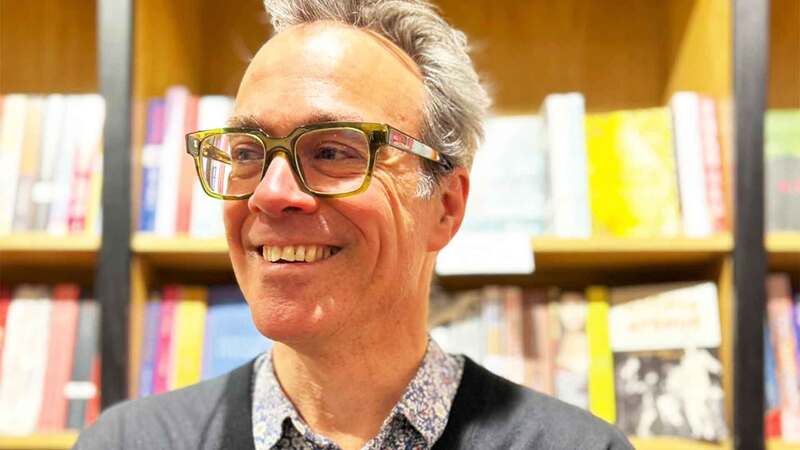

Robert Sharp, campaigns and communication manager at English PEN, said it was “essential” defamation laws were reformed, because the UK’s “wrong” three-tier legal system means it does not enjoy the same freedom of speech throughout.

Sharp said: “Publishers are cross jurisdictional. And where there is a question whether or not something can be said, lawyers will always advise publishers to publish according to the most restrictive law. The potential is that something which is fine to publish under English Law doesn’t get published."

In contrast to English law, which was updated in 2013, Scottish law currently lacks a “serious harm” test for legal actions for defamation, increasing the chance that claimants can sue for defamation even where the damage to their reputation is minor or hypothetical. Neither does it provide for a public interest defence or have a single publication rule.

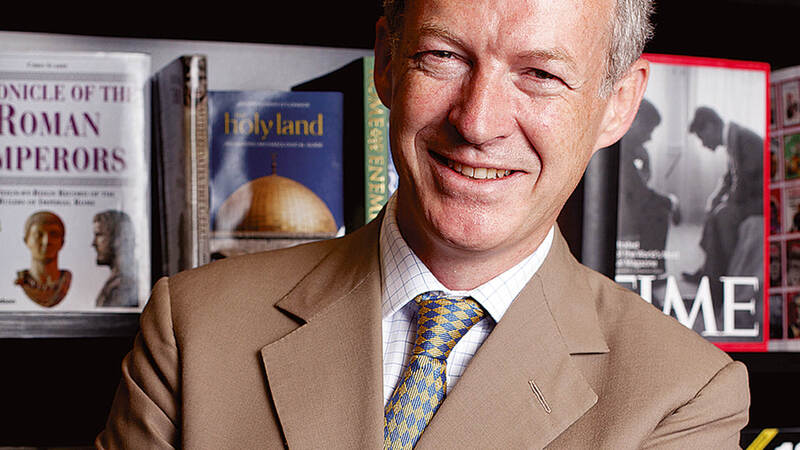

Stephen Barr, who succeeded PRH's Joanna Prior in the role of Publishers Association president on 18th May, called the Defamation Act 2013 only "a job half done”. At the time of his appointment, Barr said: "Let's see if we can complete that task...Until that loophole is closed we have not completed that job.”

Sharp added: "We welcome Stephen Barr putting freedom of speech high on the agenda. He is right to want to close that loophole. It is for the health of Scottish publishing. We don’t want Scottish publications to get left behind.”

In Scotland, the Defamation Law has not been reviewed in over 20 years, which means it does not take into account the internet. This also means that separate libel cases can be brought for different mediums of publication. “It’s a big deal,” said Sharp, “because you can reactivate a libel at any time. It’s the perpetual sword of Damucles hanging over publishers."

English PEN argued cases like that of author Jake Arnott, whose 2006 novel Johnny Come Home had to be withdrawn and pulped and his publishers Hodder & Stoughton forced to pay “significant” damages following a libel trial, were unlikely to have been brought had the test for serious harm been in place in 2006. The book fell foul of musician, Tony Rocco, who happened to share the same name as one of the book’s fictional characters.

Hachette's legal director Maddie Mogford told The Bookseller she disagreed the outcome of the Arnott case would have been affected by the new 2013 Act, but said there was a "greater reluctance" from within the legal system to take defamation complaints as far as the courts.

Ben Dunn, m.d. Blink for publishing, said 2013's law overall was "a swing towards freedom of speech" that favours the non-fiction publisher. Dunn, who has worked on books with high profile celebrities as Katy Price, Steve Coogan and Russell Brand, recalled a book he was working on last year that heavily criticised corporations. While he would not reveal specifically which title he was referring to, he said the changes brought about by the English 2013 Act - whereby companies have to exhibit serious harm in terms of serious financial loss - "allowed us more freedom".

"But you have to back up your claims," he said. "It's not like we can go about attacking everybody left, right and centre. It just means that if you're diligent, you have proof, and you do the work, then it's far less likely you get sued. For us in publishing, I guess it just gives you a bit more confidence when you're doing something that's controversial or you're dealing with a very high profile individual," he said.

Dunn said the discrepancies in Scotland and Northern Ireland hadn't been for him "a massive thing" but reform would help to "make it clearer".

Over 100 authors, including Val McDermid, James Kelman, Ian Rankin and Neal Ascherson, backed Scottish PEN's campaign for reform last year by signing a joint letter. It demanded Scottish law be made “fit for purpose” for the the 21st century, welcoming “[a new law] that acknowledges the existence of the internet, and enables journalists and authors to conduct a robust debate on matters of public interest”.

Novelists including Sebastian Barry, Roddy Doyle and Colm Tóibín, also sent an open letter urging Northern Ireland to change its libel law in 2013. It called for the executive to redress the "imbalance" between the different laws inside the UK and "breathe life into the right that underpins all other rights: our right to freedom of speech".

English and Scottish PEN are currently working with the Scottish Law Commission which is in the process of consulting on the issue, the deadline for which is June 17th.

Scottish PEN policy advisor Nik Williams admitted reform would be “a challenge” and said he would be surprised if changes were implemented this year, estimating any new law was more likely to follow in 2017.

In Scotland, legal threats issued to publishers have resulted in editors frequently having to take down or not publish material because of Scottish defamation law, Scottish PEN said. Williams said the issue was “as chilling” as court cases themselves and to some extent “even worse, because there is no transparency - we don’t know what is not being published”.

"It affects everyone,” Williams added. “It’s not just for publishers or for journalists...We need the politicians - who say they’re the most strong defenders of free speech and civil liberties -we need them to ensure that this reform does happen."

Northern Ireland’s Law Commission, meanwhile, has already consulted on revising its defamation laws, which are the same as England and Wales' were pre-2013. However, since the commission was dissolved in April 2015, its defamation reform project has been parked at the department of finance. English PEN said it hoped, and had been assured, the Northern Ireland executive will be publishing a report “soon”, despite consultation having been closed since February of last year. “We are urging the Northern Ireland executive to [publish soon],” said Sharp.

According to English PEN, only this year in Northern Ireland an author's memoir was shelved because the publisher decided there was too much of a risk of litigation. Another example is shown in the the case of Sky Atlantic, which declined to broadcast a documentary on scientology for fear of being sued in Northern Ireland.

“This is happening,” said Sharp. “We have heard of independents declining to publish books they believe are worthy because the risk associated with being litigated against in Northern Ireland cannot be discounted, which we were dismayed about, because it’s an example of the law being undermined by failure of reform in Northern Ireland."

Of both legal regimes, he added: "Where there is this ambiguity and discrepancy in the law there is huge potential for forum shopping and for mischief making."

Another consequence is the possibility legal costs will dent budgets for breaking new authors. "If publishers are spending money on libel, they’re not spending on new stuff," Sharp said. And the books that get binned, it won’t be the mainstream commercial titles, it’s going to be the experimental stuff - the first time authors, the challenging and the quirky things that are a bit of a risk."

Concerned parties can find out more about proposals for Scottish defamation law reform, and submit responses in consultation, on the Scottish Law Commission website.