You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

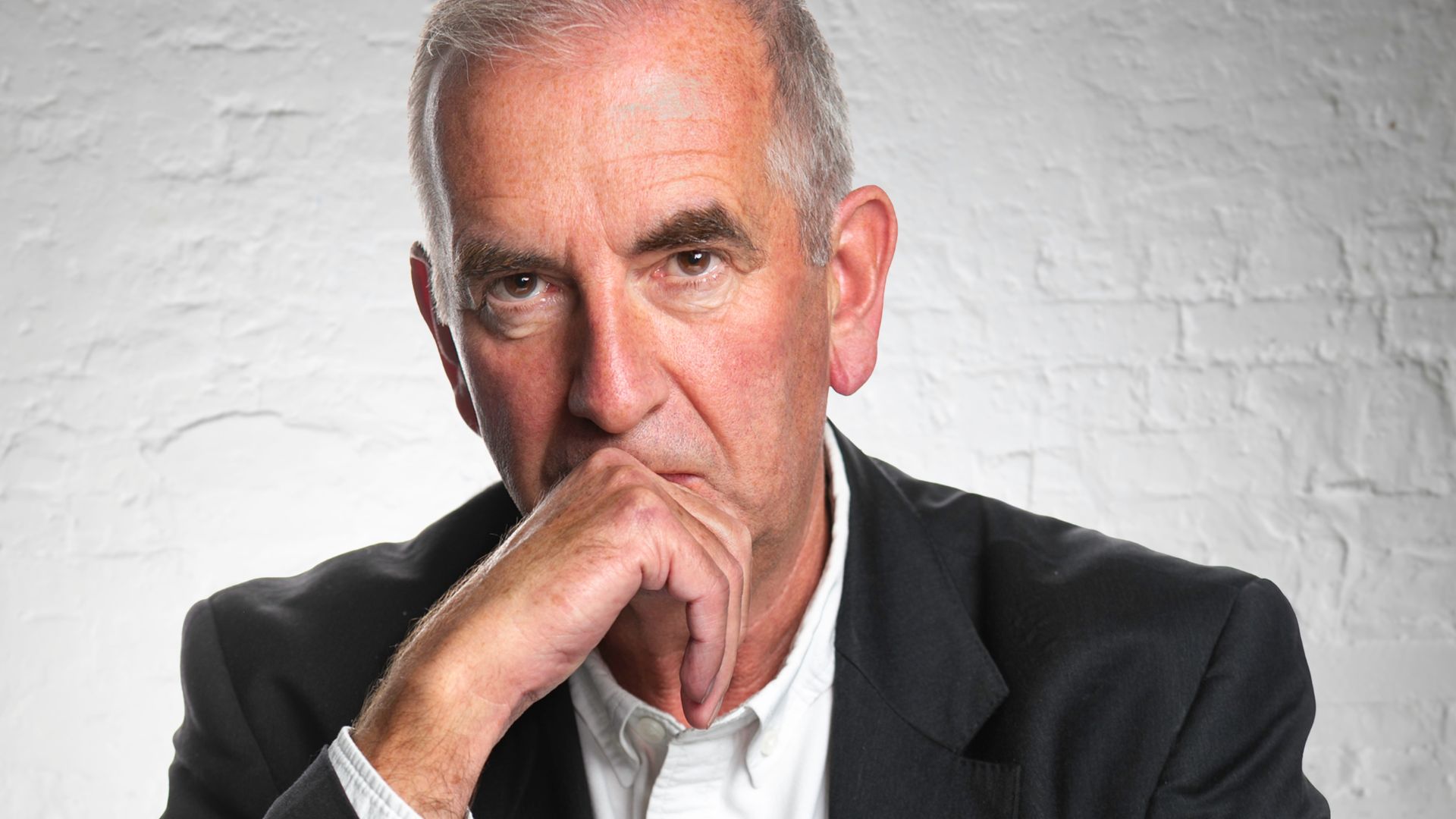

Robert Harris | 'Cicero had very good relations with Caesar but he was absolutely delighted to see him murdered before his own eyes'

Novelist Robert Harris is feeling a mix of relief and sadness, he says, at the prospect of parting ways with a figure who has been part of his life for the past 12 years. His acclaimed series on the life of Ancient Rome’s great orator Cicero, which began with Imperium (2006), reaches its conclusion this autumn.

Imperium and follow-up Lustrum—both recounted as if a biography written by Cicero’s secretary Tiro—showed Cicero’s rise as a self-made man, a lawyer climbing the political ladder without family connections or army backing, and achieving election as the consul of Rome at the age of 42 in 63BC.

Dictator recounts the events of Cicero’s final 15 years, beginning with his flight into exile in 58BC, following his failed opposition to the Triumvirate of Caesar, Pompey and Crassus. It’s a dark period, with those three big political beasts fighting it out for control of Rome, and succeeding in tearing the city’s precious democracy apart, with Caesar eventually ruling as a dictator. Meanwhile Cicero, a defender of the republic, fell victim to the manouevrings of Caesar’s heir Octavian and met a gruesome fate: his severed head and hands were nailed up in Rome’s Forum as a spectacular warning to others of the danger of political miscalculation.

From his Berkshire vicarage home, where a bust of Cicero has pride of place in the study, Harris notes that he was 46 when he began the trilogy, and is now 58 - younger than Cicero on his death at 63, but nevertheless old enough to be conscious of the passage of time.

“My children grew up during the writing of these books,” he says.

He has always stressed the contemporary resonances of the novels. “I wouldn’t have gone back to the period, if I hadn’t felt it had something to say to us,” he explains. “You have a double benefit [when you write a historical novel]: you re-create that world for the reader, yet at the same time it’s a commentary on our own time: whatever you select to write is inevitably trying to hold up a mirror to our own age, whether consciously or unconsciously. I do feel there are certain laws of politics that have held good for millennia: everything ends in failure; the very qualities that bring you to the top bring you down; and the electorate are fickle and will turn on you.”

Ancient Rome simply demonstrates those rules in a particularly raw and visceral way, he says, quoting D R Shackleton Bailey’s description of the Romans as “desperate masters of a larger world”. Harris says: “They lived on the edge without conscience. You could conquer the world, raise armies, ford rivers. It’s staggering really.”

Harris finds modern parallels for the major figures: Pompey, a soldier in politics, like Colin Powell; Crassus, yet another multi-billionaire who has bought his way to the top; and the patrician Clodius, “an Oswald Mosley figure, an aristocrat who likes to get down with the mob”. But Caesar, he says, is unlike anyone else: “Obviously a man of genius but extremely cold and destructive, and really a mass murderer—but because he succeeded and his family succeeded, he’s come down to us as a heroic figure. One can’t help but admire him, but I hope I convey some of the ambivalence that Cicero himself felt - Cicero had very good relations with Caesar but he was absolutely delighted to see him murdered before his own eyes.”

Harris thinks Cicero is unjustly unsung in comparison; he’s indignant that Shakespeare wrote about one but ignored the other. “Of all figures of the ancient world, we know most about Cicero—he left seven or eight hundred letters, books, speeches, an amazing record that shows him to be a man who is very modern, humane and not prone to violence, not a psychopath like Caesar. He makes endless mistakes; it’s the fact that he’s brilliant but fallible that makes him compelling. He’s also cowardly but brave, pompous but full of mischief—a very curious mix of qualities that I found very human and appealing.”

Writing about Cicero’s brutal death was a major challenge, Harris says. He found an answer in the books of philosophy Cicero wrote in his final years. “I don’t think it’s stretching the historical record to say that the only reason Cicero died as he did was because he decided to stand and fight, instead of retiring to live quietly in Athens, having armoured himself by philosophy to no longer fear death. So in a way he has the good death in the end that he craved, so there is a sort of triumph, although it’s ghastly. He was determined to stand for something and he did, and he lost, as he must always have expected was the likely outcome. He was duped by Octavian, who sacrificed him without the blink of an eye.”

Lustrum was dedicated to Peter Mandelson; Harris, formerly a political journalist, was close to New Labour before a high-profile falling out with Blair over Iraq, but Mandelson remains a friend. (By contrast, Dictator is dedicated to his daughter Holly, now an assistant editor at Headline, who studied Classics at university).

So what does Harris think of the contemporary political scene? It has been a “terrifically interesting” year, he says. “It’s the oldest lesson that if you lose the centre ground—if you let the enemy plant their flag on it—you are in dire trouble. Tony Blair [took it from] the Tories and now Cameron and Osborne have done it to Labour and it will be a long fight back. The logic for Labour is that they should elect Jeremy Corbyn, because that is their constituency now—they have allowed themselves to be disconnected from the centre of power.

“It seems to me the Tories are running a fairly competent social democratic government. The most significant thing is how Cameron, before he became prime minister, embraced gay couples. It made for great disillusionment [among traditional supporters] and a loss of support to UKIP, but it moved the Tories into a different era and I don’t think he gets enough credit for that. The speed with which he embraced governing with the Liberal Democrats, and the minimum wage—they are big moves actually. I’m not a great Cameron fan, he’s very poor on the smaller things—but on three big things, he’s left the other side gasping.”