You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Alan Hollinghurst’s seventh novel is a multigenerational exploration of modern Britain

Madeleine Feeny

Madeleine FeenyNew Titles Fiction Previewer

I compile the monthly New Titles: Fiction. A freelance critic and editor, I previously held ...more

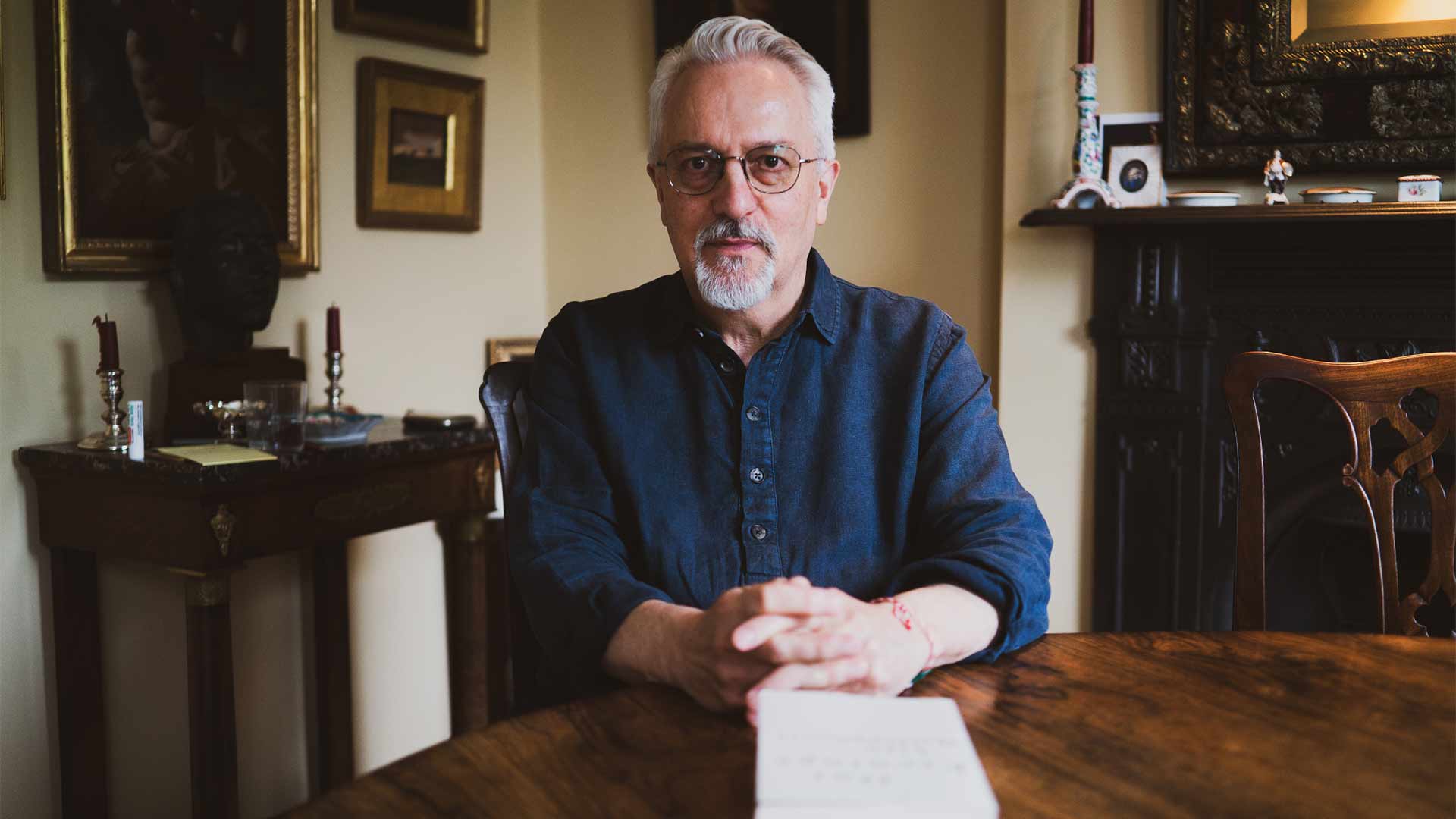

Alan Hollinghurst is the author of seven novels, including The Line of Beauty, The Swimming-Pool Library and his latest title, Our Evenings.

New Titles Fiction Previewer

I compile the monthly New Titles: Fiction. A freelance critic and editor, I previously held ...more

Publishers aren’t shy about declaring “event publications”—but in the case of Alan Hollinghurst, no hyperbole is needed. This is a writer whose appeal cuts across orientations and generations. Like one of his outsider protagonists being accepted into a wealthy family, this pioneering gay author has become literary royalty. An exquisite prose stylist who crafts elegant social novels in the tradition of Henry James, it is perhaps the mix of quintessential Englishness and radical sexual candour that make his books so popular. Over the course of a career that began with The Swimming-Pool Library and continued with novels including The Line of Beauty, winner of the 2004 Man Booker Prize, he has chronicled gay culture in Britain, illuminating the everyday realities of sex, love and discrimination and observing the impact of politics and current events on individual lives.

Coming seven years after his previous novel, The Sparsholt Affair, Hollinghurst’s seventh book, Our Evenings, is his third to span a long period—1962 to 2020—framing his story with the UK’s first attempts to enter the European Union and the aftershock of the Brexit vote. Luxuriously immersive, subtle and elegiac, it traces the arc of a life to paint a picture of modern Britain and is shot through with love, longing and delicious comedy (few have such a wicked ear for English speech patterns).

At 70, Hollinghurst is not playing it safe; he gives us his first protagonist of colour in Dave Win, a half-Burmese boy inspired by a fellow pupil at his primary school and an “unusual presence” in 1950s Berkshire. Having written many diverse characters who are “insider-outsiders” by virtue of their sexuality and class, he had long wanted to present a different racial perspective but was mindful of recent controversies over cultural appropriation.

From the Hampstead home where he has lived for more than 30 years, he says that “while it seemed to me very fascinating and urgent to imagine life from the viewpoint of someone moving through the world I’ve moved in, but set apart by their race, I saw that the last thing everybody wanted was some elderly white bloke telling people of colour what they think”. He perceived the possibilities of a biracial narrator, and that Burmese heritage would introduce some lost colonial history to the mise-en-scène.

It may seem like a window to an astonishing historic period to younger readers... My books explore British gay history. Things have changed an enormous amount

Born in 1948—six years before his creator—Dave Win is the son of an English single mother and a shadowy Burmese father. The novel charts his teenage years as a scholarship boy at a Berkshire boarding school, through painful love at Oxford University, his early acting career and relationships and on to later life. The story’s irregular, episodic tempo reflects the “indescribable experience” of time speeding up with age. “It’s a book about youth, which, before you know it, has turned into a book about death.” Lately, forgotten periods of childhood and adolescence have returned to him with remarkable clarity while midlife has receded.

Hollinghurst’s mother died aged 97, just before he finished his previous book. Losing her, and access to the Gloucestershire village that had long represented home, was a symbolic milestone that shook him more profoundly than he had expected. Although Avril Win is very different to his own mother, Our Evenings is a tender portrait of the love between a mother and son.

This relationship is marked by taboos—around the mystery of Dave’s father, Dave’s sexuality, and Avril’s relationship with a local divorcee, Esme. Unexpectedly, we find a queer family establishing itself in 1960s Berkshire, at a time when such things raised eyebrows and were being debated in the run-up to the 1967 Sexual Offences Act.

This mirroring disrupts the traditional, one-sided coming-out narrative, as both Dave and his mother take tentative steps towards happiness and self-acceptance against a prevailing backdrop of shame around homosexuality. “It may seem like a window onto an astonishing historic period” to his youngest readers: “My books explore British gay history, and over time become capsules of that history. Things have changed an enormous amount.”

Dave is always wondering what is visible to others, whether they are responding to his race or sexuality, as one difference “hides inside the other”. Yet he is no victim, but a talented, resilient person whose career proceeds in unexpected directions because of racial prejudice. The Sparsholt Affair was about a painter, so Hollinghurst wanted to explore another artistic discipline; when Dave tries to make it on the stage, he gets pigeon-holed playing Asian bit-parts, before finding his niche in experimental theatre. Hollinghurst hasn’t written a whole novel in first person for 30 years, since his first two, but given Dave’s different racial perspective it came to seem inevitable. “I felt that to write in third person would be, for me as a narrator, to assume a position of omniscience.” First-person narration allows intimate access but it’s also a way of withholding information, so it preserved the mystery of Dave’s paternity and the “psychological force” of his mother’s silence. You might expect novel-writing to get easier with practice, but not for Hollinghurst. The problem is not drying up but having too much material. “Once I’ve got two or three people talking in a room, I’m happy, that’s what I love doing. But there’s a lot of anxiety about the structure.”

The novel’s political dimension, while less significant than that of The Line of Beauty, is derived from the Hadlows, left-wing philanthropists who sponsor Dave’s scholarship. Their “thoroughly obnoxious” son, Giles, keeps popping up to haunt Dave, before becoming impossible to ignore as Brexit Minister. His parents’ bemusement echoes that of the disappointed remainers, including Dave. This note of sadness, bookending Our Evenings, serves as a sobering reminder that, however far gay rights have come, they are “constantly being threatened by the revival of the right”.

But for now, let’s leave this charming literary great in his Hampstead element. As usual, he finished the book vowing never to write another, “although maddeningly I did find myself jotting down a couple of little, tiny ideas”.