You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

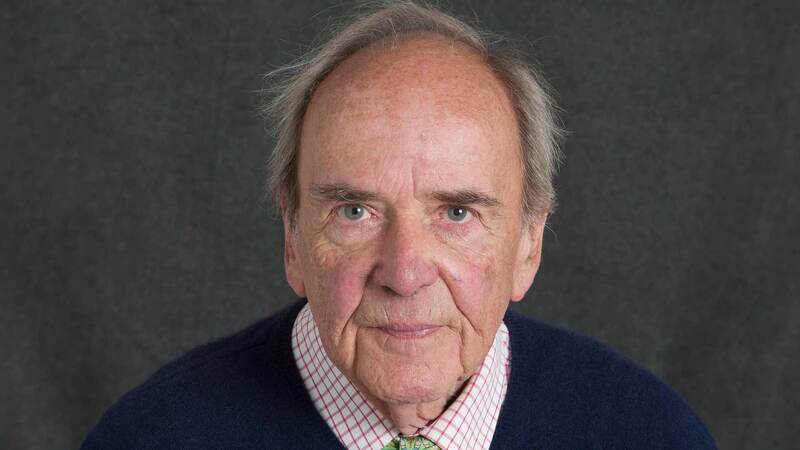

Alex Pheby | 'I like to try things. I like to see how they work and see whether I can do them'

Republic of Consciousness winner Alex Pheby pivots from literary fiction to fantasy with his latest, the first novel set in the city of Mordew

Alex Pheby warns his readers, at the start of Mordew, about the “many unusual things” they are set to find within the forthcoming 600-odd pages. A cloud of bats made from diamonds. Clay figures animated by blood sacrifice. Hordes of feathered monsters, made of fire. Creatures that are born directly from the muck. The sheer exuberance of the list is a delight, and a dizzying introduction to one of the most darkly enjoyable fantasy novels I have read in ages; vast, gothic, Gormenghasty in the best way, and bursting with invention and joyous grotesquery.

Set in the city of Mordew, a place lapped by Living Mud and ruled over from above by the mysterious Master, Mordew is the first in a trilogy. It follows the story of Nathan Treeves, a boy from the slums whose father is dying and whose mother is selling herself to keep her family above water (or Mud). But Nathan has a power—an “Itch”—of his own, if only he dared to use it

In fantasy fiction, you can really pile on the magic, I think, and everybody likes it—and I like writing it.

The young boy who has unexpected powers: from The Dark is Rising to Harry Potter, it’s not an unusual fantasy trope. But that’s all part of the fun for Pheby. “I don’t think anyone ever expects you to kind of reinvent the wheel, and I think there’s no need to. I think there is plenty of room in those tropes to do something different,” he says. “People like those stories of a special child, and then you can patchwork onto that a whole bunch of other stuff that they might not be so familiar with, like philosophy and questions about agency, without losing that sense that you’re enjoying something that you like.”

Pheby is an associate professor of creative writing at the University of Greenwich. His previous works include the literary, and well-reviewed novels Lucia—inspired by the troubled life of Lucia Joyce, it won the Republic of Consciousness Prize for small press-issued titles—and Playthings, a look at a 19th-century German judge’s experience of psychosis, which was shortlisted for the Wellcome.

“If you were to look at the books that I got published, you’d think all I ever wrote was literary fiction,” says Pheby. “But actually I’ve always written genre fiction and literary fiction at the same time, it’s just no one wanted to buy the genre fiction. I’ve written science-fiction, crime, all sorts of stuff. One was a kind of war novel about a guy who was hidden under the floorboards in a prisoner of war camp, imagining walking the hills of his childhood England. I like to try things. I like to see how they work and see whether I can do them. But I don’t know whether any of those will see the light of day, to be honest.”

He had thought that next on the slate would be a literary novel about the actor Sylvia Maklès, who was married to the French philosopher Georges Bataille, but when his publisher Galley Beggar Press heard about Mordew it was interested, and “it was nice to step out of the literary biographical fiction kind of niche and do some fantasy world-building”.

A glance to Vance

Pheby has always been steeped in fantasy. A “heavy duty Dungeons & Dragons geek” as a child, he had a “geeky teenage crush” on science-fiction legend Jack Vance as a teenager and collected everything he had ever written. (One of his unpublished novels is “very much a tribute to Planets of Adventure by Jack Vance”.)

So the author doesn’t come to fantasy with any of the disdain which literary novelists sometimes display towards the fantastical; rather the opposite. “That’s not me at all—I’m the other way, if anything,” he says. “I think I find myself being slightly snarky with literary fiction, despite the fact that I also write it, because I think writers of literary fiction imagine there are no genre conventions to it. But there definitely are and they’re just as obvious when you know the rules of them as the conventions of something like romantic fiction or crime fiction.”

Pheby first embarked on writing Mordew around 10 years ago, and describes it as “a serious attempt to do something world-buildingy and fantasy-based with the same kind of ideas that I’ve always run with, essentially, loneliness, social exclusion, fantasy and madness, and how those things are linked together”. It’s very much, he says, the same ground that he treads in his literary fiction.

Poor old Nathan, in Mordew, is thrown from pillar to post, taken up by a street gang which throws him into burglaries with gay abandon; whisked into a world of privilege; sent on a sea voyage. “I’m interested in the absence of agency in people’s lives, the extent to which they’re buffeted around by history and forces beyond their control, and how a person reconciles themselves to that fact, mentally, and how you live in a world in which you don’t really have any control,” says Pheby. “Because I don’t really feel that we do have control over the things that happen to us.”

One of the joys of Mordew is Pheby’s inclusion of the huge dogs Anaximander, who talks, and Sirius, who doesn’t. Side note, because information about dogs is always super important: Sirius is named after the dog of Galley Beggar publishers Sam Jordison and Eloise Millar, and Pheby has his own Anaximander, a five-month-old Shih Tzu-Pomeranian cross. Neither of them, sadly, can talk, although Anaximander is “quite yappy”.

“Once you’ve had the idea, and it seems cool, there’s nothing in fantasy that says you have to pare that down, you can just go wild with it and do whatever it is that comes into your head, providing it makes sense for the story,” says Pheby. “That’s something that I also enjoyed as a relief from the quite spartan realism of something like literary fiction, which requires you—this is one of its genre conventions—to keep things muted, and to keep things within the possible and within the real and within the plausible. Should you ever find yourself drifting off in the other direction, then you need to rein that in, because otherwise people won’t fall for it, whatever it is they’re supposed to be getting out of literary fiction. In fantasy fiction, you can really pile on the magic, I think, and everybody likes it—and I like writing it.”

This is clear: the book ends with a fabulous 100-plus- page glossary about the world Pheby has created. (“Alifonjer(s): Ancient megafauna now extant only in the Zoological Gardens in Mordew. Famous for their enormous size, prehensile snout, and mournful visage, it is supposed that these creatures are highly intelligent, though, as a species, they were unable to avoid being rendered almost extinct.”)

Pheby has been managing to fit writing in around his son’s GCSE revision during lockdown, and is well on the way to finishing the second novel in the Mordew trilogy, which has been signed up by Tor in the US. It will publish in September, with Lucia also lined up for US publication in June. His speed, he estimates, is around 1,500 words an hour, once he gets going, meaning that his stash of yet-to- be-published novels is now pretty large.

“I’ve been going since I was about five,” he jokes, “so there’s a big backlog. I didn’t publish my first novel until I was 39, so I’m always amused to see these prizes for ‘emerging writers’ capping out at 30 years old. I think it’s a privilege to be able to finish a book before you’re 30 and get it published, full stop. Because lots of us have to work just too hard at jobs that don’t allow you the time, or you don’t have the connections, or it takes you a long time to kind of get revved up. You have other things going on in your life that just mean you can’t do it. So I think a lot of writers, whether they admit it or not, have a sizeable back catalogue hidden away in their hard drives.”