You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

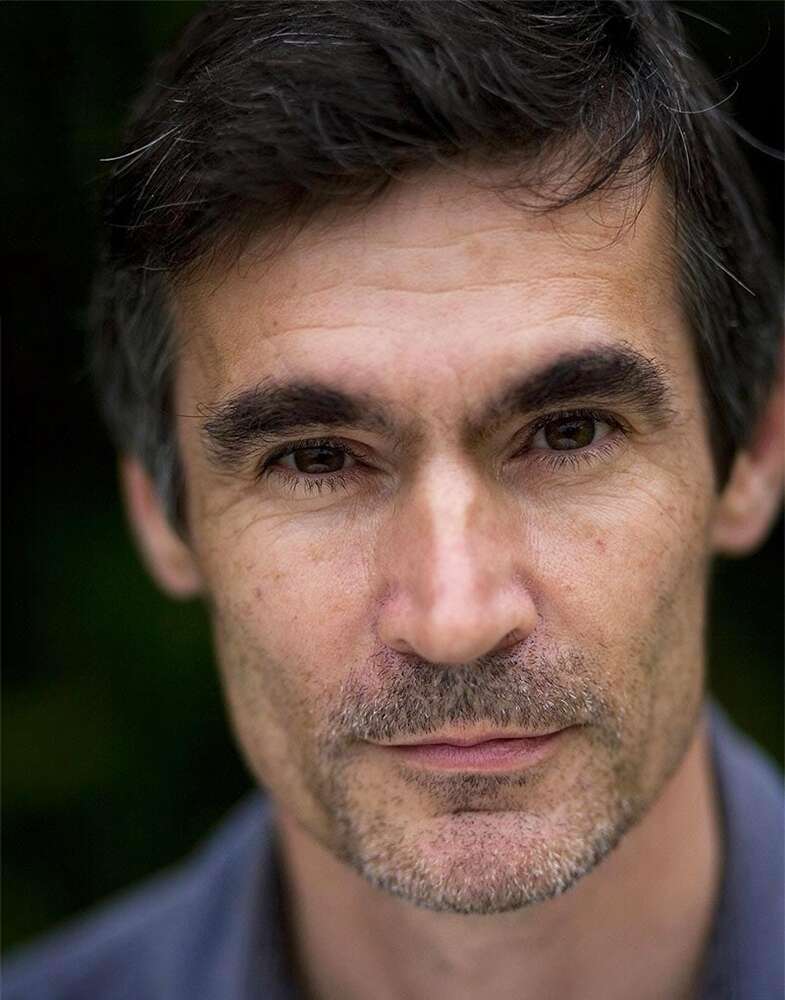

Andrew Miller | 'The moment you try to play safe you are likely to produce work that is of no interest'

Andrew Miller’s seventh novel, The Crossing, opens with a young woman falling—in such a quiet way that it is a barely noticeable occurrence—from the deck of a boat in dry dock straight onto the brick rubble below.

Badly injured, she gets to her feet and attempts the impossible, to walk, before sinking back to the ground and being rushed off to A&E.

This event — which marks the start of the strange courtship between the young woman, Maud Stamp, and her fellow student Tim — is a striking opening to the novel, and a striking introduction to its enigmatic central character. A biologist, an amateur sailor who loves nothing more than practical work on her boat “Lodestar”, partner to Tim and later a mother to Catherine, Maud’s intense self-sufficiency makes her baffling to those around her. The tattoo inscribed on her arm—“sauve qui peut” [“every man for himself”]—is indicative of her guiding principle. A born survivor, she does not express her emotions in a way other people find easy to recognise, even when tragedy strikes at the heart of her family.

The Crossing is divided into five parts, with the earlier sections written in realistic vein, the settings emphatically mundane: Reading, Swindon, Maud’s office after she starts working at drug company Fenniman Laboratories. But as the novel progresses, it takes a twist into odder realms: Maud’s mental stability buckles following the death of her daughter, and she heads off alone on a long and difficult sea voyage into the Atlantic, and from there on to a mysterious coast.

Interviewed in a quiet alcove between the shelves of Topping & Company Booksellers in Bath — Miller lives in a village not far from the city — the author smilingly explains that he was beset with doubt and hesitation throughout the writing of the novel, although doubt is part of “the process”, he adds.

For a start, while his fiction has always swung between historical and contemporary settings, he was unsure about making such a departure from his last book Pure, set just before the French Revolution, which won him the 2011 Costa Book of the Year. “Because Pure had some success, there was a feeling that maybe it would be unwise to move away,” he explains. “But actually I can’t think like that. In the end you write the book you need to write, the book that’s pushing you most strongly.”

When he broached his idea for The Crossing to his long-time publisher Carole Welch over lunch, he wasn’t sure it was something he could pull off. “It sounded to my own ears such an odd book that I almost apologised for it,” he says. “Being Carole, she didn’t say anything, just carried on cutting up her asparagus. The next day she emailed me and said, ‘Yes, I think you can do it.’”

The doubts persisted: “I kept asking Carole, ‘Please tell me I can stop now.’ She just said, ‘No, it’s OK, keep going.’” At one point, Miller wrote a completely different ending to the one he had planned for the book. “Carole ignored it. She knew what was supposed to be coming and realised this wasn’t it. I think she likes us—her writers—to work right at the edge of what they think they can do, or even perhaps some distance into what they think they can’t do.”

Animal instinct

Maud is Miller’s first female central protagonist, but he points out links to figures in his earlier work: James Dyer, the surgeon who can feel no pain, from his d ébut Ingenious Pain, or Alec in the novel Oxygen, whose ability to express his emotions is stifled. Writing his latest character presented a new kind of challenge, though: “Her old judo instructor thinks she reminds him of his dog,” muses Miller. “I wanted someone who had this animal alertness but who was not reflecting hugely on herself. She is living in the moment. She’s the sort of person who would never keep a diary, [she’s] in no sense incapable of love but not someone who is going to give eloquent testimony to her feelings. If you have a central character, you want someone who is lucid in their emotional life—and she’s not at all. And then I put myself alone on a boat with this person!”

As the father of a 10-year-old daughter, he felt discomfort over the fate of Maud’s child. “I didn’t want to write about a child coming to harm. I shied away from those scenes. You get into all sorts of crazy ways of thinking, ‘Could I put my child at risk even by writing this?’” And his challenges weren’t just emotional and creative—a boyhood sailor, he took up the sport again for the purposes of the novel, making the lengthy journey from Cornwall to the Hebrides in a traditional wooden sailing boat. “I’m not a good sailor,” he admits. “Sailing is a strange thing, you’re cold most of the time and usually covered in bruises because a boat is a small place that moves around, so you’re constantly whacking into stuff.” He won’t be keeping it up.

Ambitious fiction

But ambition for his fiction, the wish for “a book that it would be difficult on page 10, 15 or 50 to know what it was about . . . a book that wouldn’t reduce down; the unpitchable novel” is what drove Miller forward. “Before I started writing this, I found myself in a strange situation of picking up lots of novels—good novels, perfectly well written by intelligent people—but not being able to read them. They just slipped out of my hands somehow. I felt, ‘I know what this is.’” Miller was looking for a quality to leave him thinking: “What was that? It went in, it feels good, I don’t know what it is, but somehow it is expanding.”

As a rule of thumb, be ambitious, be free, write the book you want—and don’t lose your nerve.

He cites Denis Johnson’s novella Train Dreams (Granta) as a book in which he found that quality. ”This funny little book, full of anecdotes, following the life of this unimportant man in the mid-19th century Midwest, dropping in at his life at odd times. I thought, ‘I like this, because I don’t really know what it is. But there is something, an intensity of glance, the way he looks on this man’s life.’ I find that intense glance in another American writer, James Salter, whom I’m a massive fan of, particularly his book Light Years [Penguin] which seems to break all the rules—superb, confident writing, but high-risk writing.”

It’s something he tries to impress on his creative writing students at Arvon, or at the Guardian masterclasses he teaches. “The moment you try to play safe you are likely to produce work that is of no interest. As a rule of thumb, be ambitious, be free, write the book you want—and don’t lose your nerve.”

Metadata

Imprint: Sceptre

Publication: 27.08.15

Formats: HB (£18.99)/EB

ISBN: 9781444753493/9781444753516

Editor: Carole Welch

Agent: Simon Trewin (WME)

Photo credit: Abbie Trayler-Smith