You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Ann Cleeves talks about her iconic characters and the hallmarks of crime

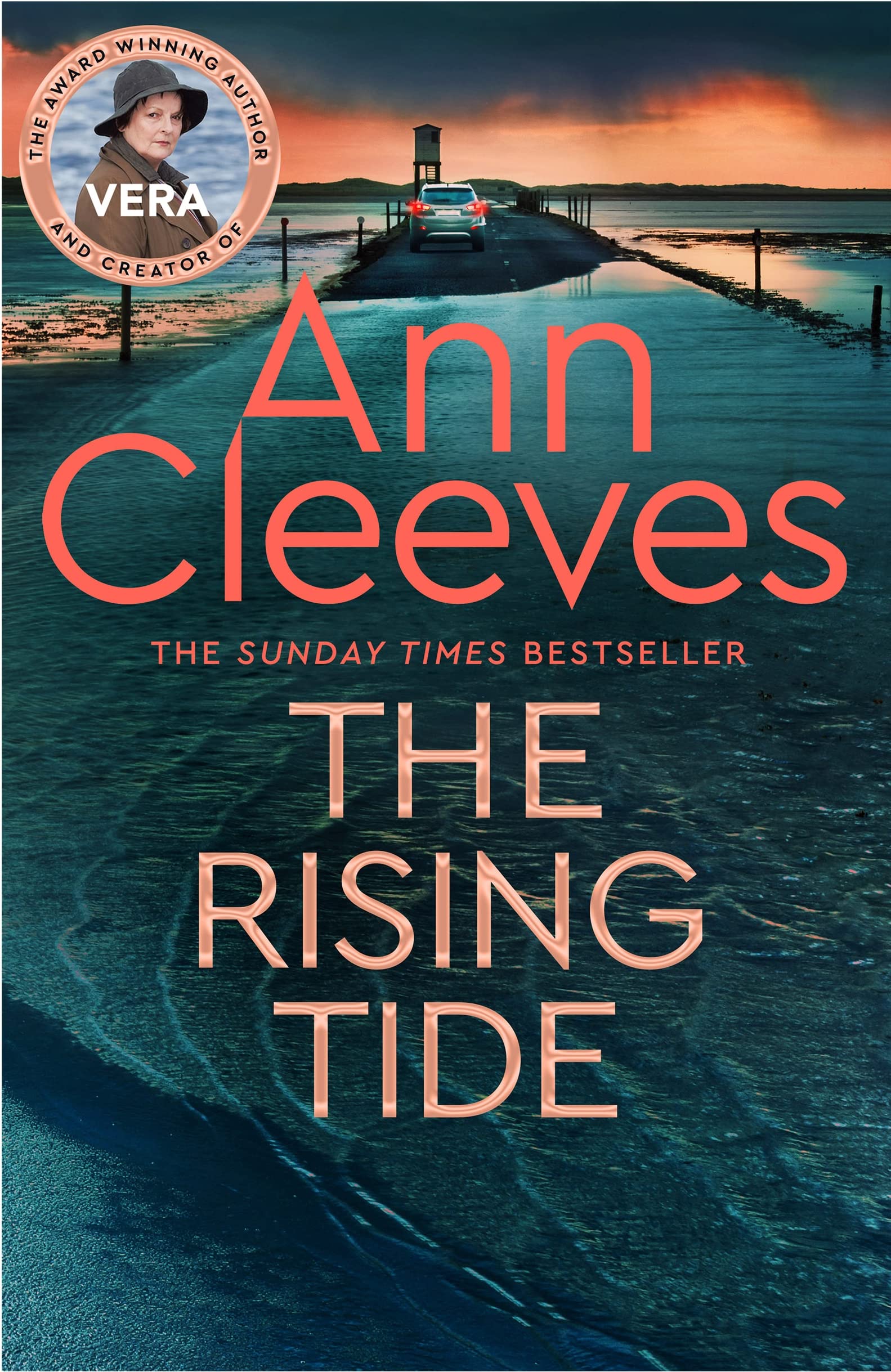

Characters face their own mortality in Ann Cleeves‘ tenth novel in the Vera Stanhope series.

It’s hard to believe that Ann Cleeves, the bestselling author of some of the UK’s most beloved crime series—her scruffy, middle-aged detective Vera brought to life by Brenda Blethyn; Shetland’s Jimmy Pérez immortalised by Douglas Henshall—only became a full-time writer in 2006. She’d written more than a dozen books by then, but was also working as a reader development officer in libraries, to keep the money coming in.

Cleeves is in the Pan Macmillan offices today, where the publisher is about to kick off celebrations to mark the 30 years she’s been with them. Thirty years, six million copies sold worldwide, Pan Macmillan says; 38 weeks in the UK top 10, millions of viewers of her television adaptations, and a raft of reissues and appearances planned over the next six months. The earlier half of those 30 years, however, wasn’t quite so gilded.

I just didn’t fit in, I heard someone on the bus saying I looked like I’d just come off the farm

“My husband Tim worked for the The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, we had two children and we couldn’t survive on his wage, so I had to work. Writing is fairly precarious,” Cleeves says. “It wasn’t until 2006, when Raven Black [the first Shetland novel] won the Gold Dagger and sold overseas, that I could give up the day job.”

Cleeves has had a wide variety of day jobs, from probation officer to peripatetic childcare officer, to cook at a bird observatory on Fair Isle in Shetland. It’s probably one of the reasons her books are so humane, so well observed, as well as being cracking mysteries. The latter job, though, was also the reason she met her late husband Tim, an ornithologist; she’d dropped out of university (“I just didn’t fit in, I heard someone on the bus saying I looked like I’d just come off the farm”) to work in childcare for Camden Council. At just 19, it was “a lot of responsibility”, so she jumped at the chance when she heard a friend was off to be assistant warden at the bird observatory on Fair Isle, and mentioned there was a job as assistant cook going.

Tons of potatoes peeled and scones baked later, she’d met visiting ornithologist Tim there, and got engaged. His job took them to the nature reserve on Hilbre Island, at the mouth of the Dee Estuary. Cleeves started out commuting into Liverpool to train to be a probation officer, but stopped when crossing the tides pregnant became too much. The islands are uninhabited; birds aren’t her thing, there was little to occupy her, and she began to write.

Bursting open the door

“If you’re not really into birds, there’s not much to do there, so that’s where I started,” Cleeves says. “I thought I was going to write a great novel about social justice, it was going to be a great work of literature. I’m really quite good at character, I can build a character that people can believe in, but you can’t just have them sitting around chatting in a room, something’s got to happen. And I couldn’t think what to make happen.”

Her comfort reading was crime fiction, so she decided to kill someone off, “and then I was away, because you’ve got that structure with traditional crime fiction. You don’t have to worry about the plot, really. You’ve got a body, you’ve got a limited number of suspects. And you’ve got some form of resolution. Somebody said it’s like a corset to hold you up.”

Her first books featured George Palmer-Jones, an elderly birdwatcher solving mysteries with his wife Molly; A Bird in the Hand, her début, was published in 1986. The family moved to a village in Northumberland, following Tim’s job as a conservation officer for the RSPB, and the Inspector Ramsay series—like Vera, based in Northumberland—launched in 1990, in A Lesson in Dying. Cleeves held all sorts of jobs over this period, from running a playgroup to selling flights for British Airways, getting up before 6 a.m. to make time for her writing.

I think Vera grew out of those indomitable women who ran things

The first Vera book, The Crow Trap, was published in 1999, but was by no means an instant hit. Cleeves’ editor had asked her to write a big standalone novel of psychological suspense, without a series detective in it, so she set out to tell the story of three women doing an environmental survey up in the Northumberland hills. Cleeves never plots before writing, and she got “really stuck” with the story.

“Raymond Chandler says, if you’re stuck with a book have a guy burst through a door with a gun. I don’t do guns, but I was writing this funeral scene and they were in the chapel, so I had the door burst open. And really, almost literally, in came Vera, fully formed. I had a name, and described her as looking more like a bag lady than a detective, and she was carrying her notes in a plastic carrier bag,” says Cleeves. “I think she came from some of those single women that I knew when I was growing up in the mid-1950s, women who had had real responsibility during the war. But then the men came back, and if you were married, you had to give up work, so they decided they’d rather be single than be 1950s housewives. I think Vera grew out of those indomitable women who ran things.”

Cleeves loves the fact Vera doesn’t care at all what she looks like, that she’s in charge of a team but, refusing to be patronised herself, will not patronise those she works for. She’s gone on to star in nine books to date; the tenth, The Rising Tide, is out in September in hardback, and sees the detective investigating a group of friends, one of whom died during a reunion on Holy Island decades earlier, and one of whom has just been found hanged.

Cleeves wrote it during lockdown. “I think it’s about people facing their own mortality,” she says. “Although it’s not really about lockdown, it is about that time when we’re all thinking that life is more precarious than we thought it was. So it’s about older people who’ve been friends for years coming to terms with that, realising that they were getting older too, and that you couldn’t really fight it.”

The first "Vera" television series aired in 2011, with actor Brenda Blethyn a pitch-perfect version of Cleeves’ detective (“I do have Brenda in my head now when I write”). The Shetland adaptations began in 2013, and Cleeves’ most recent series, starring DI Matthew Venn as he returns to his Devon hometown and the closed religious community he grew up in, launched on ITV last autumn.

In it for the long haul

Cleeves started writing the Venn series after the unexpected death of her husband in 2017. She’d gone back to Devon, where she grew up, to stay with her best friend, whose parents had belonged to a small religious group. “I’m thinking, if you’ve grown up in that, and you’d lost your faith, you would be cast out. And if that had happened to you, you might be attracted by something like the police service, because it would give you that sense of community and honour and duty. And it might be quite fun to have a straight-laced, uptight police officer who was a part of that.”

Venn is gay, and happily married—partly a celebration of the gay couple, friends of Tim’s and hers, who had helped Cleeves after his death, partly because “it really fitted into the relationship with the mother and the plot [of The Long Call, the first Venn novel], because it’s so much harder to get a reconciliation if you’re gay”. It was read by three gay couples before it went to the publisher, including her old friends, but Cleeves admits that while she loved writing about the relationship, “it is a bit tricky, with the whole thing about appropriating other people’s lived experience and do I have the right to do it”.

The latest Matthew Venn, The Heron’s Cry, was out in February in paperback. Cleeves likes to alternate between series, because she “would get very bored if I were just doing one”. There’ll be no more Shetland books—“eight was enough for Shetland, I just ran out of things to talk about”—but Vera and Matthew, thank goodness, are still in it for the long haul.

Still one for multiple jobs, Cleeves decided in 2020 to sponsor a new “Reading for Wellbeing” project in the north-east, in which community reading workers enable access to stories and reading to help improve the health and wellbeing of those in need of support. There are now nine of these workers. “It’s slow, and there probably won’t be a dramatic decrease in demand on the GP—but just for a couple of people, it’s going to make a real difference,” says Cleeves, finishing off her sandwich and crisps, and looking quietly, rightly, proud.