You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

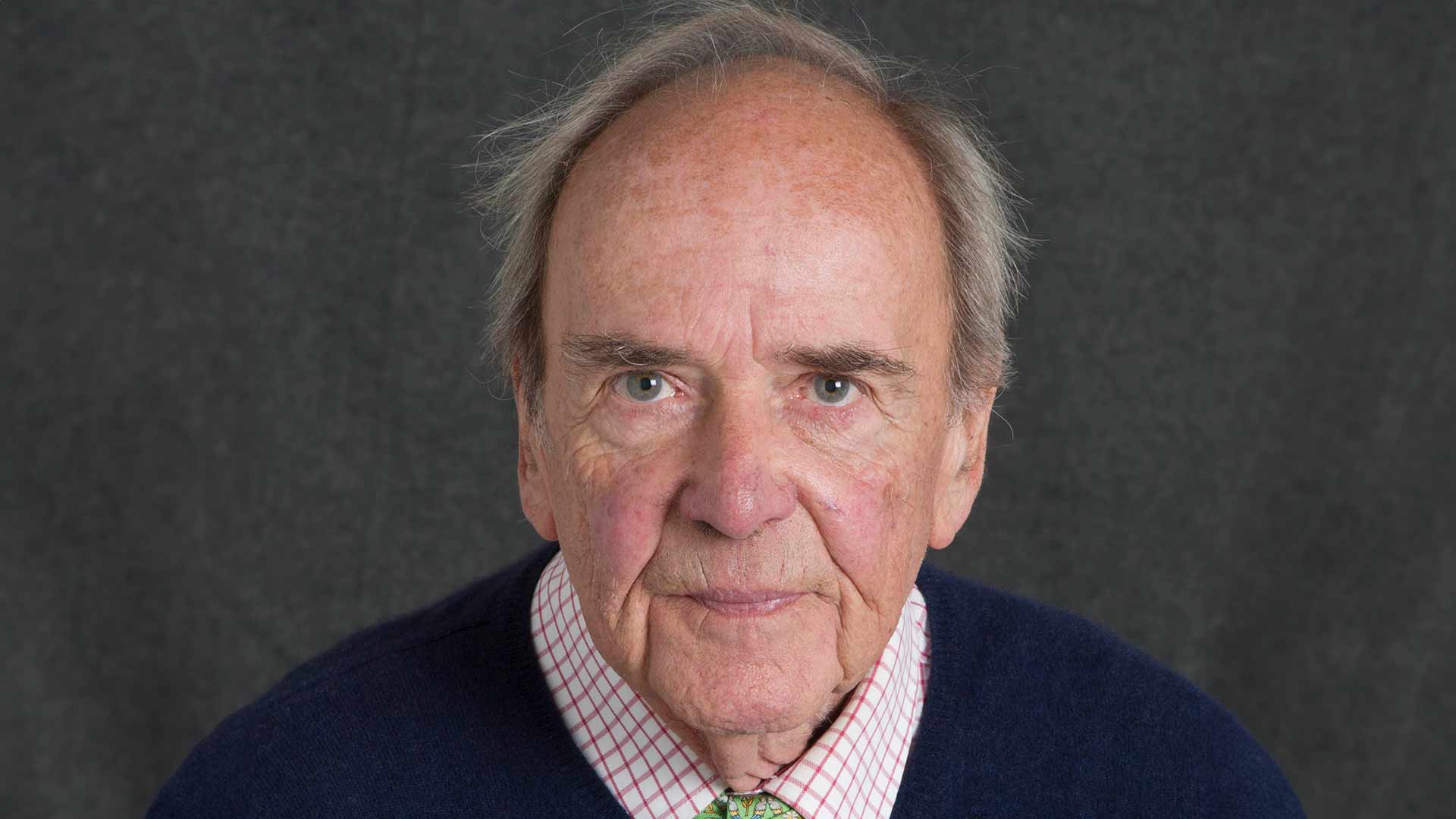

Anthony Cheetham on the books that shaped him

The veteran publishing fire-starter is back in the world of books, and believes there is still much to be achieved in the business, both by looking back and forwards.

I last interviewed Anthony Cheetham in 2018. At the end of the meeting he quipped that was probably his last ever interview with The Bookseller. At the time he was passing the Head of Zeus baton to his son Nic. Since then, the business has been sold to Bloomsbury, and Cheetham Snr – now 81 and packing a CBE – is back in The Bookseller in a new role: that of author.

Cheetham’s A Life in 50 Books is to be published by Head of Zeus in March 2025. It is a history of his beginnings and publishing life told through selected titles. Most, as you might expect, were published by him, but others were part of his early reading experience: “Books I read under the bedclothes,” he says. Of the choices, he continues, “these were the ones that gave me the greatest pleasure, or sold the most”.

It is a good, if eclectic, list. Starting with Homer’s Odyssey and ending with works by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins and the German historian Ernst Kantorowicz. Those he himself published include Dune, The Thorn Birds, A Suitable Boy, Meetings with Remarkable Trees and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo; some are books he wished he had published (Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time, which he narrowly missed out on); others are simply classics that left a mark on him (The Lord of the Rings, War and Peace). There are a few surprises: Timothy Lea’s Confessions of a Window Cleaner, Storm Island by Ken Follett, Alien, the adaptation of the famous film by Alan Dean Foster, and The Art of the Deal by US president Donald Trump (see extract below).

Cheetham has had a peripatetic career in publishing, beginning with the New English Library, then Sphere Books in 1969 and ending with Head of Zeus. In between, he has either run or founded companies such as Futura, Century (eventually subsumed into Random House), Orion, Quercus and Atlantic. In his telling, his career began because of his love of reading: “When I proudly told my father that I was now employed at a salary of £1,200 per annum, he was profoundly disappointed that I hadn’t chosen, as he had, a career as a public servant. I pointed out that they were actually paying me to read books.”

The book is as much about the work as it is about the reading. Like many entrepreneurs coming into books, he sought to re-write the rules. From Sphere, he was employed by The British Printing Corporation to launch a new paperback company, Futura, as part of MacDonald & Co. “We saw ourselves as the Camberwell Cowboys, unfettered by convention and free to roam where others feared to tread.” It was there that the Confessions series took hold, along with a Kung Fu Westerns series, the Ken Follett, and, perhaps less known, a book titled Rugby Songs (1967), described as a mildly pornographic miscellany of locker-room drinking songs.

After Futura, Cheetham launched Century Publishing with Gail Rebuck, with Maeve Binchy’s Light A Penny Candle the first book published. That became Century Hutchinson, with Cheetham promoted “overnight from boss of an entrepreneurial start-up to CEO of a leading publishing conglomerate”. Here he published the Trump book, Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway, the bestselling self-help manual by Susan Jeffers, and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War.

We can reinvent ourselves as luxury boutiques catering to a limited but well-heeled readership of fellow bibliophiles

Century Hutchinson was later acquired by Random House, with Cheetham briefly sharing the role of CEO with the late Simon Master, before he was dismissed by Random House US head Alberto Vitale (as it happens, the morning after his author Ben Okri won the Booker Prize for The Famished Road). He founded Orion later that same year, with A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth, and Jostein Gaarder’s Sophie’s World, being notables from that period. Here, as Cheetham recalls, he overplayed his hand. “We went too far and too fast. We published too many books across too many different imprints, missed our budget forecasts and ran out of cash.” Orion was eventually sold to Hachette.

Three more start-ups followed – Quercus, where he joined with Mark Smith as executive chairman – publishing the Stieg Larsson – before his relationship with Smith deteriorated, and he joined his son Nic at Atlantic to develop a new commercial imprint, Corvus, before that too soured and he left to set up Head of Zeus, again with Nic, in 2012.

In his version, the success was around the bestsellers – of which there were plenty – with the business side fun and challenging but always a secondary concern. At Random House he says he felt more like an “administrator of imprints, not a publisher”. “Everyone likes the idea of getting to the top. But if you are the top of one of those groups, you don’t do any publishing.” Today, he is admiring of David Shelley, CEO of Hachette, both in the UK and US, and his being able to do both roles. “He’s actually pretty good at both. It’s bloody difficult. You can’t focus on the things that turn you on, you have to look at the whole picture.”

He cites the late Sonny Mehta, Smith, Ravi Mirchandani (now at S&S), and S&S UK head Ian Chapman as pubishers he admires, alongside Shelley, and Bloomsbury founder CEO Nigel Newton for his fortitude (“he’s quite determined to be carried out in a box”).

I wonder if he is regretful that he never managed to carry a business forward as Newton has done. “I’ve never had a happy owership structure, except my own,” he says, adding that in terms of management his error was that he always “favoured [his] individual interests over the rest”. He is still suspicious of corporate ownership, questioning how well a creative business can fit within a structure focused on profit. Investors, he says, often have an expectation that isn’t seen by anyone else, and they discover “that perhaps they were the only ones who had that expectation”.

Of the future, he says books are losing their readers to the streaming platforms, with artificial intelligence an existential threat. But he writes: “Nonetheless, traditional publishers who love books for what they are will not disappear. We can reinvent ourselves as luxury boutiques catering to a limited but well-heeled readership of fellow bibliophiles.”

He is still true to this métier. Over lunch at his home in Oxfordshire, he enthuses over books, past and present, and still to be published, recommending a number of writers to me.

Cheetham has an extensive library of past publications, much of them housed separately in a converted barn adjacent to his main residence. He is already working on a follow-up to this book, charting the 50 (or so) titles that have most made an impact on the world. Not all will have been published by him, but that many will have been – and on imprints he founded – is testament to the fact that this life in books was anything but a disappointment.

Extract

The Art of the Deal by Donald Trump has earned a place in this memoir not for what it is but for what it wasn’t. Trump claims that he didn’t write it in the first place, that he’d never met the ghost writer, read the book, or approved what the ghost had written.

We published the book all the same, under the Century imprint, and invited Trump to visit the UK for the launch […] Trump’s book does raise an important question: what is the art of the deal in the publishing business? I’ve spent fifty years in search of the answers. Here is a set of the five virtues I would recommend as the keys to a successful career in publishing:

1. Curiosity: an omnivorous appetite to explore any book, outline or proposal that comes one’s way; fact or fiction, history, science or philosophy, science fiction, romance or detective story.

2. Empathy: the ability to judge whether the writer has the ability to engage the emotions of the reader.

3. Resilience: the strength to live with the knowledge that the great majority of books published are destined for a short shelf life and disappointing sales.

4. Audacity: the boldness to put all reservations aside and go for broke when the right one hoves into sight.

5. Optimism: the belief that, whatever happened yesterday, tomorrow will bring new and better opportunities.