You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

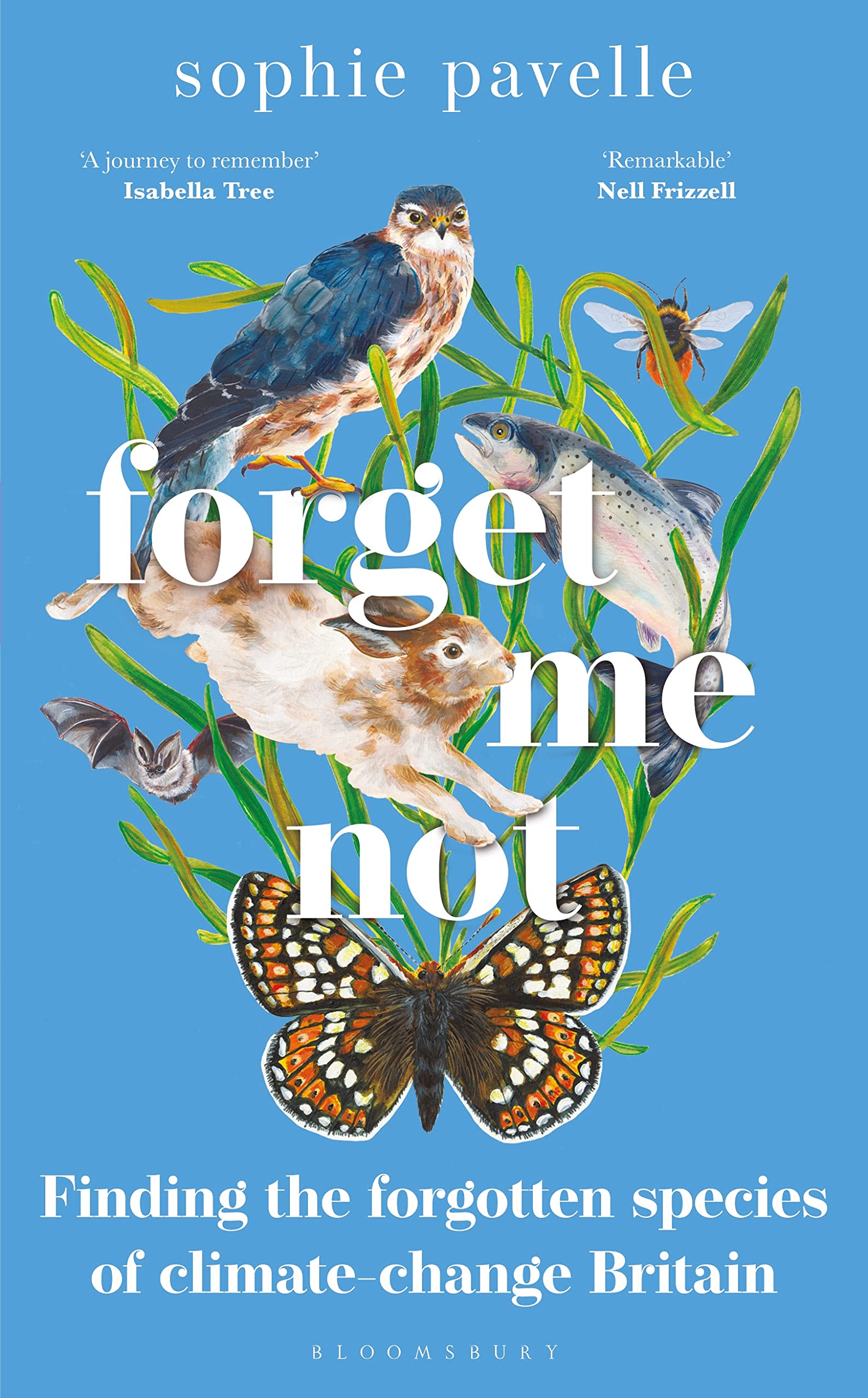

Sophie Pavelle on the climate crisis, endurance and resilience

Sophie Pavelle demonstrates that books on the climate crisis do not always have to be about doom and gloom.

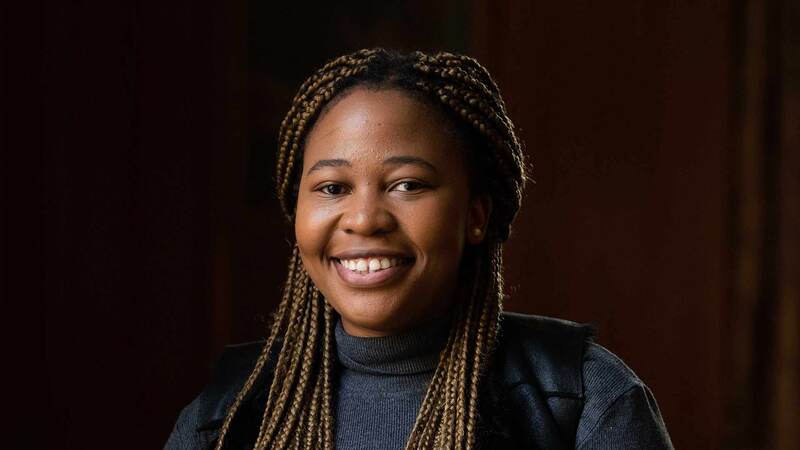

Spring feels like it has sprung when I meet Sophie Pavelle at a quayside outdoor café in her home town of Exeter. Unexpectedly springy, as I spend the good part of the interview regretting both the sunglasses and Ambre Solaire factor 50 left on the kitchen table; I later arrive back home with sunburn. In February. Ah, the curse of freckled Irish skin.

Pavelle arrives by bike, appropriately enough, as her book Forget Me Notis her low-carbon travelogue charting a trip during the pandemic to various parts of Britain, highlighting 10 species that have been threatened by the climate crisis. Pavelle spent much of those two Covid-blighted years journeying from Cornwall to the Orkneys talking to experts about the dangers facing native British flora (seagrass) and fauna (Bilberry bumblebees, mountain hares, Atlantic salmon). The result is a remarkable and fascinating book that manages to convey a wealth of facts about the daunting future of these species—and, by extension, us—with humour and a lightness of touch. There may be a sobering threat of extinction for these plants and animals, but Pavelle still manages to make it fun and engaging.

Our relationship with nature should be thought of like our relationships with a parent or a sibling—something that’s interconnected, complex, developing and really difficult to describe

While the 28-year-old is a zoologist by training she describes most of her work as being a science communicator (in fact, she also trained in this, having done a science communication masters). Pavelle has a portfolio career as a sort of budding British naturalist version of Neil deGrasse Tyson with her work as a social media influencer, nature writing journalist, public speaker and presenter sitting alongside her main nine to five, as the campaigns director for “nature restoration” charity Beaver Trust.

Pavelle says: “I like to say a science communicator is a translator—taking all the complex science, data and meaty stuff and then presenting it in packages that the public can understand. But it’s difficult because how do you take something as monumental as climate change or climate action—whatever the buzzword that is being batted around now—and really engage the average busy person who has little time on their hands and is worried about the cost-of-living crisis? Especially as some messaging around [green issues] can easily be seen as coming from someone on their high horse, and can be really counterproductive.”

So how can it be productive, then? “Our relationship with nature should be thought of like our relationships with a parent or a sibling—something that’s interconnected, complex, developing and really difficult to describe. Because I think only then when we have this emotional connection will we actually make time to address the problems.”

Outside of the mountain hare—with its saddening climate change problem that its coat still turns a previously camouflaging white in winter despite the paucity of snow in recent years—there are few traditional, heartstring-tugging, cutesy endangered animals. There is a sprightly chapter on dung beetles, for example, with Pavelle dragging her rather reluctant friend Gina along to inspect an important part of the insect’s breeding cycle: the great British cowpat. There begins a rather long paean to cow poo, because as Pavelle writes, “It is nature’s will that a successful shag [for the dung beetle] depends on the availability of good dung… Some ecologists observed up to 50 beetles arriving by land and air [to a pat] in less than 20 minutes of a cow having a dump. What a superb fleet of horny dung-miners!”

This was a concerted strategy, Pavelle explains: “I didn’t want any of the poster species of conservation: no puffins, no dolphins, no beavers. Because it was really important that I didn’t know anything about the species so that the reader and I are learning together, almost as friends. A lot of nature books I’ve read feel that the author is way up here, telling me what to think, how much they know and really showing off: ‘Look how much research I’ve done.’ Which obviously works for some writers. But I’ve found it is much more accessible to be learning together. Because then you and the reader are both surprised.”

One of the surprises for Pavelle in writing the book was that even though she was discovering frightening statistics about the difficulties facing these species, it got her thinking longer term. She explains: “These are monumental challenges. But we are so isolated in this short period of time where we’re alive, we indulge ourselves into thinking that the now is all that matters. But actually nature can be so resilient and has overcome so many roadblocks with extremes in temperature, ice ages, heatwaves… that said, it still frightens me. The Atlantic salmon, for example, has been unbelievably enduring. But in just a generation or so we’ve pushed them so far out into the sea that their navigation is being disturbed and they can’t get home to spawn. That we are able to disrupt such an ancient mechanism is terrifying.”

Born to run

Pavelle was born to naval officer parents in Augusta, Georgia, and was in America until her folks moved back home to the UK when she was four. She has spent much of her time since “on the banks of the River Exe” and her love of nature was partially instilled by her outdoorsy upbringing as she used to roam over Dartmoor and Devon’s South-West Coast Path. She considered a literature degree (“I’ve always been a writer”) before plumping for zoology at Bristol; her masters in science communication at the University of the West of England in many ways has allowed her to marry a love for the natural world and writing. She has been campaigning, writing and speaking ever since, joining the Beaver Trust in 2020, and is a youth ambassador for the Wildlife Trusts and on the advisory committee for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

She has been at the Beaver Trust at a pivotal time for the animal in the UK, with a number of reintroduction projects, and last October the Eurasian beaver was recognised by the government as both a “native” and a “protected” species. “Beavers are having a moment,” she nods enthusiastically. “They represent everything we should be prioritising in the UK conservation sector, and our climate response as a whole: determined, systemic disruption, a re-building of climate resilient ecosystems from the bottom-up, undeniable public appeal and charisma. Beavers also test the human capacity and readiness for change. They are the ultimate teacher of ecology and adaptation. We can learn so much from them.”

Extract

Nature has always been there. A lovely little addition to our lives when we want it. A sunset? Yes, please! A boat trip to see some whales? Count me in! A kingfisher flying past during a picnic? Hello! But nature is challenging us. Actually, planet Earth’s climate and biodiversity crisis removed the cushion from underneath us decades ago. Yet the strange thing is, we still don’t seem to have noticed.

As I write this in the summer of 2021, the past two weeks have been fraught with change. Germany, Belgium and Uganda are dealing with horrifying, deadly floods. North America is grappling with record-breaking temperatures for a second time this year. Siberia—reliably one of the coldest places on Earth—is battling unprecedented wildfires. Back here in the UK, the Met Office has issued its first-ever extreme heat warning and the government is proposing a new oil field in the North Sea. All this while one in every seven UK species is facing extinction. And global plastic is set to triple in 2040, with plastic items outnumbering fish by 2050. How far are we willing to push our planet before it’s too late to turn back?

Pavelle acknowledges the wider climate emergency discussion in the media (traditional and social) can be fraught. She wrestles with her thoughts on some of the more in-your-face protests of Extinction Rebellion or Just Stop Oil: “I have the utmost respect for those activists: these are incredible acts of bravery and self-sacrifice—and they did a lot for raising the profile of that discussion. But I wonder how sustainable shock tactics are. Those protests that made headlines: are we still talking about them? How beneficial were they in the long term? Maybe that is just not the way I would tell [the climate crisis] story. Maybe this is just me being naïve, but I think you can also talk about these issues with joy, humour, positivity—while still being science-led—and people will come on board.”