You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

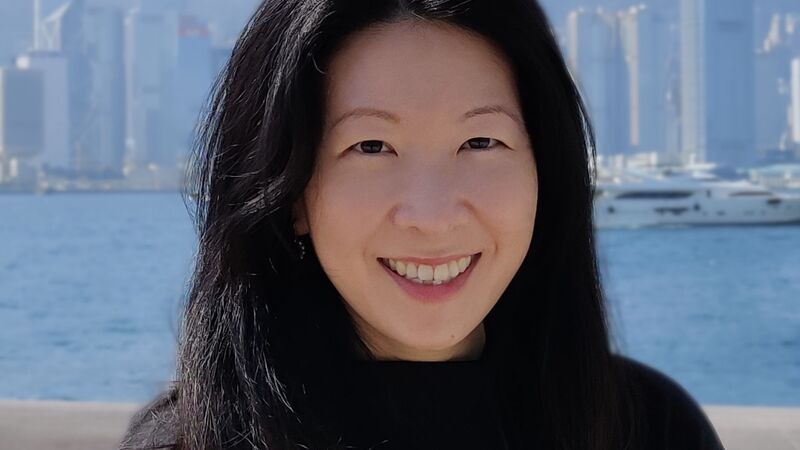

Beth Lincoln discusses her début children's book, a murder mystery with Gothic charm

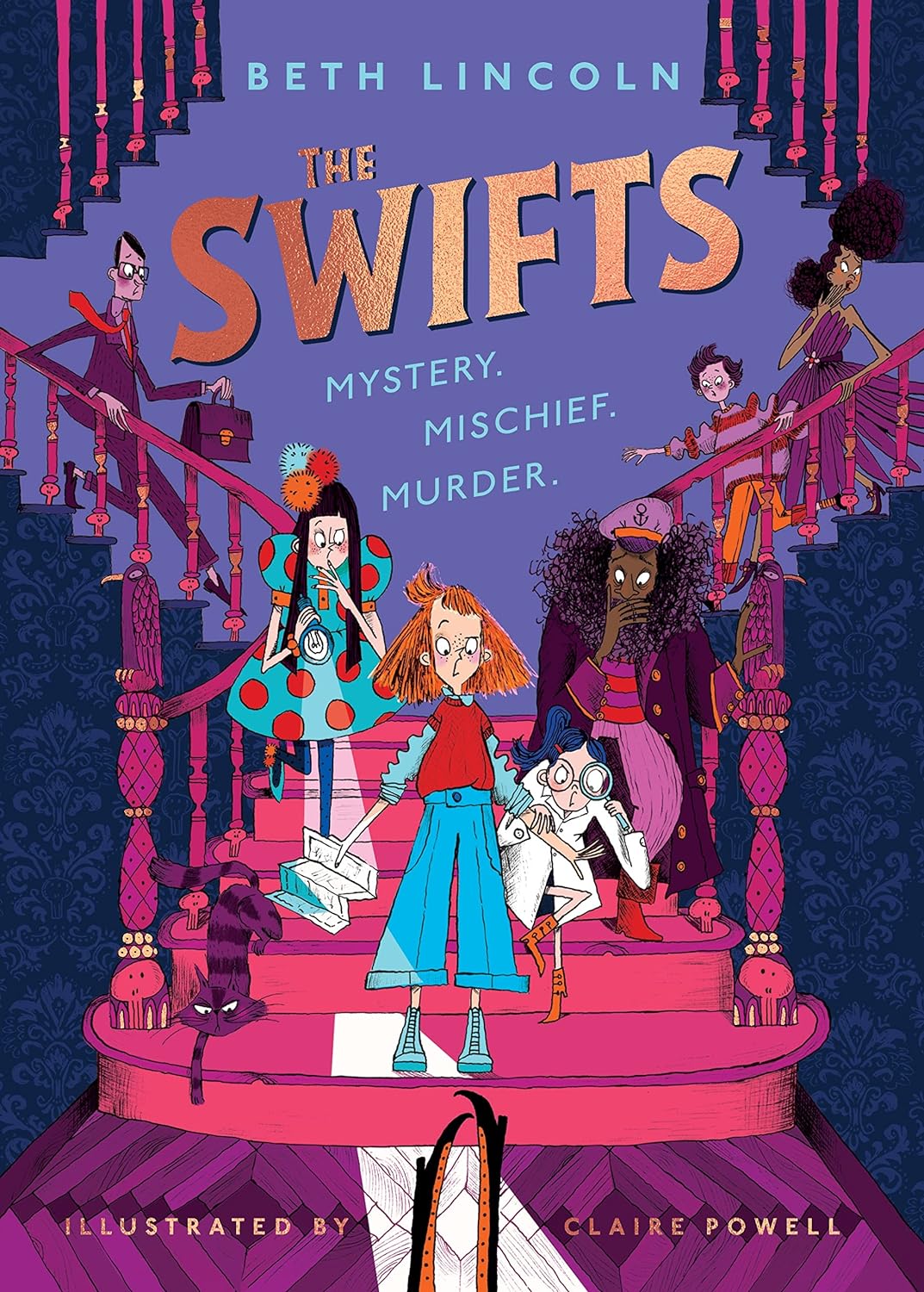

Murder mystery, Gothic charm and masterful wordplay converge in Beth Lincoln’s début children’s book, which follows a curious cast on the hunt for treasure.

In Beth Lincoln’s début children’s book, The Swifts, out in paperback in January, tradition dictates that on the day each Swift family member is born, the sacred family dictionary is consulted, and the child’s name selected at random. Superstition suggests that the child will grow up to match that name, a mixed fortune, perhaps, for those sporting such monikers as Atrocious, Finicky and Dither, but more fortuitous for the lovable and tenacious protagonist Shenanigan Swift. “Shenanigan is predicted to grow up to be a troublemaker and problem creator, which is pretty much true,” laughs Lincoln, speaking to me over the phone from her home in Newcastle.

In 2017, while studying an MA in Creative Writing, Lincoln was accepted on to Penguin Random House’s WriteNow scheme, a nationwide mentoring initiative to ensure PRH’s books and authors better reflect society. She began working on an early draft of The Swifts with editor Ben Horslen and the book was published in hardback early in 2023, featuring black and white illustrations by Claire Powell. Rave reviews poured in and, in America, the book won the prestigious Barnes and Noble Children’s Book Award, followed by 24 weeks on the New York Times bestseller lists. Puffin’s paperback publication in January will include two special sprayed-edge editions, one for Waterstones and another for independent bookshops. One of the standout débuts of the year, The Swifts is a joy to read. Described by one reviewer as “‘Knives Out’ by way of Lemony Snicket”, this expertly plotted murder mystery is steeped in Gothic charm, boasting a gloriously eccentric cast and fuelled by masterful wordplay. The dialogue is also a treat; Lincoln has an enviable knack for comedy, confessing that “what I find difficult is not making jokes all the time, the urge is so strong”.

I always knew that if I was going to write a kids’ book, it was going to be very queer

The Swifts follows a week in the life of Shenanigan and her siblings: Felicity, who bears the stigma of a boring name, and Phenomena, an aspiring scientist. They live in a huge rambling house (a formidable character in its own right, referred to as “the House”) with family matriarch Aunt Schadenfreude, Uncle Maelstrom and their guardian, Cook. Every few years the wider Swift clan gather for a reunion and to search for the lost treasure of terrible Grand Uncle Vile, believed to be hidden in the House. This year, Shenanigan is determined to find the treasure, until someone pushes Aunt Schadenfreude down the stairs and tries to kill her. Shenanigan’s focus shifts to tracking down the would-be murderer, assisted by her siblings and cousin Erf, navigating a chaos of family secrets, complicated loyalties and private agendas.

Lincoln’s lifelong love of language and etymology is woven into the fabric of The Swifts, an interest sparked by her Scottish grandfather who taught her snippets of Shakespeare, Ancient Greek and Latin and encouraged her to investigate the origin and meaning of words. Lincoln takes a similar approach at her school events, where she showcases intriguing and unusual words, like “curmudgeon”, and invites students to brainstorm their own new words. “It does a really good job,” she explains, “of illustrating to them what language can do and what language is for: expressing yourself in whatever way you can.” Themes of self-expression and identity are central to the novel: do characters live up to their names? How do they choose to present themselves to the rest of the world? It is most evident in the case of cousin Erf who is non-binary and chooses their own name in place of the one determined by the family dictionary, to the frustration of their grandmother.

That’s what inspires me, reading other writers who are being outspoken; looking at what’s available to children now and to keep pushing for that increase in diversity

“One of the reasons I was accepted on WriteNow is that I am a queer person,” Lincoln tells me. As a child she loved authors like Garth Nix, Diana Wynne Jones, Terry Pratchett and Lemony Snicket. But, growing older, she came to recognise the lack of representation across all fronts. “When you grow up queer,” she continues, “it’s very isolating, very lonely. For a lot of people, it’s a major lifeline to see representations of yourself in media. I always knew that if I was going to write a kids’ book, it was going to be very queer.” The majority of Lincoln’s main cast is queer, she reveals, something which will be explored more in subsequent books. She is keen, however, not to treat queerness as an issue. In the case of Erf, gender is part of their identity but not the focus of the plot. “The approach to language, to me, is inextricably linked to queerness,” she says, “because of that link between definitions and self-defining; being able to say ‘This is my sexuality, my gender expression, this is what is accurate and describes me’.” Lincoln speaks passionately about the importance of positive representation in children’s books and is encouraged by the improvements seen over the past few years. “That’s what inspires me, reading other writers who are being outspoken; looking at what’s available to children now and to keep pushing for that increase in diversity. To be more risky in what we publish.”

Extract

They halted before the grave, and there was a flurry of confusion as each Swift lowered the coffin at a different speed. Maelstrom tried to set his end down slowly, with dignity, but Felicity was a bit too fast, and Shenanigan was still thinking about being a faultress and not paying attention.

“Shenanigan,” Felicity hissed again, “can you please—”

The thing inside the coffin let out a yowl.

Felicity cried out and dropped her side. With a dull thunk, the head-end of the coffin hit the grass, teetered, and tipped over into the grave, the lid flying off as it went. Shenanigan leapt out of its path and straight into the black-frosted cake, her outstretched palms scooping up damp, vanilla-scented handfuls.

There was silence, but for the gramophone’s wheeze.

The Swifts peered cautiously into the grave.

The coffin lay wide open, revealing a gleam of black silk warming in the sun. Of course, there was no one in it—only John the Cat, who blinked sleepily, gave a luxuriant stretch, and trotted off in the direction of the woods. Shenanigan licked cake off her hands.

“Well,” called a voice behind them. “That was an appalling rehearsal, I must say.”

Lincoln is now a full-time writer, contracted to Puffin for a further three books. A Gallery of Rogues, due later in 2024, will see Felicity head to Paris to stay with estranged French cousins who are being targeted by a gang of thieves whose modus operandi is to steal art and return it to the original owners. How does it feel to reflect on her first year as a published writer, I ask? To achieve such success with her first book was, she admits, something she never anticipated. “It’s an incredible feeling but also terrifying to have your life change overnight.” Her favourite part has been meeting young readers. “Talking to the kids is so fun and so energising. What I hope is that kids come away from The Swifts confident in their ability to self-determine and express themselves.”