You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

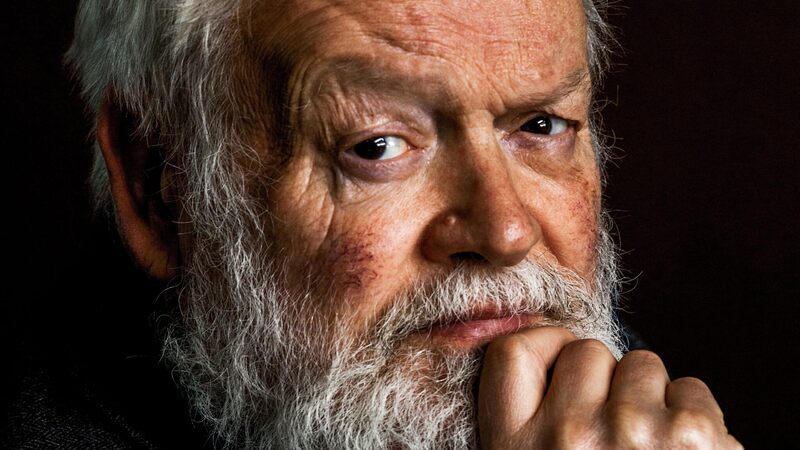

Booker Prize shortlistee David Szalay discusses his latest novel, which follows one man over the course of his life

Alice O'Keeffe

Alice O'KeeffeIn a nutshell, I read books for a living. I interview authors for The Bookseller's weekly Author Profile slot and write the monthly New T ...more

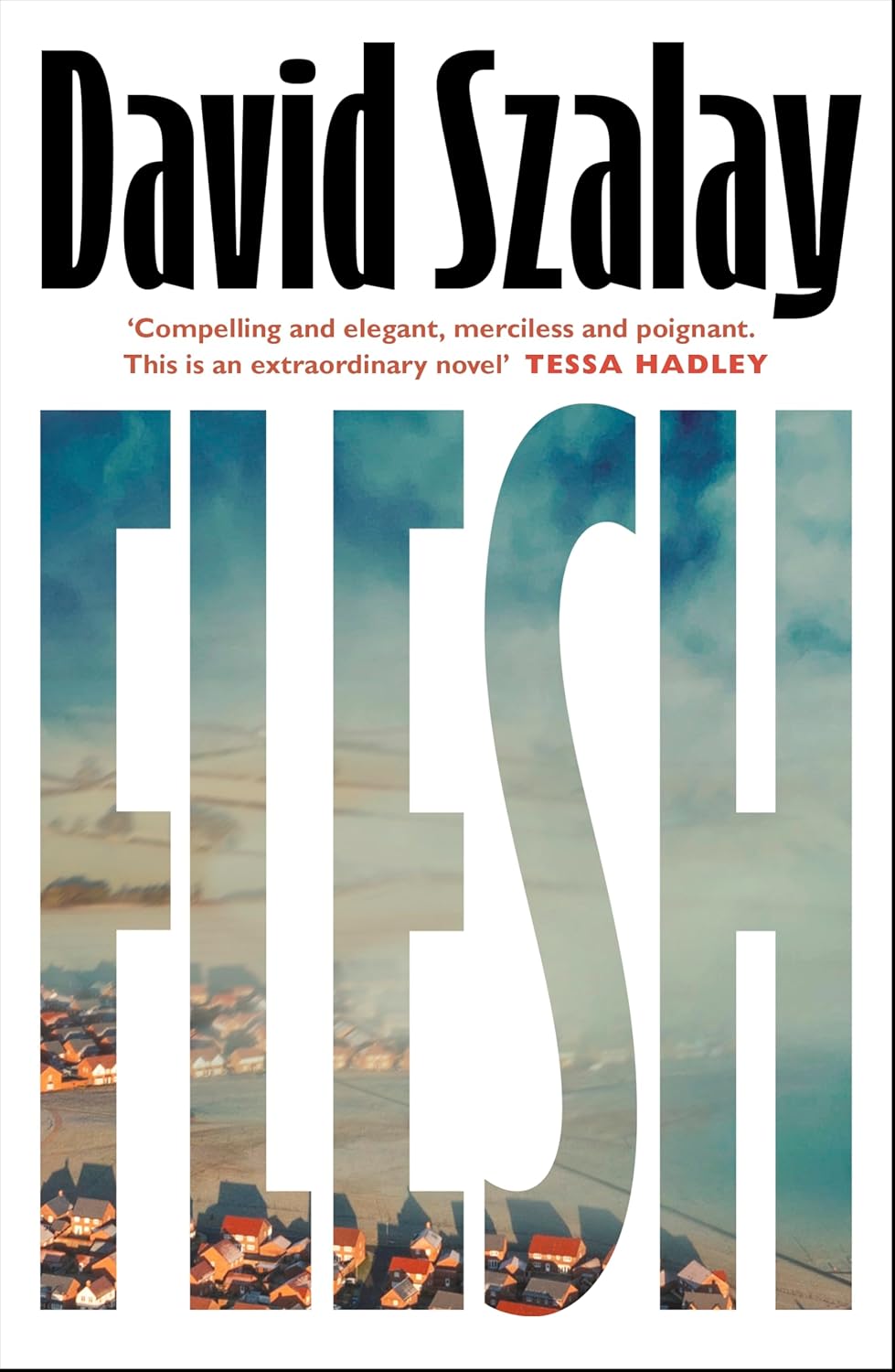

Flesh follows one man’s life from awkward Hungarian teen to the company of the international super-rich.

In a nutshell, I read books for a living. I interview authors for The Bookseller's weekly Author Profile slot and write the monthly New T ...more

“Books that lean into the short attention span of our era – I think that’s kind of inevitable. It’s almost a part of the craftsmanship, in a way.” David Szalay is reflecting on his love of the linked story structure, a feature of both his breakthrough novel, All That Man Is, and his latest, the phenomenal Flesh.

Szalay was chosen as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists in 2013, but it was All That Man Is, his fourth novel – shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2016 – that cemented him as a serious literary name. It provoked much debate at the time; with nine narratives from different men, was it a novel, or a collection of short stories? Over video call from Budapest, Szalay explains that he thinks of All That Man Is as “a novel hiding inside a story collection” and Flesh as the inverse: “a story collection hiding inside a novel”.

Flesh follows the life of a single protagonist, István, who we first meet as a 15-year-old boy, living with his mother in an apartment in 1980s Hungary. New to the town, he struggles socially at school and when a neighbour – an older, married woman – instigates a clandestine relationship, he goes along with it. The direct consequence of the affair is unexpected and shocking. It also sets the tone for the rest of the novel; István is someone to whom things happen, rarely the instigator, seemingly passive – but Flesh is never less than completely gripping.

Each subsequent chapter alights on another stage in István’s life, like a stone skimming over water, following him from awkward teenager well into his 60s. Each chapter also works, quite brilliantly, as a perfectly contained short story, able to stand alone as well as driving the novel to its tragic denouement. As the years pass, we follow István as he drifts into the Hungarian army and, later, like many Eastern Europeans, when he goes to seek his fortune in London, where a chance encounter propels him from Soho strip-club doorman to close protection work for the international super-rich. He travels further still, socially and economically, into a life he could barely have imagined.

There is something a bit tacky and tawdry about the title Flesh. I think that’s quite good in terms of conveying a certain aspect of the book

Throughout, István is a remarkably inarticulate protagonist, I suggest. At no point does he, in Szalay’s words, “directly unburden himself and explain his own psyche to the reader and to other characters in the novel”. Intriguingly, he says little, and we are not privy to his thoughts.

“I was very drawn to the idea of having a character who wasn’t articulate, who wasn’t able to tell the reader what the significance of his own story was, perhaps would be a way of putting it,” says Szalay. He’s not quite sure why he finds inarticulate characters so appealing – there are plenty in All That Man Is – but does think that “it makes the work of the writer more interesting because the character has to reveal themselves obliquely, somehow, and that oblique revelation, between the lines, can be more impactful [for the reader].”

Flesh, as the title strongly implies, is a novel concerned with “being a body in the world, and existence as a physical experience”. Rather than delve into the psychology of a particular individual, Szalay was more interested in “the way that our lives are in some ways determined by physical experiences as much as by mental choices”. He sees Flesh “as a tragedy, in a way”, and István “as a tragic hero”.

Interestingly, Flesh was Szalay’s working title and he fully expected “a more literary title” would be favoured by his publisher. He likes it: “It’s a good, impactful, strong, memorable title. But there is something also a bit tacky and tawdry about it. I think that’s quite good in terms of conveying a certain aspect of the book.”

Unfolding in taut, economical prose, Flesh also shows the impact of world events on the life of an individual – Hungary joining the European Union and the free movement of people across Europe, the Iraq War and the Covid-19 pandemic. Many of István’s more extreme experiences take place off the page and, when the reader meets him again, these experiences are subtly marked on him. He is changed by events beyond his control, even if he doesn’t talk about it.

What is not said is as important as what is. This aspect of the novel was something Szalay “gave a lot of attention to”, the sense of István “changing, but often in a way that is quite difficult to put your finger on”.

He says: “I’m pretty happy with the way that worked out. I guess that, by the end, he’s in some ways an unrecognisably different character from the character at the beginning of the book. But in other ways there is a continuity, and it does feel like the same person.”

Szalay was born in Montreal to a Canadian mother and a Hungarian father, but grew up in London, where the family moved for his father’s job. After reading English at Oxford, he worked briefly in the City in financial ad sales, which provided the inspiration for his 2008 debut – and perhaps most conventional – novel, London and the South-East, which won a Betty Trask Award. He moved to Hungary initially for one summer, to take advantage of an empty family flat in which to write, and ended up living there for 12 years with his wife and children.

I’m curious whether working in English, while living in a non-English speaking country, affects his writing. “I’ve thought about this myself, that there’s something very neutral about the language, particularly of Flesh, but also perhaps of Turbulence to some extent as well.”

Turbulence, the book he wrote before Flesh, was conceived as a series of 15-minute radio stories, commissioned by BBC Radio 4. Each story could be only 2,000 words, which forced Szalay to write in “a very, very concise way; I do feel that the habit of writing in this way carried over into [Flesh] as well.”

By the end of the novel, Flesh has looped elegantly back to its beginning. There is a pleasing circularity to it, also present in Szalay’s earlier books. He suggests this is because “the language that I’ve come to use as a writer is very pared down – unliterary or unshowy, perhaps quite simple – also because of the extreme naturalism that the books have in some ways, that makes the structure more important, in terms of making them feel like finished works.

“I imagine I’ll keep doing things like that in some way. I think a novel that’s a chunk of life probably isn’t something I can really imagine writing.”