Carol Atherton on her debut and how books transform how we see the world

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

In her debut book, English teacher Carol Atherton explains why books have such an impact on the way we see the world.

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

"One of my favourite descriptions of teaching talks about the teacher as being like a lightning conductor. As an English teacher, you are conducting the relationship between teenagers, the text and the world they are living in.”

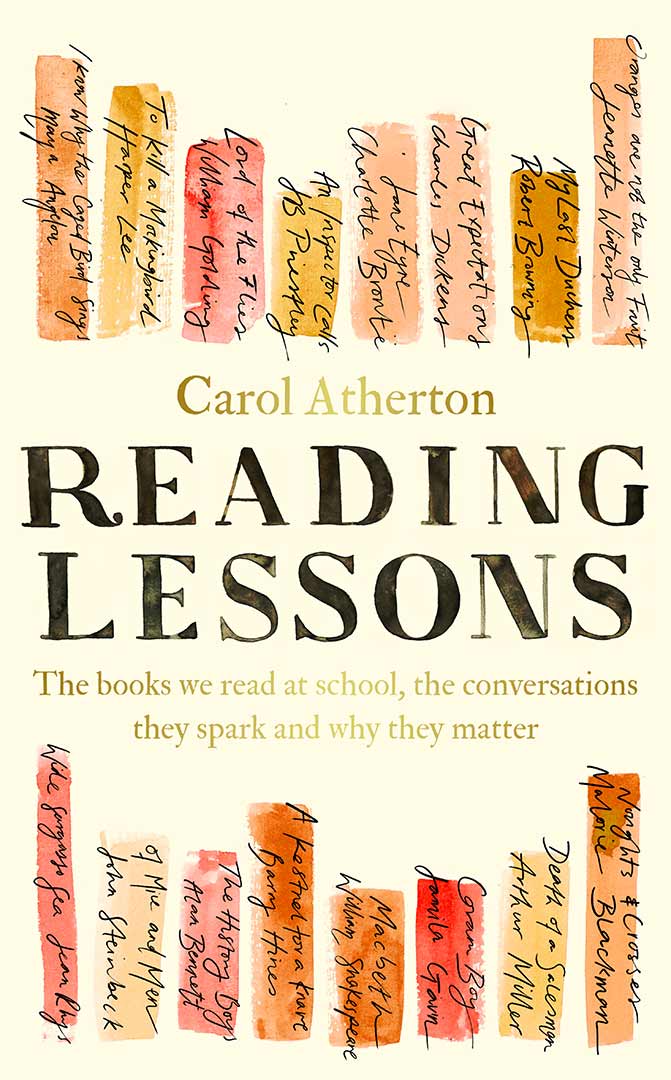

Via after-school video call from her home in Lincolnshire, Carol Atherton, head of English at a state boys’ grammar school, is talking about her first book, Reading Lessons: The Books We Read at School, the Conversations They Spark and Why They Matter. Revisiting 15 texts frequently encountered in the classroom, and drawing on her own three decades of teaching experience, she explores the enduring value of studying English Literature through works including Lord of the Flies (see extract), I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, and “Death of a Salesman”.

If you’re in your book trade job partly because you loved English at school, then Reading Lessons is certainly a book for you. But even if you didn’t care for Jane Eyre, you should still read Atherton’s book. Because while the relationship we have with the books we are compelled to study can be complicated (we might even loathe them), we encounter them at a crucial stage in our development when our identities are being formed. Books read at this stage of life, Atherton asserts, can spur us to look at the world in an entirely different way.

As an English teacher, you are conducting the relationship between teenagers, the text and the world they are living in

Indeed one of the strengths of Reading Lessons isn’t that it holds up classic books such as Of Mice and Men as totems in some rarefied canon of great literature. Rather it is about their latent power to speak to different generations and different cohorts of school students in diverse but equally relevant ways. Take the opening chapter entitled On Power, Gender and Control in which Atherton interrogates Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess”.

I remember my own lessons on this 19th-century work as being pretty dull. But Atherton uses the poem—about the relationship between a young woman and a man who thinks he should be able to dictate how she behaves—to discuss issues of coercive control and toxic masculinity which could not be more topical. “I try to prompt the boys I teach to think about it not just as a poem about something that happened in the Italian Renaissance but one that expresses certain attitudes and a desire for control that is so much part of our modern dialogue about gender and relationships.”

Complex lessons

Her chapter on To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee is entitled “On Complexity”. This is the book she remembers most clearly from her own GCSE studies (“I can’t imagine what my life would have been like without it”). But as a teacher she also gets students to think about the difficulties of studying a text which contains racist language and which some regard as promoting white saviourism, with its focus on Atticus Finch, “the good white liberal”.

What this kind of discussion can do for a student’s critical faculties is, argues Atherton, priceless. And essential. “About seven or eight years ago I taught a very bright young man who was never going to do English at A-Level—he was a scientist who wanted to do engineering at university. One day he said to me, ‘I’m really glad we have to do English Literature because it makes you think about things much harder than anything else we have to do’.”

Books extract: Reading Lessons: The Books We Read at School, the Conversations They Spark and Why They Matter

“’Why do we have to read this, Miss? I mean, what’s the point?”

The boy who speaks is blond and confident. He’s in the top set for everything except English, and he thinks he’s slumming it in my group… In his eyes I’m as low down the educational pecking order as it’s possible to be.

“Well, why? It’s not as though it’s going to get us a job or anything is it? We can all read and write already. It’s all pretty useless, if you ask me.”

There’s a whole raft of things I could say. I could tell him that English helps you read closely and look below the surface; that it introduces you to texts and ideas that will enrich you as a person. I could even point out that education isn’t just about getting a job….but I don’t think this is likely to convince him.

“We’re reading it because it’s an important novel. It tells us about human nature and how fragile civilisation is. What Golding’s telling us is that in extreme situations, society can break down. Once you scratch the surface, we’re all potential savages.”

“‘What, even you, Miss?”

There’s a laugh from the class. The boy smirks.

“Yes, even me. Now. Turn to Chapter One and let’s make a start.”

Commendably, Reading Lessons is also about books that have the potential to speak to students who do not have university in their sights. For example, while it is a book she has never herself taught, Atherton includes a chapter on A Kestrel for a Knave by Barry Hines. “I see so much in it about the way we still think about education for students who aren’t necessarily going to go on to further study. It made me realise how far we’ve still got to go in making vocational education a viable option for so many young people.”

While she isn’t overtly political in Reading Lessons, Atherton is critical of a current curriculum and of examinations that, she says, leave “little room for creativity”. She contests former Conservative education secretary Nadhim Zahawi’s view that literature taught in schools should be a collection of texts embodying some kind of set of eternal truths, to be handed down reverently from one generation to another. And she feels deep regret that the “relentless” emphasis on STEM subjects is leading to fewer students taking English at A-Level, at university, and training to teach it. “English deserves more than this,” she writes. “It teaches us to experiment and question, to read between the lines. We need these skills more than ever.”

Breaking the mould

Atherton, now in her early 50s, grew up in Merseyside and was the first in her family to go to university. When she won a place to study English Literature at Oxford her parents were proud of her but “had misgivings as to whether an English degree would lead to an actual career”. A spell working as a classroom assistant in a local primary school during a leave of absence year from Oxford convinced Atherton that teaching was the job for her.

English isn’t just teaching students about interpretations of a text. It’s about giving them the freedom to think creatively

Three decades on, it’s fascinating to listen to her talking both about teaching “Macbeth” (“a play about power and the desire for power”), and 21st-century texts such as Between Shades of Gray by Lithuanian-American writer Ruta Sepetys; which prompted one of her year nine students to talk to his own Lithuanian grandparents for the first time about the 1940 invasion of that country by Russia.

Towards the end of our interview, Atherton lets slip that following a call that morning from Ofsted, inspectors are arriving in school bright and early the following day. I offer my sympathies and hurry to finish our chat. What would she like her own book to spark in its readers? “I hope it sends them back to the books I write about and helps them realise why the discussions we have about them in school are so important. Back when I was training to be a teacher, it used to state in the National Curriculum that students should be encouraged to be ‘active makers of meaning and not passive receivers of meaning’. I’ve kept this in mind ever since. Because English isn’t just a matter of teaching students about interpretations of a text. It’s about giving them the freedom to think creatively.”