You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

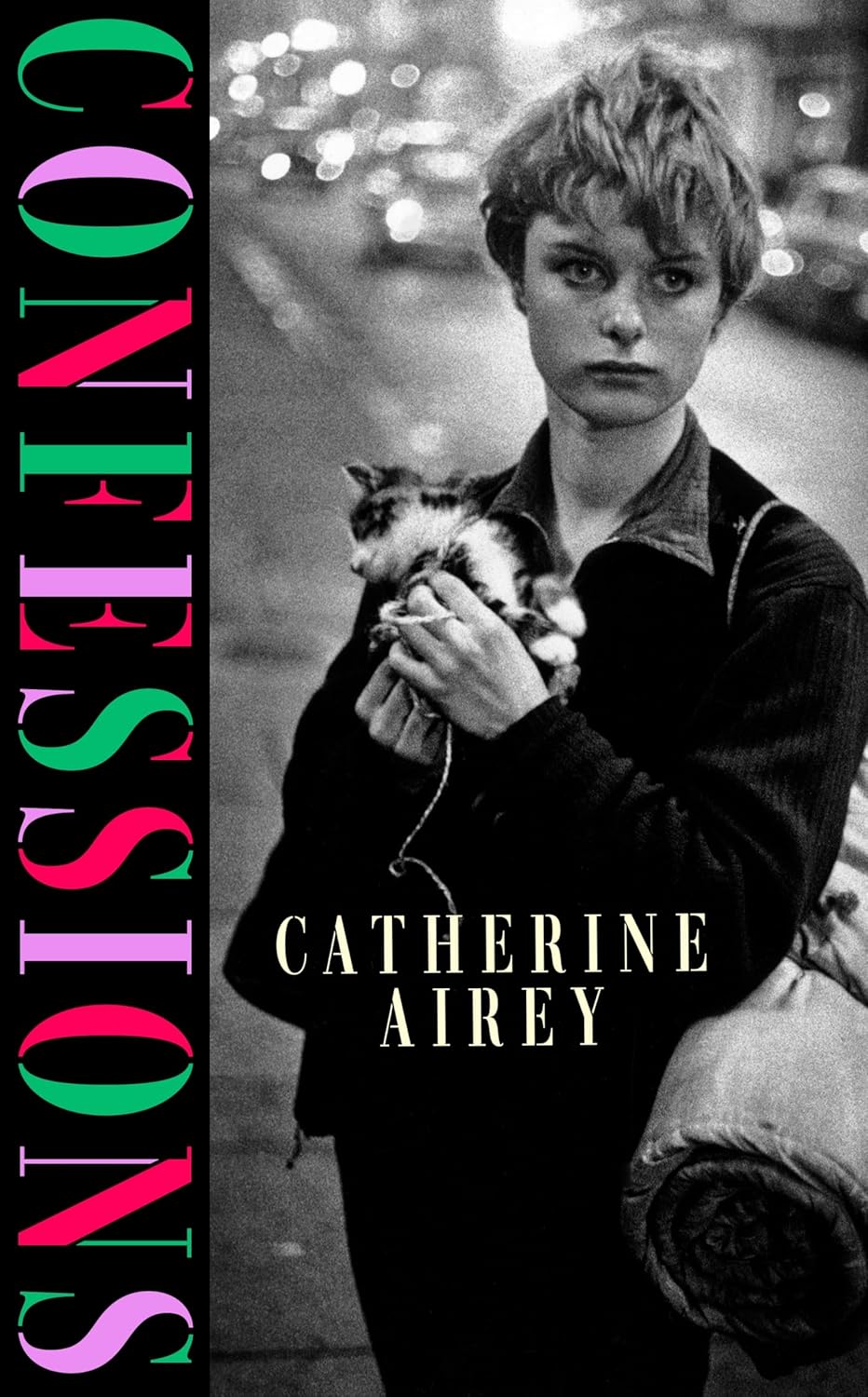

Catherine Airey’s sparkling début follows three generations of Irish women between Donegal and New York

Confessions is a multilayered novel spanning different eras and places, in an exploration of the trauma that comes with immigration

A number of authors have talked about how the pandemic lockdowns were beneficial to their work as they forced them to stay in and write. For Catherine Airey, lockdowns made her realise she needed to get out and write: out of her job in the civil service, out of London, out to go and tackle the novel she had inside of her.

So in 2021 the dual Irish/British national chucked it all in and with £3,000 in her bank account upped sticks to rural West Cork. She demurs when I say it was a brave move: “Well, I was going to where my grandmother was from and I had plenty of family about. And I didn’t really tell anyone I was leaving to write a novel; maybe it would have been braver if I had. But I quit my job, had gone through a bad break-up and was just running away from it all.”

To add flavour to the compelling author origin story, Airey was given a free place to stay in a friend of a friend’s house in exchange for her volunteering to help rebuild an old 50ft wooden boat (“I knew nothing about working on boats”). But that enabled her to write steadily and, just before her money ran out, came the stuff of every would-be author’s dreams: several agents bidding to sign her up when she sent the manuscript out—won by CAA’s John Ash. The book sold in a 24-hour, six-figure pre-empt to Isabel Wall at Viking (and later six figures at auction to HarperCollins US’ Mariner imprint). Announced at last year’s London Book Fair, Confessions will be Viking’s lead literary title when it publishes in January 2025.

A lot of books speed out of book fairs on the hype train. Some work, many do not: that is the nature of the beast. We will see next year how it does at the tills, but Confessions is an absolute triumph and deserves to be read widely, and should appear on débuts-of-the-year shout-outs and prize shortlistings.

The novel starts with a gut punch of a first few paragraphs, beginning with the Secret History-esque: “Two days after she disappeared most of my mother’s body washed up in Flushing Creek.” It moves along at a cracking pace throughout, all the more remarkable given that at its heart the book is an intergenerational Irish family saga.

It opens on the morning of 11th September 2001 with New York City teen Cora Brady, who has just dropped a tab of acid while she is skipping school and waiting for her drug-dealer boyfriend, learning that the planes have hit the Twin Towers—where her father works. The action flips between suddenly orphaned Cora drifting in the Big Apple and two sisters in Burtonport, Donegal—level-headed Róisín and kind but often cruel Máire Dooley—in the 1970s, who find themselves rivals on the cusp of adulthood, dealing with grief and buried family secrets.

Confessions is multilayered and complex. Not just in the narrative, but in the way it plays with the novel form, too, as it is polyphonic and written in different styles. A clever framing device is written as a choose-your-own-adventure text-based video game from the 1980s; this is not some contrivance but later becomes a central plot point. And while resolutely grounded in a gripping, very relatable family story, there are swings at some very big issues, as the novel takes in not just an era-shaping terrorist attack but rape, abortion, women’s rights and historic Irish institutional misogyny.

I was particularly drawn to the notion of primal scream therapy... I think it’s because it reflected the silencing of women everywhere else

Airey says in the writing that she was thinking less about those overarching themes, but that they were a by-product of exploring the trauma that can come with immigration: “I was very much inspired by my Irish grandma. She was amazing, brave, became a doctor, emigrated to London. Yet she had a lot of mental health and addiction issues. And there were these stories of when she moved over, especially during the Troubles, of not speaking to strangers to hide her accent. She once saw a man get beaten up on the Tube because he was reading the Irish Times. Immigration promises a better life, but assimilation isn’t easy.

“Then she would go back to Ireland and she didn’t fit in there anymore as she was seen as this remote doctor figure. You have this in a lot of Irish families, of course, this particular sort of loneliness of the immigrant, which I wanted to speak to.”

Much of the Burtonport section of the book is centred around a former school that is occupied by a primal therapy group, known locally as the Screamers, which is based upon the real-life Atlantis Commune that owned a house there in the 1970s. (Airey’s original title was Scream School, which had to be changed as a condition of the US deal.) After the commune dissolved in the early 1980s, the building was sold to the Silver Sisterhood, a matriarchal religious society that had a side hustle making text-based video games.

Airey mines both these stories in Confessions. She says: “I was particularly drawn to the notion of primal scream therapy. Not personally: I’m not screamy and shouty. But just in thinking of why women in particular were attracted to being able to scream and express themselves in these spaces. And I think it’s because it reflected the silencing of women everywhere else.”

Airey grew up in Potters Bar, in the house that her Irish grandmother bought after starting her medical practice in Hertfordshire. She says her household wasn’t particularly arty, but she always wanted to be an author: she’s kept a diary since age seven and one of her hobbies was taking novels and just copying them out word-for-word in her own notebooks. “Looking back, I think that actually might have been good training,” she says. “But I was always writing, though actually being a novelist never seemed like it was at all possible.”

After studying English at Cambridge, she got a job in rights at Penguin Random House Children’s: “I thought maybe being close to books would be the next best thing to being a writer, but actually being so near something I wanted to do so badly was worse. Also, I don’t think I was very good at selling rights.” That led to the civil service, writing copy and content for what she calls the “cool part” of the government. “It was actually lovely, if they hadn’t been so nice I might have started my novel sooner.”

Airey is currently working on book two, of which she does not want to reveal much except that “it will be more historical”. She is glad of the focus on the new novel, as publishing’s lead times have been oddly challenging. “Confessions still doesn’t feel real. I’m glad publication is closer, as for a while people would ask me what I do and I would say that I’ve written a book. And when they’d ask if they could buy it, I would say: ‘It’s coming out in two years.’ It has felt almost conceptual for a while, like I’ve just made it up in my head. But, I suppose in a way I have.”