You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Catriona Ward | 'It tested me more technically, and emotionally, than any book I’ve written'

The third novel from Catriona Ward, following two critically acclaimed literary horror titles, has received glowing reviews ahead of its release

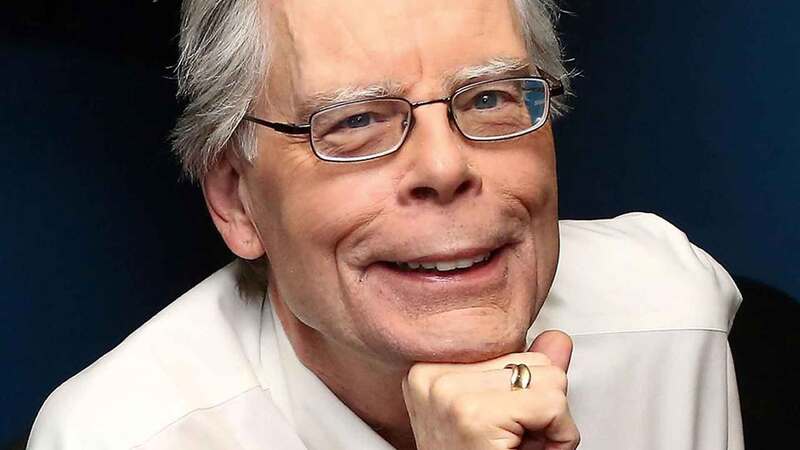

Catriona Ward’s third novel, The House on Needless Street (Viper Books), is fearsomely dark and magnificently multi-layered, a journey to the heart of trauma and abuse which comes emblazoned with a quote from the king of the horror genre, Stephen King: “I haven’t read anything this exciting since Gone Girl”.

It has its roots in a preoccupation of Ward’s: serial killers and their pets. Speaking via Zoom from Dartmoor, Ward gives as an example Dennis Nilsen’s dog Bleep, the only thing the multiple-murderer was concerned about after his arrest. “It’s someone who has no emotional affect, and is incapable of forming any meaningful relationships at all, and yet they can have this very close bond with an animal,” she says. “Thinking about it from the animal’s point of view, it becomes quite horrific, it becomes another form of captivity, because you’ve got this completely unknowing creature, having its own very powerful relationship with someone who, unbeknownst to them, is very dangerous.”

Her first attempt to write the book was in the voice of a cat, Olivia, owned by a serial killer, Ted. It didn’t work. “It was initially going to be all from Olivia’s point of view, so you would slowly figure out that there was something much darker that Ted seemed to be, kind of like [Henry James’] What Maisie Knew,” she says. Ward wrote a fair chunk in this way, but “decided I didn’t want to put all my faith in the novel in having an anthropomorphised talking cat. It wasn’t a broad enough canvas; it wasn’t telling enough of a story. It seemed to me that there was a much larger story to be told about trauma.”

Ward had already published two extremely well- received, though not huge-selling, literary horror novels. Her dazzlingly good début, Rawblood, a slice of Gothic in which a cursed family lives in an ancient house on Dartmoor, haunted by a bone-white woman, was released in 2015, followed by Little Eve, about a cult on a Scottish island in the 1920s, which won the British Fantasy and Shirley Jackson awards for best novel.

The House on Needless Street is very different. Contemporary, and set in the US, it is the story of Ted, who lives with his damaged daughter Lauren, and his cat Olivia, in the last house on Needless Street. He doesn’t let anyone into his boarded-up home, and he—one of several narrators in the novel—is confused, sometimes childlike. He remembers how a child disappeared and he was questioned by police. “Today is the anniversary of Little Girl With Popsicle. It happened by the lake, 11 years ago—she was there, and then she wasn’t.” He thinks of his mother: “She was born far away, Mommy, under a dark star.”

Dee, meanwhile, is searching for her sister, Laura, who disappeared years earlier. She’s out for revenge, and her search has brought her to Ted. Moving between the perspectives of Ted, Olivia (a gloriously vain realisation of a pet) and Dee, Ward has written a tremendously ambitious psychological horror novel, with panache. I’m not going to provide any spoilers, but it turned into something far darker, yet far more warm-hearted, than I was expecting.

“It’s probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done. It tested me more technically, and emotionally, than any book I’ve written,” admits Ward, who researched the mental health disorder at the heart of the book deeply. “I had a lot of unusual elements—a talking cat being one. And it felt very exciting. It felt like writing on a knife’s edge, really; I didn’t know for most of the book whether I could do it. That felt very dangerous, but also I just thought, ‘If I can do this, then hopefully it’ll be the best thing I’ve ever done.’”

Ward had just come to the end of a two-book deal with W&N, and was a little wary about showing her latest project to her agent, Jenny Savill at Andrew Nurnberg Associates. “I did think when I went into the meeting, ‘Is this an enticing idea for clients to come to you with? I’m just not sure,’” she says. “I said, ‘I’m going to write this book about a serial killer and a talking cat’, and she said, ‘Yeah, that sounds great’. Sometimes you need a tiny sign of encouragement, that you’re going the right way, that you might not be totally bonkers. Many people would have tried to dissuade me, or perhaps gently guide me into a slightly less uncanny and eerie territory, but [Savill] was very encouraging.”

Publishers didn’t at first get what Ward was trying to do; she and Savill had “rejection Mondays” where they would look over all the negative responses the novel got. Then they sent it to Miranda Jewess, at Serpent’s Tail’s new crime and thriller imprint Viper Books, and she “just got it immediately”. The dialogue around the novel changed when early proofs went out, and when King noticed what was being said about it and had a read.

An unusual route

Ward never set out to be a writer. After a peripatetic childhood—growing up in the US, Kenya, Madagascar, Yemen and Morocco—she studied English at Oxford, and then went to New York to train to be an actor. “It was just a disaster,” she says. “It is very difficult to be an actor, it just sort of breaks your heart every day. You’re spending so much of your life being rejected, and also I was terrible at auditioning. I just couldn’t do it.” She moved back to London, and got a job working for a human rights foundation, working on programmes relating to climate change and indigenous people. Writing speeches for the foundation and drafting articles got her thinking she wanted to write something of her own, so she applied to the creative writing masters at the University of East Anglia.

She knew the story she would be telling. The only continuity her travelling family had was the regular time they spent in a cottage on Dartmoor. Aged 13, she found herself waking every night with a hand in the small of her back, pushing her out of bed. “It was genuinely the most frightening thing I’ve ever felt,” she says. “It’s a different quality of fear, it’s a completely deep down, from-the-depths fear, there’s no place for it in the rational world.”

This happened four summers running. “We didn’t have Google back then, and there was no other explanation to me than it being a ghost,” she says. “Very late in my twenties, I talked to a professional and learned about hypnagogic hallucinations, which happen on the cusp of sleep. I still get them, but not at all as badly... I think if you know what they are, they’re much easier to deal with.”

She took from the hallucinations the memory of “bone- deep fear”, and when she began reading ghost stories and Gothic novels, she found a place for it. “I thought, ‘This is the architecture that contains that feeling’,” she says. “That was what made me feel this deep gravitational pull towards horror, the Gothic, the literature of the uncanny. It’s not just the idea of reproducing that fear, it’s about sharing it.”

For Ward, all good writing contains horror. “There’s always that little core of horror at the heart of human existence,” she says. “Writing that communicates horror is performing a deeply transactional act between reader and writer, whereby you’re making yourself very vulnerable as a writer. You’re saying, ‘I’m really afraid of this, and if you’re afraid of it too, then we’ll enter into it together.’”

This is something she takes seriously. “We’re not supposed to be afraid, really, as grown-ups,” she says. “It’s only children who are afraid of things in the dark and things under the bed, or that fear that doesn’t have any particular form—the shadows in the back of the cave. Horror is a way of us being able to engage with that fear as adults, and I don’t think as a genre it gets enough credit. It is a kind of healing thing, or at least the kind of horror I engage in. You walk through the darkness, but you come out the other side.”

Book extract

“Today is the anniversary of Little Girl With Popsicle. It happened by the lake, 11 years ago—she was there, and then she wasn’t. So it’s already a bad day when I discover that there is a Murderer among us.

Olivia lands heavily on my stomach first thing, making high- pitched sounds like clockwork. If there’s anything better than a cat on the bed, I don’t know about it. I fuss over her because when Lauren arrives later she will vanish. My daughter and my cat won’t be in the same room. ‘I’m up!’ I say. ‘It’s your turn to make breakfast.’ She looks at me with those yellow-green eyes then pads away. She finds a disc of sun, flings herself down and blinks in my direction. Cats don’t get jokes.”