You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Chris Mould talks about power and creativity in Orwell's Animal Farm

Charlotte Eyre

Charlotte EyreCharlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

Fresh from an acclaimed illustrated version of The Iron Man, Chris Mould tackles another classic story for Faber Children’s

Charlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

The very first text Chris Mould illustrated as a student was George Orwell’s allegorical novel Animal Farm. The young Mould was given Orwell’s text at art school and told to come up with 10 or so drawings. It seems fitting, then, that 30-odd years later Mould was commissioned by Faber to come up with a new version for today’s children and young people.

Orwell’s satire, originally published in 1945 by Secker and Warburg (ironically, T S Eliot at Faber turned it down), is about what happens when a dream of equality and fairness goes wrong: the animals at Manor Farm banish their owner with the aim of building a free and fair society, but utopia turns into a nightmare, and by the end of the book Napoleon—a pig—runs the farm as a despotic dictator.

Young people now have a whole feed coming through their phone all the time, not just politics, but music, fitness, a video of someone’s cat

Mould and Faber previously worked together on an illustrated version of Ted Hughes’ The Iron Man, for which Mould was shortlisted for the CILIP Kate Greenaway Medal, and the artist was keen to get involved when the publisher suggested Animal Farm could be their next collaboration. “It works on different levels,” he says. “If you look at what it is saying politically, it will always be relevant as a text, but from a child’s point of view it’s also about animals talking to each other, and that’s great fun.”

The story is known as (and was, in fact, written as) a criticism of Stalinism, but Mould reads the satire as being more about power generally. “If you remove politics completely and start all over again, you will always have people who assert themselves,” he says. “Things will level out in a way that makes politics unavoidable. You can decide you’re not going to have any political system at all, and it would always arise. That’s the thing I take from this. It’s about human instinct. How does politics arrive in the first place?” Readers can’t help but map the satire onto what is happening in the world around them, he says, and the story is “absolutely” relevant for children and teenagers in today’s “confusing” world. “When we were younger, we put on the news every now and then, but young people now have a whole feed coming through their phone all the time, not just politics, but music, fitness, a video of someone’s cat… It’s harder to tell what’s real nowadays.”

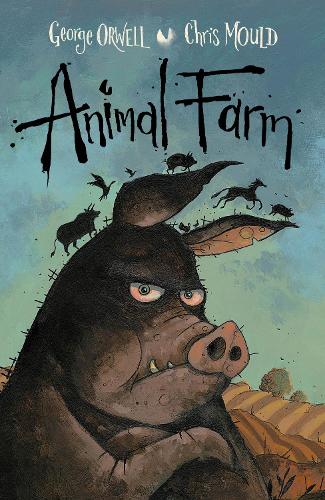

To illustrate the story, Mould used ink liners and brush pens to create black and white drawings, with a tint or wash applied over the top. Each chapter (there are 10 in total) has a double-page spread, a single-page illustration and a number of smaller spot illustrations.

Faber was keen for Mould to revisit the cartoon panel technique he used in The Iron Man, which he says is useful for showing progression. The illustrator reckons it worked well in Animal Farm’s fight scenes, and the tragic part of the story where Baxter, the old carthorse, is taken away to the knacker’s yard. Drawing animals was a relatively new departure for Mould, and the parameters he set himself were that they should not be too cartoony or overly anthropomorphised, and that each character should have a distinct look. Napoleon, for example, has tusks and a sinister face, to distinguish him from his main rival, Snowball.

I always find it interesting trying to come to come up with something new

Napoleon is the focus of the front cover, and Mould’s design shows the top of his head become a landscape, with the other characters running off the top. But the illustrator, who cites Ralph Steadman and Ronald Searle as artistic inspirations, says the horses were his favourite animals to draw. “They are such a challenge in terms of craftmanship,” he said. “There’s such a great history of equestrian art. The horse has been represented in so many ways, so I always find it interesting trying to come to come up with something new.”

Inspiring times

Mould left school at 16. The only thing he could do, he says, was draw, but books provided an escape from the nightmare of lessons; Mary Norton’s The Borrowers, C S Lewis’ Narnia series and Alf Prøysen’s Mrs Pepperpot stories were all firm favourites, and he loved the Beano and painters such as Pieter Bruegel. Mould didn’t, however, realise illustrating books could be a career. “I had an interest in that world and I always drew, but nobody told me where that could go. That’s why when I go to schools and festivals, I always like to pass that information on.”

He later went to art school (initially to study graphic design) and then to Leeds Polytechnic to do a degree in illustration. He got his first professional job by cold-calling Oxford University Press, saying he could hitch a lift with a friend and come to its office. The publisher agreed to take a look at his work and hired him to do some drawings for an anthology of scary stories, which led to a picture book deal. Mould worked for many years with the legendary Ron Heapy, and still has a relationship with OUP 30 years on, but he has also collaborated with Andersen Press, Bloomsbury, Canongate, Egmont, HarperCollins, Hodder, Macmillan, Nosy Crow, Orion and Penguin Random House. The list of authors he has paired up with includes Matt Haig, Lucy Coats and Barry Hutchison.

It’s a good thing to have to reinvent the wheel. We’re creatives. I’m sure we can think of something

Mould says he doesn’t know if he feels like a success. The sales of the Christmas books with Matt Haig and the Kate Greenaway shortlisting for The Iron Man were both highlights, but something he really enjoys is seeing the work schoolchildren create when they are drawing their own versions of the Iron Man. “Sometimes success is not about sales, but about how people embrace your work when you are out and about,” he says.

There is another book with Haig “knocking on the door”, as well as a picture book with Simon & Schuster. He’s also working on Jenni Spangler’s follow-up to The Vanishing Trick, a historical adventure story also published by Simon & Schuster.

Publishing Animal Farm during Covid-19 will be a challenge, but it’s not one Mould seems particularly worried about. “It’s exciting, in a way,” he says. “It’s a good thing to have to reinvent the wheel. We’re creatives. I’m sure we can think of something.”

One thing he hasn’t yet done, however, is have a look at the Animal Farm drawings he did as a student. “I probably have got those somewhere in my attic, hiding in a dusty old folder. It would be interesting

to see. Maybe I should get them down...”