You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Clive Myrie discusses his career, family and the Windrush Generation

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

The son of Windrush Generation parents, Clive Myrie examines what our nation owes to migrants from the Caribbean in a memoir of his life and BBC career.

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

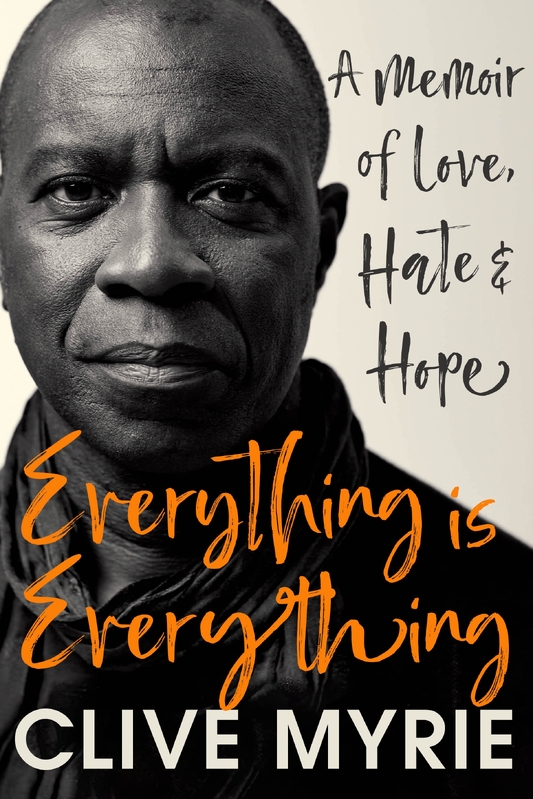

At the tender age of five, we learn in the opening chapters of his book, Everything is Everything: A Memoir of Love, Hate and Hope, the BBC’s Clive Myrie was so terrified on his first day at St Michael’s Church of England School in Bolton, that he threw up in the classroom. Almost 55 years later, he has—you might say—overcome his stage fright; in fact he arrives at our evening meeting straight from presenting the “BBC 6 O’Clock News” and still wearing his sharp, on-screen suit. He laughs when I mention his early introversion. “Yes, I was incredibly shy as a child, and at pre-school I was completely mute. But then I began talking and I haven’t shut up since.”

Given his sardine can of a schedule—reporting from Kyiv, hosting “Mastermind” and filming his series “Clive Myrie’s Italian Road Trip”, to name but three of his recent assignments—the fact that Myrie has found time to write a book is a shoehorning miracle.

In those days, the late 1980s, it was easy for someone else to define who you were going to be as a journalist

But the result—signed by Hodder in summer 2022—is an engrossing blend of the personal and professional, which sets his award-winning 30-year career as a journalist against the changing landscape of the country in which he was raised a Black Briton. “The original conceit for the book was a memoir that would chart the transformation of our nation in the period between one coronation and the next; which is also roughly the span of my life to date,” Myrie tells me. “But in the writing it became a love letter to the Windrush Generation.”

Generational shift

His own Windrush Generation parents migrated from Jamaica in the early 1960s. Myrie is the eldest of four children born after they came to the UK. The family was later completed by the arrival of his older sister, and two half-brothers—so-called “barrel children”—who at first remained in the Caribbean with their grandparents.

Myrie describes it as a “giant family where you really had to make your voice heard”. On his morning paper round as a teenager, he read all the newspapers from cover to cover—“like all good dealers I sampled my own product”, he quips—and dreamed of becoming a journalist. Television, his father’s “window on the world”, introduced Myrie to his early role models: the globe-trotting Alan Whicker and Trinidadian-British journalist Sir Trevor McDonald.

Building a new life in a strange land was far from plain sailing for his parents: as well as the hard graft and the racism, both stoically brushed under the carpet to this day, his qualified teacher mother had to shelve her dream of teaching in Britain for many years because of the expensive requirement to retrain; while his father never entirely acclimatised, or found fulfilling work here. I ask Myrie if he felt pressure to succeed given the sacrifices his parents had made. “Yes, I think I did. I knew what an effort my parents had made to ensure their kids had a good education. But because I understood why there was that pressure, it wasn’t an issue for me to want to try to achieve for them.”

Following a law degree at Sussex University, Myrie followed his heart into journalism and joined the BBC. From the outset he was determined to fight for options as a “journalist who just happens to be Black”. “In those days, the late 1980s, it was easy for someone else to define who you were going to be as a journalist. So I was fearful I’d get siphoned off into a Black ghetto of reporting and I really, really didn’t want that.”

The Windrush Generation was the beginning of the transformation of the psychology of white people in this country; and of a better understanding of minorities

After building his CV while insisting on being given the same opportunities as the white male journalists who dominated foreign reporting at that time, Myrie received his first full posting, to Tokyo, in 1996. Since then he has reported from over 90 countries, and been based in cities including Paris, Los Angeles, Singapore and Washington, DC, as well as London. In 2009, he came off the road as a full-time foreign correspondent to become a presenter and news anchor.

In time, Myrie began to cover the kind of Black stories he once eschewed, reporting on the historic US presidential election which sent Barack Obama to the White House; while his TV documentaries included one for “Panorama” about race in America in the wake of George Floyd’s death. A legacy of Myrie’s extensive reporting from across the pond is his perennial fascination with US politics and society. And yet his close-up observations of that country have convinced him that America remains a deeply riven country, with a still yawning disparity between the ideals enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the reality of life for so many. By contrast, he believes Britain to be the “greatest multicultural nation on earth”.

From the Covid-19 death toll to the murder of Stephen Lawrence, Myrie’s book makes clear he is no Pollyanna when it comes to modern Britain. He has himself been the victim of race hate crime, while his half-brothers and older sister were hounded by the Home Office to produce evidence of their right to reside in Britain during what has become known as the Windrush Scandal.

But in a narrative full of optimism he also credits the Windrush Generation with kick-starting the evolution of modern Britain, into a place far-removed from the one Enoch Powell once notoriously warned would foam “with much blood” if mass immigration from the Caribbean continued. “The Windrush Generation was the beginning of the transformation of the psychology of white people in this country; and of a better understanding of minorities,” maintains Myrie.

Inheriting ‘crown jewels’

Among those who congratulated him after he was given the job of presenting “Mastermind” in 2021, were comedian Jim Davidson (yes, really), and his fellow BBC journalist, George Alagiah, delighted that a person of colour had been given “one of the BBC’s crown jewels”. But it was after he anchored the news coverage following the death of Queen Elizabeth II last year—the passing of the sovereign whom his parents always admired and respected as their own—that Myrie’s undemonstrative father for the first time told his son he was proud of him, while his mother’s joy in his achievements has more often been in evidence; she particularly loved his relaxed incarnation as the presenter of “Clive Myrie’s Italian Road Trip”. Myrie hints at a second travel series, with the location yet to be revealed. “Alan Whicker here I come!” he laughs, before shooting out of the door to catch a train to somewhere else.