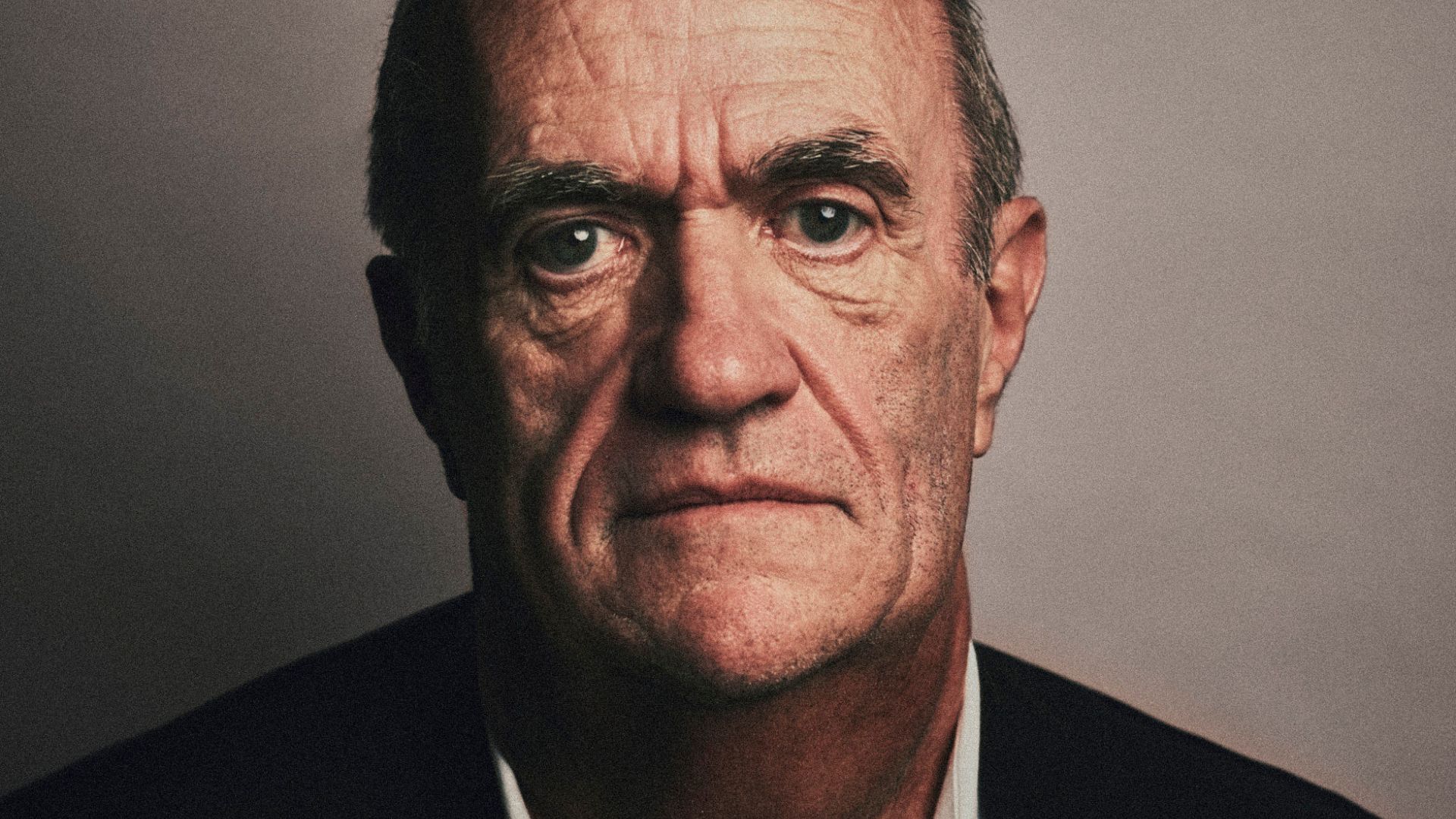

Colm Tóibín returns to the characters of Brooklyn in his anticipated sequel, Long Island

A familiar emigrant returns home in Long Island, Colm Tóibín’s sequel to the much-loved Brooklyn.

Long Island, Colm Tóibín’s sequel to his much-loved 2009 novel Brooklyn—later made into a film starring Saoirse Ronan and Domhnall Gleeson—opens with a bang. When last we encountered main character Eilis, in the final scenes of Brooklyn, she was preparing to return to 1950s New York and her new Italian-American husband Tony Fiorello, after a visit back to Ireland following her older sister’s death saw her unexpectedly fall in love with local barman Jim Farrell, only to be forced to leave again when the secret of her American marriage leaked.

Now, 20 years on, Eilis is a mother-of-two living with Tony and her Fiorello in-laws in a rather too-close-for-comfort housing cluster built for the extended family on Long Island. She does the books for a nearby garage business, supports her clever daughter’s plans for university, and has found ways to accommodate her own need for privacy with the demands of the family circle. But in the book’s first pages a bombshell is thrown into her life, and as a result Eilis finds herself heading back again to the small town of Enniscorthy where she grew up—and where Jim is still living, in charge of the same pub. While Tony waits in Long Island for Eilis’ return, Jim and Eilis are drawn together for a second time, and the unfinished business from Brooklyn is revived in a new configuration as complex as the first.

Tóibín, speaking via Zoom from the US, where he divides his time with his Dublin base, says he hadn’t imagined doing a sequel to Brooklyn, but that the opening scene occurred to him “out of the blue… I realised that was a story”.

“What is a plot in a novel?,” he asks. “An action that has consequences, which must not be predictable. I had an action that required consequences. I was thinking about something like the opening of Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge where he [the title character] puts his wife up for sale—well, what’s now going to happen!”

People read it as if it was an American book, it described what had happened to one of their ancestors, that a woman had arrived with a suitcase

Brooklyn has sold approaching 300,000 copies across print editions in the UK Total Consumer Market alone. Some of its great success with readers was unexpected, Tóibín explains. “In America it did something that I was very surprised by. People read it as if it was an American book, it described what had happened to one of their ancestors, that a woman had arrived with a suitcase—and that this was in their consciousness in a way that I had never really understood. That was the American part; the Irish part was, it’s the same story but the other way around—in every generation, every family lost someone, and they would use the word ‘lose’ about going to America. And in that sense it told a story that resonated hugely in Ireland and in America.

“But there was something else, I think, which was the mixture in Eilis—I was describing a younger sister in a relationship where the older sister is very powerful and makes all the decisions and is really very kind as well; when the younger sister [Eilis] operates almost as a pale star, and trying to capture that and also make clear that Eilis is also very intelligent. Some people thought she was too passive, but that’s essential, that she just drifts, goes with the flow.

“If you set out to try to attract a readership you would fail—at least I would, I wouldn’t know how to do it—I just followed the single idea that she was the younger sister of two and that she has always been protected and suddenly she’s not protected, and then we see how she functions in that way.”

The Eilis who returns to Enniscorthy in Long Island is something of a “ghost” in the town, as Tóibín describes it, after her two decades away: a half-outsider, quite glamorously American, yet unsure how to operate, what to wear, what to drive. She also has to endure her mother’s unspoken resentment at having been left alone when Eilis returned to New York that first time, breaking all the social codes of the time, that a widowed Irishwoman would never be expected to manage alone while she had a daughter living. Family—coercive, manipulative—doesn’t come off very well in Long Island, whether it’s the Irish or the Italian-American version.

What I was trying to get at, and I hesitate to use the word, was a sense of something slightly epic

But the attraction between Eilis and Jim revives. “The question was how to make [their contact] seem both casual and deliberate—that yes, he would see her on the street first and that moment would be enough,” muses Tóibín. “What I was trying to get at, and I hesitate to use the word, was a sense of something slightly epic. That moment when she leaves her mother’s house and he’s standing on the street smoking, that something in that gaze has more than just merely recognition; that both of them feel something and the reader gets that sense of how quickly she needs to get by him.

“The next encounter has to be closer but to say nothing: when he finally sees her, he says something really stupid like ‘Do you ever think about me?’—and then you need a big moment, at a gathering, and the only one you can really have is a wedding.” It’s at the marriage of the daughter of Nancy, another character who first appeared in Brooklyn, now widowed and running a chip shop, that Jim and Eilis make a decisive move.

Childhood pull

Elsewhere in his novels, Tóibín—the current Laureate for Irish Fiction—ranges widely across Europe and America, as in The Magician, his book exploring the life of writer Thomas Mann. Yet he chooses to return again and again in his novels to Enniscorthy, the very small town where Tóibín spent his own childhood.

He explains: “Everything that’s in Long Island exists in the town except Jim’s pub—all the streets are named, I don’t play with the topography. Three of my grandparents were born in the town—it’s a small place and because my father was a teacher and my sisters were teachers, we got to know the town at a certain level, where you got to know a lot of stuff about a lot of people. I’m not talking about scandal, but you could take people house by house, you could go to a wedding, go to a funeral and people would say, ‘Ah you’re so-and-so’s son or daughter home, you were in Australia’… I mean, the town has changed, a lot of Nigerian and Chinese and Polish people have come to live there, but it is very much locked in my memory up to a certain year.”

He thinks the town is “solidified by loss” in his imagination: “Enniscorthy was lost, because my father died when I was 12, the whole thing was gone. I went [away] to school at 15 and went there on holiday and weekends, and then just weekends, and that got fixed in my memory. And I can see it—the past that has a shape. I cannot put a shape on the present.”

As the characters in Long Island navigate their chances of happiness amid the often unforgiving rules of Enniscorthy society, the novel ends on an ambiguous note, and it is tempting to think the story of Eilis, Jim and Tony might not yet be truly over. Is there a chance that perhaps a further story could follow? Toibin will not be drawn by the suggestion. “I don’t know… I don’t know”, is all he will say.