You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Daniel Mason in conversation about discipline, style and the inspiration for his fourth novel

Pulitzer Prize finalist Daniel Mason discusses his disciplined approach to writing his fourth novel.

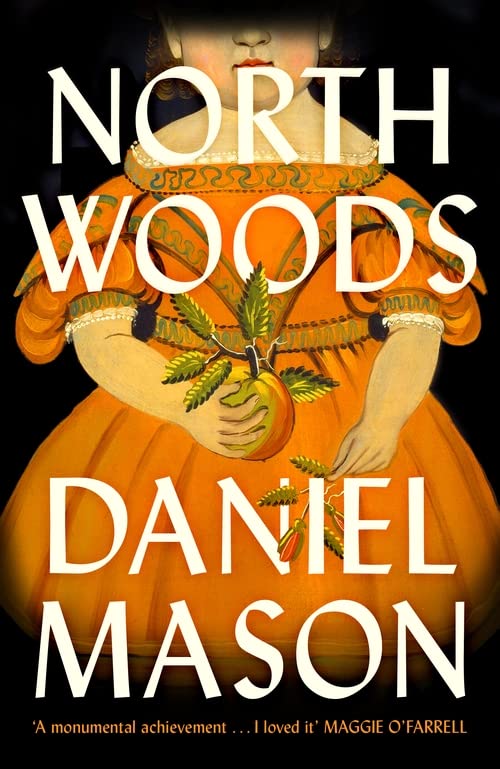

Daniel Mason’s virtuosic fourth novel, North Woods, is the story of a single house deep in the woods of New England. The first stone is laid in a clearing by a young man who has fled the established Puritan Colony with his lover, who was promised to a wife-beating minister twice her age. This house—first a simple homestead, a cabin built of log and stone by the pair of runaways—will stand for 400 years in one form or another, and this astonishing novel tells of those who inhabit it over the centuries, both human and animal, alive and spirit.

There is Charles Osgood, originally from Northamptonshire, an English soldier who came to America for war, before becoming obsessed with growing apples. In his search for the perfect apple tree, he finds the one that has grown from the apple eaten by a Puritan militiaman years earlier. Later, a pair of spinster twins grow older on the homestead, before one commits a horrific act. Later still, a merciless slave catcher tracks his quarry; a medium is summoned to deal with rowdy spirits; a crime reporter uncovers a sensational story; a mother worries about her son, who suffers from a mental illness; and a conman seizes an opportunity. Some characters linger on, past their own lifetimes, to return as spirits. Interwoven with the human lives that span the years are the non-human ones: a lusty beetle, a prowling catamount, a squirrel burying nuts that will one day grow into a forest.

There were times when [this book] absolutely felt like a chore, but much less so that my other books. It always felt like I wasn’t exactly sure what was going to happen and who was going to show and what the seasons would provide

When we meet at his publisher’s office, the softly-spoken author, who is visiting the UK from his home in northern California, explains that he wrote the novel over the course of a single year spent in Western Massachusetts on a Guggenheim Fellowship. “California is very unchanging. We have seasons but it’s nothing like New England, so it was just astonishing to arrive in a place that was so lush, so humid, the plants are so high—it was overwhelming.”

As well as being an award-winning author—his last book, A Registry of My Passage Upon the Earth, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize—Mason is also assistant professor in psychiatry at Stanford University and a practising physician.

Knowing he had a year to concentrate on writing, Mason began work in the summer and his first chapter, about the runaway lovers, was set in the heat of June. The second chapter, leaping forward in time and an account of a frontier raid, was set in July. He noticed the pattern and wondered if this might be the organising principle of the novel: “What happens if I just try to write in the season that the chapter takes place in, if I limit myself? Which was good for me also, I think, because I tend to take a really long time to write. My last book took 14 years, not because I wanted it to, that’s just what happened.”

A monthly process

He stuck to this discipline so each of the 12 sections of the book were written during the month in which it takes place. Sometimes he didn’t finish a chapter within the month and had to go back to it later in the editing process. Sometimes he finished it early and so would wait for the month to turn before beginning the next chapter. This process surely accounts for the gorgeously vivid way the natural world is described throughout the novel. “It was exciting, I didn’t know what was going to happen next, it was almost like reading myself. I was waiting and wondering, ‘What’s this season going to be like?’ Broadly I can imagine what it’s going to be like but I’ve no idea what colours are going to appear. It felt very fresh to me to be in that place.

If the book is ultimately on natural time, that’s the timescale we are looking at: the life of a single tree or a forest rather that the people in it who are dwarfed by that larger narrative

“There were times when [this book] absolutely felt like a chore, but much less so that my other books. It always felt like I wasn’t exactly sure what was going to happen and who was going to show and what the seasons would provide.”

The chapters of the novel may be anchored by month, but the exact year is never stated as the novel sweeps through the centuries. Mason has a “shadow file” he says, with all the dates but, and here he quotes the words of the apple-grower Charles Osgood in the novel: “I wanted to write a history of trees, not men.”

“If the book is ultimately on natural time, that’s the timescale we are looking at: the life of a single tree or a forest rather that the people in it who are dwarfed by that larger narrative. Tying things up with human dates felt like it did a disservice to the larger narrative, because those human dates aren’t the dates that really matter… the timescale is the timescale of the trees, the plants, the birds, the forest, and they are not interested in whether it’s 1776 or 1777.”

North Woods unfolds in a variety of styles. Some chapters are told in the close third-person narrative voice, but others Mason describes as “essentially found texts that the characters in the book experience”: letters, diary entries, songs, poems, even a pulp magazine article. He explains that, as he was reading about the history of a particular time, “I would come across these texts that were written in such wonderful language—which of course I’m not allowed to write [in], no-one would publish a book of songs written in an old style! But this is an excuse [for me] to use that kind of language.”

Mason’s inspiration

He particularly relished writing the letters from William Henry Teal, a painter, to a close friend: “Writing ornately about the natural world, which is very much the way I want to write about it, is very hard to do in a contemporary voice but it felt very natural to do in a 19th-century letter where there is this kind of unbridled indulgence.”

North Woods was influenced by Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse and two science fiction classics, Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles and Foundation by Isaac Asimov. Reading science fiction, he says, “it’s easy to be inspired because you don’t feel the anxiety of influence in the same way. It’s very intimidating to try and write something that’s inspired by Virginia Woolf… but to be inspired by Foundation when I’m not writing a science fiction book, there’s a lot of space for that. It’s not like that book is looming over my shoulder, watching what I’m doing. But that book also has these leaps forward in time with a total indifference to the lives of the [characters]. You really care about them, and then they are gone and that’s it. They are in the past.”

But, as North Woods shows us, the past is never really past—it stays with us, in the land we inherit and must protect. As Mason says of his novel: “I loved being able to channel what I was able to see around me and my astonishment at the beauty of it, into William Teal, the painter…he was a repository of what I would fall in love with when I went into the woods.”