You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

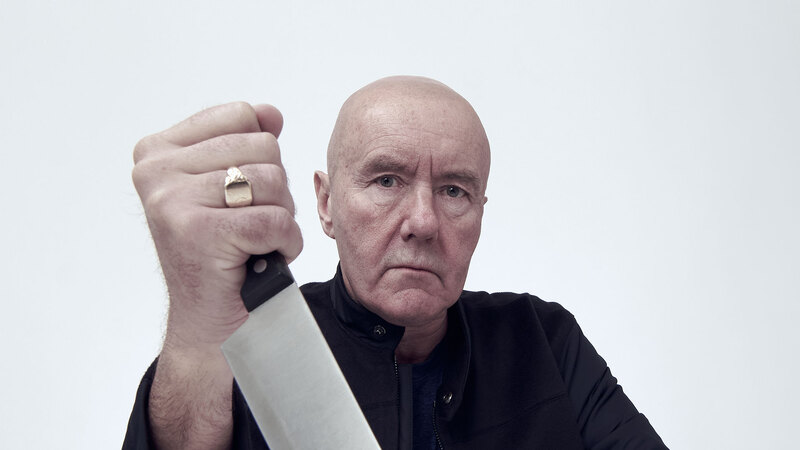

Dave Goulson | 'It’s hard to be overly optimistic, but there is hope'

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

In his latest book, biologist Dave Goulson makes the case for insects and how their loss poses a major threat to the future of the planet

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

"I have been fascinated by insects all my life. I’m not in any way religious, and I don’t believe in fate, but I do somehow feel that I was meant to write this book."

Dave Goulson, professor of biology at the University of Sussex and founder of the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, has already done a great deal to impress on us the importance of insect conservation through such engaging titles such as A Sting in the Tale and, most recently, the eminently practical Gardening for Bumblebees. But now comes the book that Cape describes as his magnum opus: Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse. It takes a panoramic look at the man-made causes of the frankly terrifying decline in insect species over the past half century, why it matters, and what we might do to reverse it before it’s too late. For in Goulson’s lifetime (he was born in 1965), insect populations have declined by at least 50%, and perhaps even 90%.

My approach is basically to tell people how bad things are, and then say, ‘but you can help make it better’. It’s hard to be overly optimistic, but there is hope.

Goulson’s love of insects goes back to his early child-hood in a Shropshire country village. When we speak via Zoom, I ask him what it was about them that so captivated him. “I think it was the fact that I could get really close to insects; that I could catch one and put it in a jam jar and watch it for as long as I wanted.” While his early passion was to dictate his career path as a biologist, he laments the fact in Silent Earth that he and his fellow ecologists and entomologists have done “a poor job of explaining the vital importance of insects to the general public”. So his book is, in part, his attempt to do better. “I’ve tried to explain why these little creatures are important—and what useful things they do: the recycling of cow pats and dead bodies, keeping the soil healthy, and pollination, which isn’t just done by bees, of course.” Each chapter in Silent Earth is prefaced by a short portrait of an extraordinary insect species: for example, Suicide Bomber Termites, The Pine Processionary Moth and The Earwig’s Second Penis.

While winning our hearts and minds for the insect cause is one purpose of Silent Earth (which concludes, as all of Goulson’s books do, with a galvanising section of practical actions we can all take to help repair biodiversity), averting the insect apocalypse is going to take a lot more than such admittedly positive community actions as leaving roadside verges unmown, creating more allotments and growing garden plants attractive to pollinators. This much is clear as Goulson sets out the likely causes of insect decline; from global warming, atmospheric and light pollution, and the increasing fragmentation of wildlife habitats due to human urbanisation; to modern monocultural farming practices and the widespread use of pesticides. In fact, global food production is now an area of increasing focus for Goulson. “One of the biggest challenges we face is: how to feed everyone without destroying the planet? Industrial-scale agriculture is not sustainable. It contributes about a third of all greenhouse-gas emissions, and is the biggest driver of biodiversity loss globally. And a third of the food we produce is wasted! It’s overly simplistic, obviously, but if we could do away with that waste, we could take a third of all the agricultural land in the world and turn it into a nature reserve. That’s an area the size of North America.”

Time for change

Silent Earth—its title both a lament for the decline in the sweet summer music of bees buzzing and grasshoppers chirping, as well as a nod to Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s early environmental warning (1962)—is an ambitious, even visionary book which uses the state of our insect populations as a marker for a whole catalogue of biodiversity decline that “most of us have not noticed”. Despite all the compelling evidence that has been marshalled by scientists over the past several decades, some of it by Goulson himself, he sees scant evidence of any political will to bring about change. “Politicians generally don’t seem bothered about the state of the environment: biodiversity loss, over-fishing, deforestation, soil erosion, and so on, are barely ever mentioned. And yet if we end up in a world where all the soil is washed into the sea, where there are no fish left, where there are no insects to pollinate crops, it’s going to be a complete disaster for everyone.”

Just as Greta Thunberg has said “I don’t want you to be hopeful, I want you to panic,” Goulson believes that shock tactics have their place. Indeed in a chapter entitled “A View from the Future”, he imagines the future deprivations of an elderly human in the 2080s, looking back nostalgically to a time when food was plentiful, and mourning the global inaction which failed to prevent the devastating floods of the 2030s, the terrible droughts of the 2040s and the empty seas of the 2050s. “My approach is basically to tell people how bad things are, and then say, ‘but you can help make it better’. It’s hard to be overly optimistic, but there is hope. Young people in particular are deeply concerned about what we’re doing and are committed to change, both on a personal level and a political level.”

One of the most striking revelations in Silent Earth is that the UK, famed as a nation of nature lovers—with our much-trumpeted National Parks and Sites of Special Scientific Interest, and millions signed up to conservation organisations such as the RSPB and local Wildlife Trusts—ranks so despicably poorly when it comes to biodiversity. A recent major global study which examined patterns of change in the abundance and diversity of 39,000 plant and animal species, across 18,600 sites globally, ranked the UK 189th out of the 218 countries included in the study, making ours one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world.

A new dawn

I ask Goulson if he believes the pandemic has in any useful way served to focus our minds on the challenge we face. “The negative side of it, I fear, is that governments around the world are now so in debt that they’ll drive ahead to grow their economies in any way they can. There’s talk of the ‘green recovery’ but I haven’t seen much sign of it. On the positive side however, there has definitely been an awakening of interest in nature, and more people have started to grow their own food, which has got to be a good thing. But what the pandemic really should teach us is that we can profoundly change and adapt. If you’d have said two years ago: we must stop flying because it’s really bad for the environment, you’d have been laughed at. But then suddenly we all stopped flying.

It wasn’t actually impossible at all, it just required us to have the will to do it. It shows that society can profoundly change and adapt, and that we can do things differently if we really want to.” And crucially, in Goulson’s dream world, “humans do not regard their own needs as having priority over all others”.

Goulson tells me about the two-acre garden he tends at home in Sussex. “It’s a slightly untidy mess, full of wild and ornamental flowers. I’ve got a great big veggie patch and a fruit cage and some chickens: we try and produce as much food as we can, in an environmentally friendly way. We’re very lucky, and in some respects I can’t wait to retire and just potter around the garden. But I’m afraid I’ve got to somehow help save the world first”.

Book extract

The sight of the first brimstone butterfly of the year, a flash of golden yellow wings on the first warm day in late winter, brings joy to my heart. Similarly, the chirrup of bush crickets on a summer’s eve, or the sound of clumsy bumblebees buzzing among the flowers, or the sight of a painted lady butterfly basking in the spring sunshine after her long migration from the Mediterranean—they all soothe my soul. I cannot imagine how desolate the world would be without them. These little marvels remind me what a wonderful and fascinating world we have inherited. Are we really willing to condemn our grandchildren to live in a world where such delights are denied them?