You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

David Whitehouse talks about his non-fiction debut

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

David Whitehouse’s About a Son is a stunning take on the true crime genre with a tragic death at its heart

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

On Halloween night in 2015, Morgan Hehir was out with friends in his home town of Nuneaton when they were attacked by a group of strangers. Hehir was stabbed in the heart and lungs and died hours later. He was 20 years old and worked in the local hospital, a talented graffiti artist who dreamed of building a life by the sea.

We stood on the spot where Morgan was murdered; we walked his last steps; we went to his grave. It was an immediately powerful experience to stand with Morgan’s dad on the very spot where he collapsed

In the immediate aftermath of Hehir’s murder, his father Colin began writing a diary, charting his family’s evolving grief, the eventual murder trial and his personal fight to expose the shocking fact that a young man with a history of violence was at liberty to take his son’s life. It was reading this testament which led novelist and screenwriter David Whitehouse—who is also from Nuneaton—to use it, with the blessing of Morgan’s family, as the foundation for About a Son: A Murder and A Father’s Search for Truth (Phoenix). A riveting blend of reportage, memoir and true crime, and the first non-fiction book from Francesca Main’s new Phoenix imprint at Orion, it is one of those titles that excels by defying categorisation. And yet if ever a book brought home the stark human reality behind the words “true” and “crime”, it is this one.

In January 2020, Whitehouse received an email from Claire Harrison, a reporter he knew on the Nuneaton News. She had covered Morgan’s murder and his father’s search for the truth about the individual and systematic failures that led to his son’s death. Colin had recently sent her the diary, hoping to get an opinion on it. She in turn sent the 100-page document to Whitehouse. “You can spend two years writing a novel, trying to get to the emotional truth of a character and you can fail, as I have in the past”, Whitehouse tells me when we meet at his publisher’s offices. “This unique document was so open, it was like looking into a well of truth. But I didn’t feel qualified to tell a man what to do with his grief. So it just sat on my desktop.”

Three months later, Colin got in touch with Whitehouse directly to ask what he thought of the diary. “He didn’t have any objective in mind other than having Morgan’s story told somehow.” The two then spoke on the phone for an hour. “The next day I called him back and said: ‘I have an idea if you’d let me explore it’. And Colin immediately said yes. He put complete faith in me and gave me artistic licence to do whatever I wanted.”

Whitehouse’s idea was to try and tell Morgan’s story by putting the reader in his father’s shoes. “It sounds a bit lofty but I also wanted to somehow translate the pain and loss from his personal experience into a universal one; to tell Colin’s story, but also the story of his family and the town, which I think is so important in understanding what happened to Morgan.” Whitehouse rewrote the first entry in the diary, and sent it to Colin, who gave him permission to continue. Over the following months, the two texted and spoke regularly on the phone, and from these conversations Whitehouse was able to add further colour to the story.

A story in three parts

Divided into three parts—"Loss", "Justice" and "Truth"—About a Son is exceptional, and not just because its beating heart derives from the vivid testament of a man who had “never written anything longer than a shopping list”. It is also outstanding for the way in which Whitehouse, as a professional writer, has used his craft—including an instinctive and brilliant use of the second-person voice—to write something seamless, where it is impossible to tell where Colin’s voice ends and Whitehouse’s begins. A more conventional approach might have been to ghost or co-write the book as a first-person memoir by Colin. I ask Whitehouse if this was ever on the cards. “There is a version of this book that is exactly that. But we always wanted to make it something other than a straightforward, conventional telling of the story. I never met Morgan but I wanted About a Son to reflect him in the way that another kind of book wouldn’t.”

The fact that Whitehouse is himself from Nuneaton adds to the book’s startling veracity. While writing it, Whitehouse returned to the town to spend time with Colin Hehir and his family. “We stood on the spot where Morgan was murdered; we walked his last steps; we went to his grave. It was an immediately powerful experience to stand with Morgan’s dad on the very spot where he collapsed, and it was all the more potent because even though I left the town a long time ago, I knew that exact place.”

I ask Whitehouse what his hopes are for the book once it is published. “The sole objective is for people to know Morgan’s story. The whole book turns on the moment where Colin and his family leave the trial, not feeling that justice has been properly served. And unlike what people imagine from watching TV dramas, there was nobody waiting to hear their story: no microphones, no satellite van, nothing. Every day, these things happen to ordinary, normal people but their stories are rarely told.” Morgan’s story, now optioned for television by Tannadice Pictures, is both emblematic of the tragedy of rising knife crime and an indictment of underfunded police forces and underresourced institutions operating in times of austerity. “That’s what these things looks like. They look like Morgan,” says Whitehouse.

You might baulk at reading such a dark story. But despite its grim subject matter, there are moments of sunny levity. A week after Morgan’s murder, the family decide to light and launch some Chinese lanterns from their garden in his memory. But the lanterns crash to the ground and set fire to the grass, and suddenly everyone starts laughing because they know Morgan would have found it funny too.

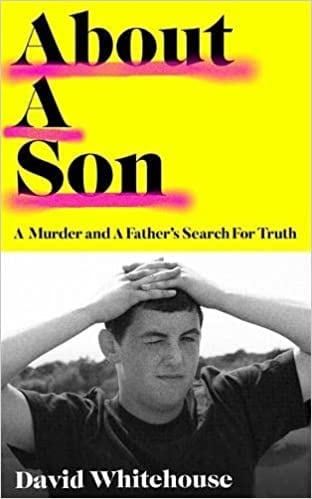

I tell Whitehouse how much I loved this light and shade, and the sense of bright humanity which pervades the book. It was a way, he says, of trying to capture a true sense of the Hehirs and their groundedness. “Colin and Sue are funny people. And so was Morgan. I’ve watched Morgan in their home videos, and he’s got this very distinct laugh. It’s like he’s going to keep laughing forever.” In April, when copies of About a Son reach bookshops, Morgan’s photo will grace each cover. And in telling his story so skilfully, Whitehouse brings him to life on every page too.

Extract

You’ll cross the road to where it happened. A few metres behind you is a big fence behind which the knife used to kill Morgan was found, but inexplicably, and as you’ll learn in court, not until days later. You’ll stand there so calmly, in a manner so measured, it’ll be beyond the comprehension of those who watch this clip when you upload it to Vimeo that you’re standing in the spot where your son was fatally stabbed by men whose steps you’ve just retraced. And those who do watch will look at your face and see the desire to find out exactly what happened to Morgan that night burning so fiercely it’s hard to look at for long.

The hardest part of writing the book, Whitehouse tells me, was giving the finished draft to Colin. “Before anyone else had read it, including my editor Francesca, I had the book printed out and bound with a mock-up of the cover. I went to Colin’s house and sat with him there for several hours, unable to take it out of my bag. I was terrified because I could have been delivering a grenade. I’d written so intimately, not only about his son’s murder but also about his relationship with his wife, and with his sons. I remember my hand shaking as I finally summoned the courage to take it out of my bag. That was on a Friday, and I didn’t sleep the whole weekend. On the Monday, Colin called me and said: ‘It’s good’. And that was enough.”