You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Debuts of 2025, Volume 1: Danielle Giles

Katie Fraser is the chair of the YA Book Prize and staff writer at The Bookseller. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International ...more

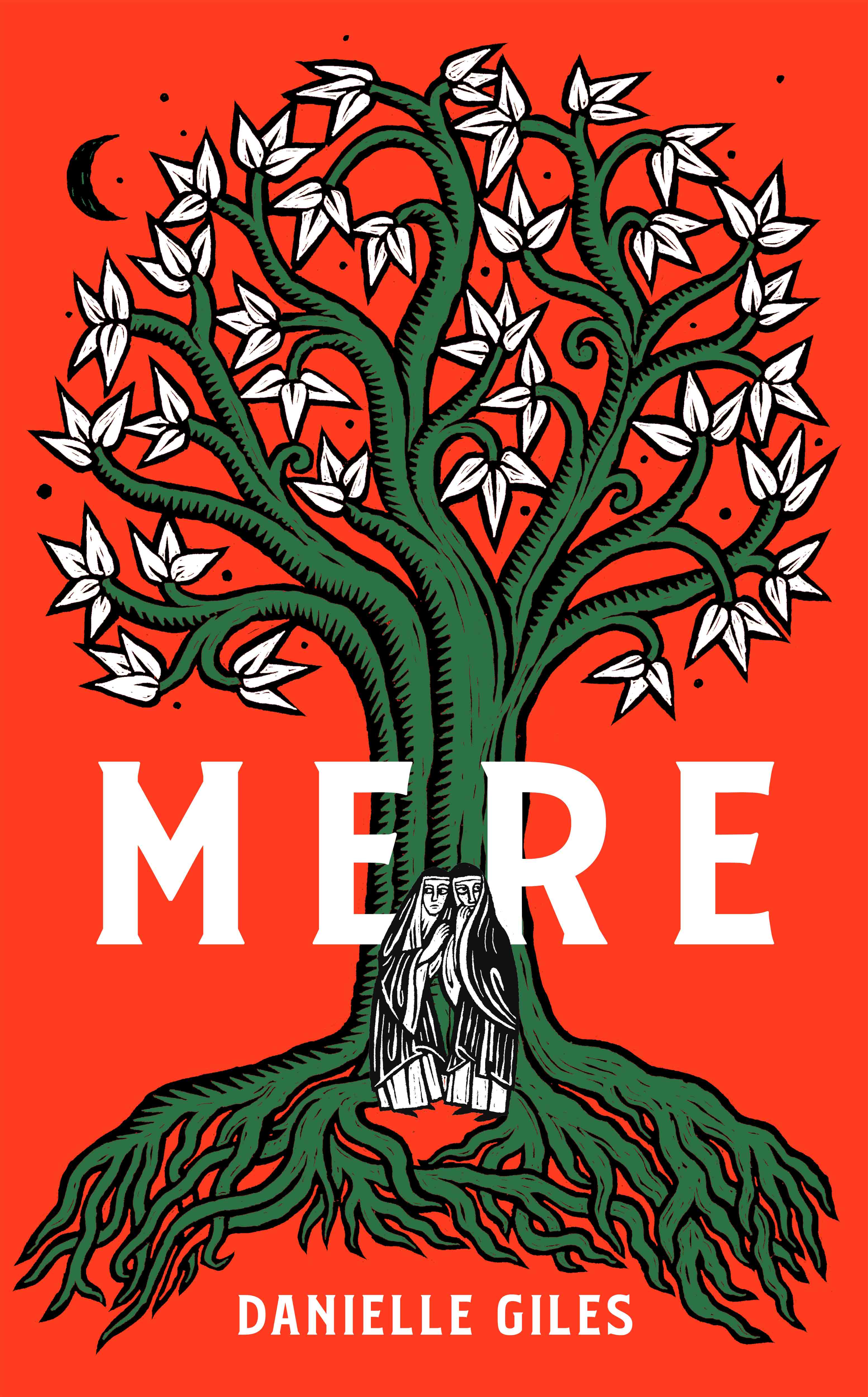

Set in 990AD Norfolk, Mere by debut novelist Danielle Giles charts the fate of a convent surrounded by marshland called the mere, an Old English term for a "sheet of standing water"

Katie Fraser is the chair of the YA Book Prize and staff writer at The Bookseller. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International ...more

“We do not know how eels procreate,” Danielle Giles tells me over video call from her home in Bristol. Although eels are not the subject of Giles’ exquisite debut Mere, the limit of human knowledge is central to the novel. “There is something kind of wonderful about the unknowability of some of these things.”

Set in 990AD Norfolk, Mere charts the fate of a convent surrounded by marshland called the mere, an Old English term for a “sheet of standing water” or “a road or strip of uncultivated land”, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. Sister Hilda is accustomed to the strange and dangerous ways of the mere—how one must approach it with care lest they become lost. Such is the fate of young Eadwig, a boy travelling with a host of others, led by Sister Wulfrun and Father Botwine, from the town of Gipeswic. After wandering into the bog, Eadwig returns changed—“devil sick”—and catalyses a series of disastrous events which threaten the reign of Abbess Sigeburg and the sanity of the convent’s inhabitants.

The skill of Giles’ writing lies in her ability to masterfully control narrative tension. The encroaching mere threatens the nuns’ ordered life, which is predicated upon certainty, worship and servitude. Rather than reinforcing the beliefs of Catholicism, the mere represents something ancient and powerful, a force deeply in tune with the natural world. “I have always been massively drawn to marshes and marshlands,” says Giles. “I think they are powerful spaces,” “liminal” environments where humans feel “a lot more exposed and closer to the natural world.” Part of the mere’s sinister quality comes from its stillness, and the idea of the marsh “looking back at you” is key. The water watches carefully as things turn to ruin in the mortal world. “Let the mere be and it will devour all of Christendom,” the novel reads.

Mere has a sinister speculative edge. The marsh transforms life at the convent and the surrounding farmland, claiming fields, livestock and human lives when the waters rise overnight. This “element of transformation and uncertainty” “really appealed” to Giles, whose childhood was spent living in an area prone to flooding in the South West. “I grew up seeing a landscape being transformed by water quite a lot.” This, combined with the tales spun by her Irish Catholic grandmother of “banshees and things like that”, created Mere’s Gothic foundation.

Exactly how those who wander into the mere become “devil sick” is left open for interpretation. It is for the reader to judge the nature of this power. Although the nuns believe the affliction is caused by the devil, for Giles it is not as clear cut: “I think it’s probably beyond that level of morality.” Instead, she refers to those affected as “infected”, but uses the term without the weight of association of a post-pandemic landscape. “It feels like a more natural process... I think it is quite interesting because obviously ‘infected’ has connotations, but actually it is describing a natural process... In the context of the novel, it’s kind of a morally neutral thing that happens. It’s more about how [the characters] react to it.”

Giles was raised Catholic and jokes that nuns loom “large” in her “cultural imagination”, but Catholicism also provoked in the author “a certain fascination with bodies”. Mere includes visceral descriptions of illness, savage injuries—caused by whippings and one gutting by an ox—and the effect of acute hunger. It is a small community, made smaller by the marsh, and Giles wanted to use this, and the characters’ response to threat, as a “microcosm” to explore “broader things that are going on both then and now”. As the convent’s population dwindles, tension mounts between the survivors while the mere sits and waits.

Against the backdrop of pain, Hilda and Wulfrun’s love shines through the suffering they both endure. Their relationship reveals a romance “that is up against the challenges that exist for a lot of people, which is how you build something when it feels like everything is falling apart and crumbling around you”.

The queer love story is part of Giles’ mission to reinvigorate the medieval period, which appears in discourse as “quite masculine”. Spurred on by the research of Dr Erik Wade and Dr Mary Rambaran-Olm, Giles “wanted to talk about the sort of things that were happening with women at the time and women in communities”. The community in the convent, and the companionship between the women, is paramount as the story unwinds. For, unlike those texts telling of a heroic chivalrous knight, Giles’ aim was “to move away from ideas of individual heroism” and toward “mutual support”. The idea of martyrdom is transposed from the individual to the collective. For it will take more than one woman to satiate the mere.