You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Debuts of 2025, Volume 1: Lucy Steeds

Madeleine Feeny is a book critic published in the New York Times, Guardian, Financial Times and Telegraph, among others, and the fiction ...more

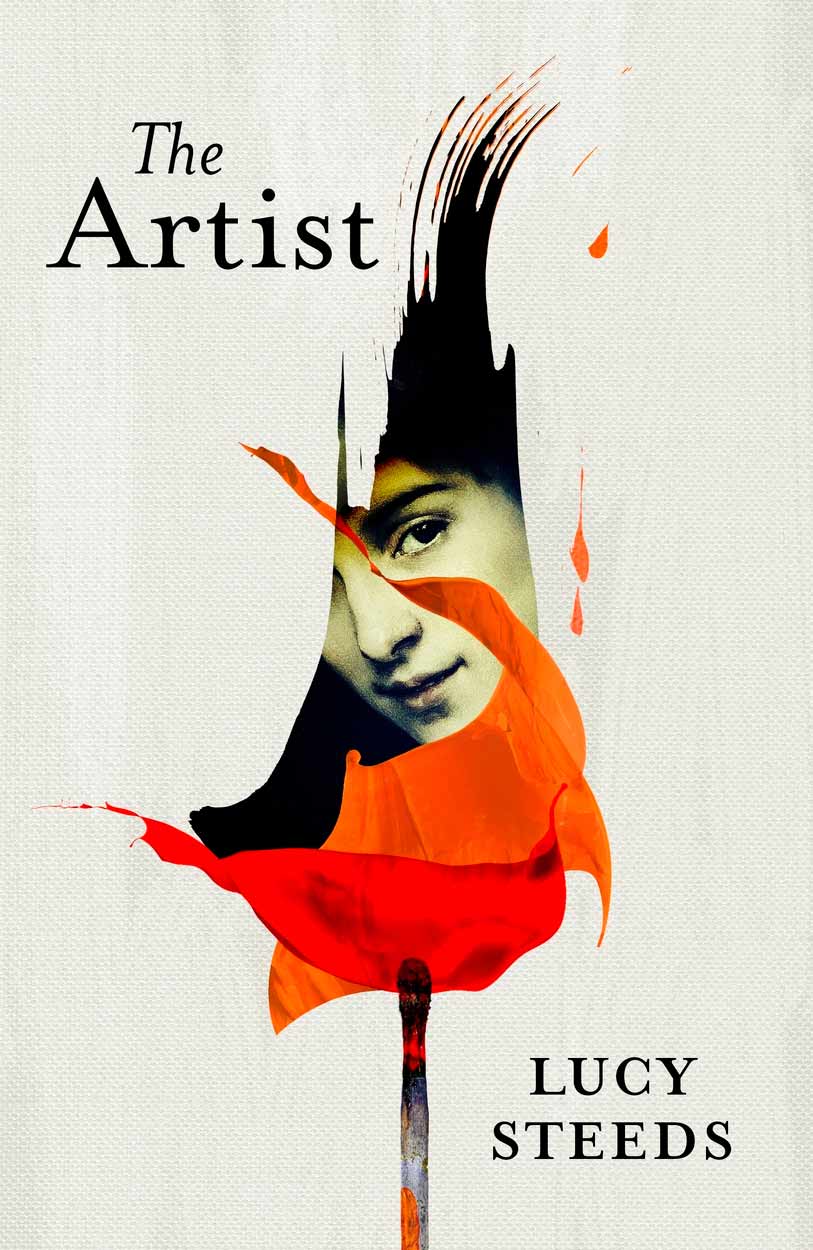

Lucy Steeds’ debut novel The Artist is a tense psychodrama of female subversion and liberation exploring the legacy of war

Madeleine Feeny is a book critic published in the New York Times, Guardian, Financial Times and Telegraph, among others, and the fiction ...more

What of the women behind the art monsters, those geniuses whose cruelty we forgive because of the masterpieces they create? “It’s not just about the art we gain from these tyrants,” says London-bred author Lucy Steeds over video call from her Amsterdam home, “but what we miss out on. What could Véra Nabokov have written if Vladimir had been running around picking up after her?” Praised by Sarah Perry, the 30-year-old’s debut novel The Artist is a tense psychodrama of female subversion and liberation exploring the legacy of war, the unreliability of perception and the hidden corners of art history. It follows a young English journalist, Joseph Adelaide, to a remote Provençal farmhouse in the summer of 1920. He has been enigmatically summoned by the reclusive (fictional) painter Edouard Tartuffe, but “Tata” will give no interview; to remain, Joseph must earn his place as a model.

So begins an uneasy dance: between Tata, painting Joseph in oils; Joseph, trying to capture the uncooperative maestro in words; and Tata’s niece Ettie, observing from the shadows—the unseen hand which primes her uncle’s canvases, composes his still lifes and organises his sales. The novel acts like a three-way mirror, each character the eponymous artist in their own way. As tensions rise with the heat and the narrative shifts between perspectives, the picture flickers beneath the reader’s gaze, reframing what they think they have seen.

While Tata’s personality dominates, Steeds was careful not to depict a straightforward villain. “He has glimmers of tenderness and vulnerability. He is trapped in a prison of his own making.” Meanwhile, Ettie’s composed exterior masks her fury, and she claims power in secrecy—like the painter Celia Paul, who found freedom in deceiving her controlling lover, Lucian Freud, and from whose memoir, Self-Portrait, Steeds takes her second epigraph.

In 2023 Steeds gave herself a year off working in academia to write a novel. Sharing her manuscript after completing a Faber Academy course, she received nine offers of representation. John Murray then pre-empted The Artist in a six-figure, two-book deal.

Steeds was living in France when she began writing, and the setting allowed her to probe the contrasts of “having a horrible time in a beautiful place”. The sensuousness of her prose is perhaps partly explained by her synaesthesia—in her case, the pairing of colours with letters, numbers and words—which helps her picture scenes vividly, but “could make you very lazy, so you need to work harder”.

She loves the art of the 1920s, particularly post-impressionists Cézanne and Van Gogh. The era was itself a time of contrasts: “Just because you were drinking champagne with Jay Gatsby, it didn’t mean you weren’t also having nightmares.” Steeds considers the scars the First World War left on minds and bodies. Avoiding the trenches, she focused on invisible histories: a conscientious objector, an Algerian conscript into the French army, a nurse and a soldier with post-traumatic stress disorder. Reading nurses’ diaries showed her how the war allowed women to grab some power and freedom.

The novel offers a fictional response to Katy Hessel’s bestseller, The Story of Art Without Men, and Linda Nochlin’s 1971 feminist essay, titled “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, which unpicks the structural barriers in their way. When Steeds read Noah Charney’s The Art of Forgery, which suggested that there had been no women art forgers, “a door opened, because the whole paradox of art forgery is that we only know about those who have been caught so, by definition, we don’t know about the best.” Steeds wrote into that gap, filling it with her imagination.

In its set-up and brooding atmosphere, The Artist recalls Yael van der Wouden’s Booker-shortlisted The Safekeep. Structuring a tale of trickery was “a headache”. “When you lay clues like breadcrumbs, you don’t know how obvious they are to the reader.” Her decision to narrate from two perspectives, Joseph’s and Ettie’s, was a breakthrough, because Steeds is interested in the gulf between what different people think they are seeing.

Steeds admires historical fiction authors who make the past feel like the present— Imogen Hermes Gowar, Katherine Rundell, Ferdia Lennon—and wants her characters to feel as vital we are today. Inspired by a summer job at the Natural History Museum, her second novel, currently in progress, is about the Second World War evacuation of the nation’s treasures to country houses.

Writing The Artist opened her eyes to the invisible labour behind a painting. She avoids specialist language and is emphatic that her book is for everyone, not just art lovers. “Many people feel excluded by the art world, and I want to say: ‘If you look at a painting and like it, that’s the most important relationship you can have to art. That’s all that matters.’”