You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Édouard Louis discusses his most autobiographical work to date

French literary sensation Édouard Louis has once again mined his personal life in a captivating new book, translated by fellow acclaimed author Tash Aw.

For the past seven years Édouard Louis has been the biggest thing in French literature, after bursting on the scene aged just 22. His autobiographical début novel, The End of Eddy, charted his struggles growing up gay in a family living below the poverty line in working-class northern France. The book was a sensation on publication: critically fêted, a monster hit at la caisse that became a culture-war touchpaper, sparking debates around social inequality, sexuality and toxic masculinity.

Louis’ follow-ups had a similar impact, also skirting the line between memoir and fiction. History of Violence saw Louis dealing with the trauma of being raped, his subsequent PTSD and the difficulty of being caught in the so-called justice system after he reported the assault to the police. Who Killed My Father, written as a long letter to his father, touches on his parent’s violent tendencies, their heartbreakingly difficult relationship and the economic conditions that left his father a physical and emotional wreck. That last part is an important component of Louis’ work—he mines his life for his art, but that personal is very political and his and his family’s lives are inextricably entwined with the structural forces of capitalism which work to keep the poor poorer.

I kind of started to dig in and try to understand how much masculine violence, poverty, parenthood and motherhood contributed to undoing this happiness

Now comes something of a coda to the first three books, A Woman’s Battles and Transformations, which looks at his mother’s experiences. She is something of an oppressive, angry figure in his previous work and here, as in Who Killed My Father, Louis attempts, if not a complete rapprochement, to somehow have a greater understanding of his mother’s motives.

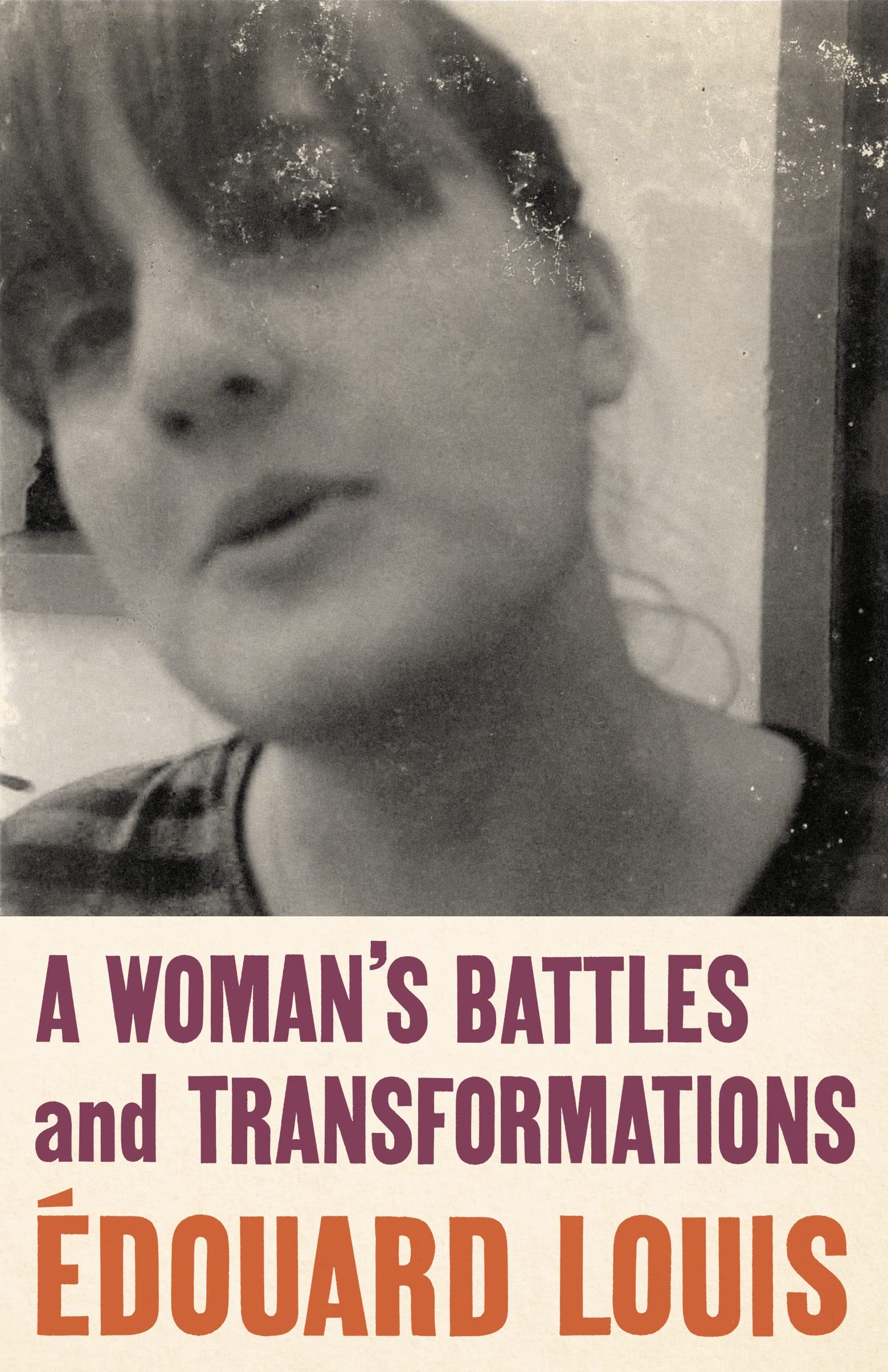

The genesis of the book was stumbling upon a photograph Louis had never seen before of his mother, in which she is young, smiling and happy. Louis says: “In my first book, and in my childhood, my mother was aggressive, violent, dark. She was always blaming me for not being masculine enough or for being too strange and I thought, ‘What happened between this mother I knew and the one in this picture? What was the starting point? How would I find the kind of archaeology of the destruction of this happiness on her face? How did she go from being such a dreamy, smiley person to being that violent?’ So I kind of started to dig in and try to understand how much masculine violence, poverty, parenthood and motherhood contributed to undoing this happiness.”

A Woman’s Battles and Transformations is a bit of a departure for Louis in that it is more obviously shaded toward pure autobiography—for example, he uses his mother’s real name, Monique Bellegueule, rather than a pseudonym as in his previous titles. Although it is hardly a straightforward memoir; it is non-linear, slipping between anecdotes, monologues, philosophical musings and family history over a brisk 120 pages. Louis says that structure was linked to translation: “I was translating into French a few of [Canadian poet and playwright] Anne Carson’s tragedies: her version of ‘Antigone’ and one of her own on Marilyn Monroe called ‘Norma Jean Baker of Troy’. I was kind of fascinated by the shape of tragedy: the shortness of it, the directness of it, the violence of it. The fact that the whole story is told in one sitting, that you close the doors in a theatre and the audience cannot really escape it.

I’ve known Édouard for many years and I never wanted to be the translator... I didn’t want that responsibility of bringing this vision of a great writer into another language

“Books can be nice and bourgeois; you are reading on the sofa with your cup of tea, you can stop, go to bed, reopen the book. I wanted this book to not be bourgeois, to be inescapable: I wanted people to see the violence that my mother went through, the violence that society was imposing on her and how much it destroyed her.”

Joie de vivre

I had a bit of trepidation interviewing Louis. Not just the usual inferiority of the monoglot English speaker when encountering a continental intellectual but, given his activist reputation, there was the tingle of dread that he might be a po-faced philosophe whanging on ad nauseum about Derrida. He was anything but. Yes, Louis does speak in wonderfully ornate paragraphs rather than sentences, but in the flesh (or, on the video screen) he is disarming, affable and funny even when talking about, say, the shackles of the patriarchy. It perhaps helps that we are joined on the Zoom by his close friend and translator of A Woman’s Battles and Transformations, the novelist Tash Aw.

Aw took some cajoling to get on board: “I’ve known Édouard for many years and I never wanted to be the translator... I didn’t want that responsibility of bringing this vision of a great writer into another language. What if I failed? And then having to face one of my best friends with that failure? So I was hesitant. But I was drawn in because I had been thinking at that time about a lot of similar things in Édouard’s book, like how my relationship with my parents, and my mother in particular, has evolved over the years. My mother had once been young, attractive and independent, but you can see how the experience and the sacrifice of marriage and motherhood can break women.”

Louis cuts in: “But I knew he would do something absolutely perfect and beautiful. And I mean, Tash is one of my closest friends. We spoke many times about my mother and my village… It was, in a way, as if we had seven years of preparation for this translation; it was the most prepared translation ever. Regarding translation in general, for me translation is a beautiful place of dispossession. I really love that and I don’t want to intervene too much—for me, the moment of translation is precisely the moment where I give up my story, my struggle, and it becomes someone else’s story. They can do with it what they wish.”

We try and pretend that literature aims to capture a universal human existence, higher cause and all the rest of that. But actually, it’s just very obsessed with the concerns of a small number of people

One of the parlour games French journalists (particularly those on the right) play is trying to fact-check and poke holes in Louis’ life story from his books, perhaps not realising that autobiographical fiction needn’t exactly follow reality. But the barest of bones biography is that he was born as Eddy Bellegueule in Hallencourt, a small, depressed, post-industrial village not far from the River Somme. His family were in precarious poverty, particularly after his father was left housebound after a horrific industrial accident. An effeminate queer kid, Louis was mercilessly bullied but he still shone at school, eventually winning a place to study sociology in Paris, where in 2013 he legally changed his name to Édouard Louis in a break with his past—the titular “end of Eddy”.

Louis’ seemingly overnight success was probably helped by France being at a point where it was debating issues of gender and class. But Aw goes further: “My not particularly clever theory is that most literature is incredibly middle-class and really the stakes are low. We try and pretend that literature aims to capture a universal human existence, higher cause and all the rest of that. But actually, it’s just very obsessed with the concerns of a small number of people. Édouard’s work just explodes that…his work actually continues a very long French tradition of the realist novelists from the 19th century and tries to drag literature into a wider domain. That’s why people recognise how real, relevant and powerful it is.”

Louis has the good grace to look abashed at Aw’s praise and before the awkward pause stretches any longer, I ask if Louis will always write about the self. Someday might he go off piste and write, say, a novel about werewolves in space? He laughs and says: “Autobiography is where I find my strength, it’s where I feel that I can kind of confront people with things that they don’t want to see. With this kind of writing, people can’t say, ‘Oh, it’s just a character, it can’t be real.’ It fits with what I want to do politically.

“We often hear people saying, ‘Oh, nowadays everybody wants to write about themselves.’ If you look at what’s published or who wins the big prizes, autobiography is a very small part of literature. So why do people have this idea it’s everywhere? It’s kind of similar to the trans panic. When transphobic people know someone is transitioning, they think everybody is becoming trans: ‘They’re invading us!’ At a completely different level, I have the impression that autobiography is creating a similar paranoia. You just need a few autobiographical works to give people the impression they are being invaded. For me, this is a good sign because it’s really challenging a certain idea of what literature is. So, I think this is just my starting point.”