You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Emer Martin’s discusses her latest novel that deals with Ireland’s past, present and future

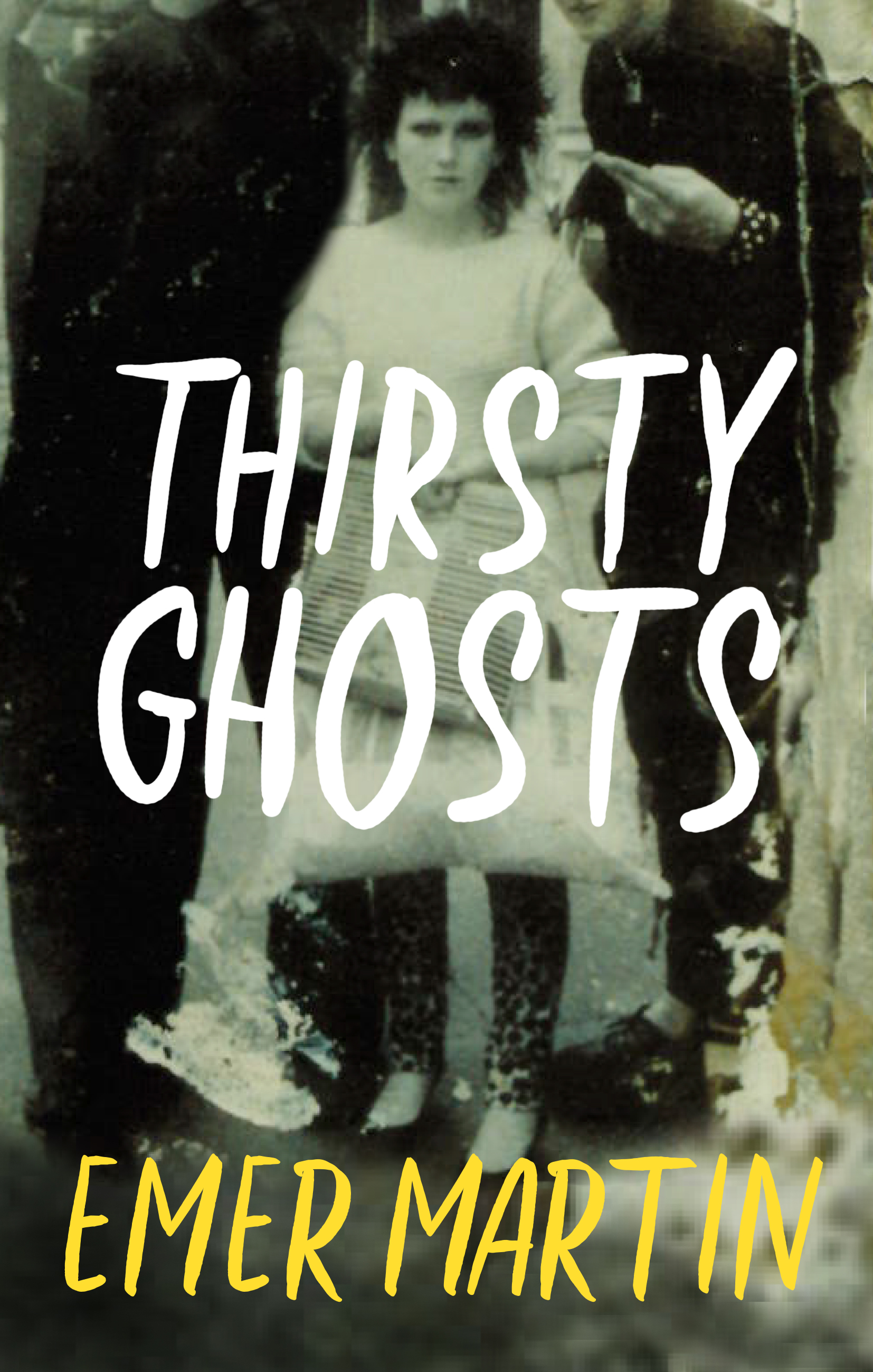

There is ambition and then there is the Great Irish Novel kind of ambition that is in Emer Martin’s Thirsty Ghosts.

In tiny bursts of chapters, the polyphonic book encompasses a host of recurring characters and timelines from Irish myth (Hag, a sort of personification of Ireland), history (ranging from 1000 BCE to the Tudor plantations of the late 15th and early 17th centuries) and to the modern day. But the bulk of the narrative concerns the Lyons and O’Conaills – families who featured in Martin’s previous, loosely related The Cruelty Men – especially in Dymphna and Deirdre, two women who in their own ways dream of escape. If that sounds daunting, it isn’t; there are pacey plotlines in each of the character arcs that keep the pages turning. It is a fine balance of the savagely funny and heartbreaking; one hesitates to say there is a Joycean scope, but perhaps the modern equivalent is Max Porter’s Lanny.

Martin appears from her current adopted home of California over Zoom – in fact, not too far from Zoom’s Silicon Valley headquarters – looking sprightly despite the 7.30 a.m. start (“I teach,” she says somewhat ruefully. “I’ve been up for hours.”)

“I guess the book was an ambitious idea,” she says. “It was me trying to come to terms with Ireland and what it was. This small island off the edge of the Atlantic that when I was growing up we used to jokingly/not jokingly call the rock of doom. I’ve lived in a lot of places where [people think] they are the best country in the world: England, France, the USA – my god, the USA… But not us. The Irish have always known their limitations, but I think there is a story in that.”

I guess the book was an ambitious idea… It was me trying to come to terms with Ireland and what it was

The idea of interlacing tales from the past and mythology with the centrepiece of the modern narrative came as Martin is “intrigued by point of contact. I spend a lot of time in Mexico and I’m fascinated by that moment when Cortés met the Aztecs—and all that came after that. Ireland had that, too [with England]. That first collision of cultures begins the long story of colonialism, capitalism and the industrialisation of power”.

Historical restoration

Somewhat left field, Martin tells me that an inspiration was the American socialist historian Howard Zinn, then grabs a copy of his seminal work, A People’s History of the United States, from a nearby shelf. She says: “My brother gave me this book when I was about 19 and it changed my way of looking at things. I thought: ‘Oh, you can write about the people that were left out.’ So even in the historical bits of Thirsty Ghosts, you never get the nobles’ view, it’s the servants’. I think it is difficult to write history like that; ‘regular’ people often get scrubbed from the record. But I think the responsibility of me in fiction is putting back those voices which have been disappeared from history.”

Martin was born in Dublin in 1972 to parents who had moved from the countryside, growing up in a suburban housing estate. She chafed at the sexist strictures of Ireland at the time: “It was very patriarchal, church dominated. In school, all we read were male authors; we were literally told girls weren’t good at maths and science. I thought ‘What are women good at then?’ I guess we were supposed to be the support act.”

In school, all we read were male authors; we were literally told girls weren’t good at maths and science. I thought, What are women good at then?

At 17 she was “done with Ireland, just done with it”, and lit out for Paris and later London to live a writer’s and artist’s life. But things did not go all to plan: “I had romantic ideas of sitting in cafés with Camus and Hemingway; I ended up au pairing in Paris and stacking shelves in a London Safeway.” All the same, it was a “wild time” living in squats, hanging with punks, careening about Europe on the cheap. She moved to New York and fictionalised her Parisian adventures as Breakfast at Babylon, which was published in 1997 by Houghton Mifflin and was hailed in America as sort of an Irish female Trainspotting. At 25, with a hit book, Martin says: “I thought, ‘That’s it, I can put my feet up and become a celebrated writer’. It is a good thing that you can’t see your future. I don’t think I would have realised how hard it is to write, stay published and keep being published. I mean, it is really fucking hard.”

Arriving at a crossroads

That said, Martin has been busy in the intervening years, publishing eight books while delving into other arts –sell-out shows of her painting; producing and directing films, including collaborating with her longtime friend Irvine Welsh on his directorial début, “Nuts”.

She has known Welsh “since the mayhem of the ’90s” when the two were part of a panel of Scottish and Irish writers at a San Francisco book festival. “I was with Colum McCann and Colm Tóibín – all the Colms – but I thought the Irish panel was too well-behaved, so ended hanging with the Scots”.

It is a good thing that you can’t see your future. I don’t think I would have realised how hard it is to write

She also went to university, getting a BA in English at New York’s Hunter College and an MFA in cinema at San Francisco State. She remained peripatetic, moving to Silicon Valley (“my partner dragged me there because he was in tech”), back to Ireland in the mid-2000s where she taught at Trinity, then a return to the Bay Area where she has been for a decade, the duration partly because her kids are in school. “But it’s been 10 years, I’m a restless person and I’m getting really, really itchy.”

The years in which Martin moved back to Ireland in the 2000s and her subsequent returns – she often spends at least part of her summers in County Meath – had her living in a nation that is, of course, far removed from the one of her early life. She says: “Ireland now is unrecognisable from the one I grew up in. And it is not just the money and economy. It is a confidence, and that we are far less parochial. And we have immigrants –people are coming to us. Ireland is multicultural and much more sophisticated.

Extract

I was born in Gestapo Ireland in the 1950s – where men weren’t allowed to think and women didn’t even exist. My name is Dympha. Patron Saint of the Mad. Yeah. I’ve heard all the jokes. I came to the Laundry at fourteen years old. The others all called me Little Poet on account of me writing me own poetry when I was little and walking barefoot by the River Dodder.

I used to put me feet in and let the river soak me and I’d suck the spirit of the water to give me strength.

Ma was told I was always sitting by the River Dodder with me eyes closed. And she found all me poems, scribbled on the backs of bits of paper. Sure, I can’t remember even one of them now. They had always been telling me than if I didn’t behave, I’d go to the Magdalenes and that’s what they done – and they never came looking for me after. All the blame went on them nuns but they didn’t have to come looking for us, it was our own famblies who shoved us in for the most part. Of course, the nuns were there to suit them, and the Guards to send us back if we ran. What a racket.

“But this creates tension about who we are. Are we just a country of data centres which gives tax breaks to Google and Amazon because that drives the economy? How does that square with old traditional Ireland, the thing that makes us unique? Are we going to embrace multiculturalism and expand our view of what Irishness is, or will there be the pitfalls of other European countries of racism and moving to the far right? We are at a crossroads. But I tell you, it is fertile ground to write about.”