You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

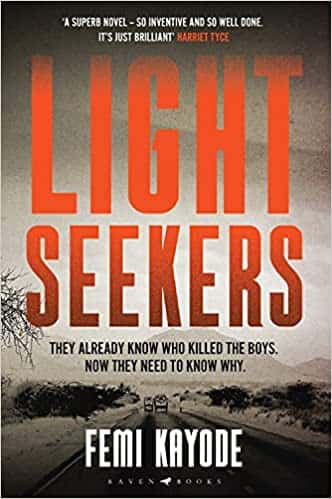

Femi Kayode on his début novel Lightseekers

Femi Kayode’s début novel, which is based on the real-life lynching of four undergraduates in Nigeria, is the first title in a forthcoming series from Raven Books.

Femi Kayode’s début, Lightseekers (Raven Books), opens as an angry mob murders three students in a Nigerian university town. Based on the real-life lynching of four undergraduates at the University of Port Harcourt in 2012, it is not for the fainthearted: “When the young men fall here, they’re kicked further into the ground; their blood mixing with sludge. By the time tyres are thrown over their heads like oversized necklaces, and the smell of petrol wafts so strong that some in the crowd cover their noses, madness has staked its claim on what is left of the day.”

The first in a series, Lightseekers is not your usual whodunit: we know from the start who killed the boys. Instead, Kayode continues his story a year later, after the father of one of the victims hires investigative psychologist Dr Philip Taiwo to go to the town of Okriki, where the killings happened, and find out why. As Taiwo investigates, he discovers dangerous secrets held by inhabitants who are desperate to get rid of him.

If we don’t really understand why people do the things they do, especially as a collective, we cannot change society

“We know the crime, we know who did it, it’s on camera,” says Kayode, who is Nigerian. “But do you know why it was done, do you know the constellation of events and history and culture that come together to make this possible? I come from a school of thought that believes crimes don’t exist in isolation. And I’ve gotten a bit frustrated by the Western-model of crime fiction, where it’s so focused on the serial killer and doesn’t address the society that gave rise to the serial killer. We’re so focused on finding the killer that we don’t wonder why it’s not safe for a single woman to walk in the dark. What is the society that is not allowing young women to walk on the streets on their own? We’re not investigating that, because we’re so focused on finding the killer, and when we do, we move onto the next ‘Who did it?’ But I think when we start finding out ‘Why did it?’, we start to look at certain sociological, systemic issues around our community, and what we can do to make a change.”

Wide-ranging interests

Kayode’s interests, and accomplishments, are wide-ranging. He took a masters in clinical psychology after completing his first degree in animal science in Nigeria, but decided that he was “not a therapist, that I was not interested in listening to other people’s stories”. He went into advertising, where he has worked in fits and starts for the past two decades.

“Everybody that works in advertising is a closet painter, filmmaker or author; we all dream of doing something grander and more super-creative than what we consider advertising to be, which is pop culture,” he says. “I think maybe one of the things that advertising really gave to me was a sense of simplicity, having a big idea that you can break into little chunks of explanation. But I’ve always wanted to write a novel. I’ve worked in film, I’ve worked in radio—for me, the genre was the last frontier.”

Kayode is currently a partner in a firm in Namibia—he’s speaking on Zoom from his office—but has also been a Packard Gates Fellow in Film at the University of Southern California and a Gates Fellow in International Health at the University of Washington, with a sideline in writing films and soap operas in Nigeria. While he very much recommends the latter—“it’s such a disciplined culture, it’s literally being a factory, immediate creativity on demand”—he wanted more control of the creative process, and felt the only way he could get that was through writing a novel. A glutton for education, he decided the way to do this was to go back to university. “I like school, and I didn’t think that I was the type of person that could just start writing a novel. I thought I had to go to school to do it.”

He applied to the University of East Anglia’s MA in crime fiction, because “any story has some kind of crime in it—any conflict has some kind of crime. Drama is about crime, there are crimes of the heart, there are crimes of betrayal.” But the letter inviting him for interview went into his spam. Undaunted, he took a postgraduate degree in futures studies instead, but UEA contacted him in the middle of it to ask why he had not got back to them. Once he finished his postgrad, Kayode took the MA at UEA, with Lightseekers written as his thesis while he was there.

Kayode had initially considered writing about the Port Harcourt killings as a “non-fiction novel”, inspired by Truman Capote, but found the ethics around doing so to be too complex. “You’re talking about victims, you’re talking about families of victims, I knew that I was going to be walking on eggshells, and it might actually limit my creativity, so that’s when I decided to embrace fiction,” he says.

In his acknowledgements for Lightseekers, however, he writes of how the novel was written to “honour them and the victims of vigilantes across the world”.

“This was real—it was four boys, four undergraduates who were accused of theft by the community, and they were mobbed, and they were lynched, and they were killed. What really always fascinated me about it was the fact that everybody just sort of accepted it as a crime. You know, this terrible thing happened in this village, and we just go on. And I felt that the explanations and the reasons that were being given were very lacklustre and very superficial. They didn’t actually unpeel the layers of how we got here. And we can’t do something if we don’t understand—we can only complain and whine. But if we don’t really understand why people do the things they do, especially as a collective, we cannot change society.”

Considered choices

Kayode’s protagonist, Dr Philip Taiwo, is Nigerian, but has spent most of his adult life in the US, so finds himself both part of and an outsider to the community he is investigating. This was a deliberate, considered choice for Kayode, who came up with the character in a classroom where the majority of his classmates were Europeans. “I sincerely wanted to show these people my world. I wanted them to go into my world with me,” he says. And having lived outside Nigeria himself for almost two decades, he could speak to Taiwo’s experiences.

His manuscript won him the Little, Brown/UEA Crime Fiction Award, which in turn landed him an agent and a two-book deal with Raven Books, after a four-publisher auction.

“Before I started school [at UEA], I just wanted to write a book. But in class, understanding the genre more, and the commercial aspects of having a series, I knew this was going to be a series,” says Kayode. Involving a murder in a church, and delving into religion in Nigeria, he finished Gaslight (Raven Books), his second novel, in September, and is in the middle of his second draft.

Taiwo is a wonderful creation, human and flawed—I particularly enjoyed how Kayode writes his relationship with his brilliant, critical wife Folake, a lawyer, who has little faith in his ability to find answers. “It would’ve been nice if my wife had said instead: ‘Go, Sweets. If anyone can find out what led to the mobbing and burning to death of three undergraduates, you’re the one. You’ve got this.’”

Kayode says: “Taiwo is a hard worker. He’s not a superhero, he’s not super-intelligent, he’s not Sherlock Holmes. He puts in the work, and that’s what makes him so special to me.”