You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Frederick Forsyth in conversation about writing, journalism and his autobiography

Philip Jones

Philip JonesPhilip is editor of The Bookseller, a position he took up in August 2012. Before that he was deputy editor, having first joined the ...more

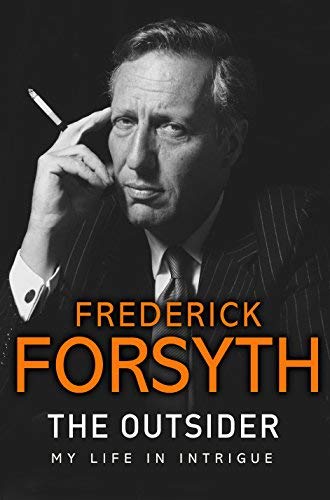

The man behind a string of bestselling thrillers has opted to write about his own life—although it’s far from a conventional memoir, he tells Philip Jones

Philip is editor of The Bookseller, a position he took up in August 2012. Before that he was deputy editor, having first joined the ...more

In Frederick Forsyth’s eventful retelling of his life story, the thriller writer—famous for bestsellers such as The Day of the Jackal, The Dogs of War, The Fourth Protocol and most recently The Kill List—reveals how penury first prompted his move into fiction writing, how he almost started the Third World War and what he really thinks of the BBC, for which he briefly worked as a reporter.

Forsyth is a private man and his memoir is indicatively titled The Outsider. He dislikes publicity—even when his books are published—and says he had long resisted the offer of writing his life story. Ever the free spirit, he came up with another approach. “I’d fended off various suggestions for 10 years and I finally decided I didn’t want to do an autobiography because that would involve scholarship and research. So my wife suggested I make it a series of anecdotes—60 of them.”

There were periods when nothing much happened, and I didn’t even mention them

Forsyth admits that he never made notes, kept a diary or took photos of himself. His journalism was entirely focused on others. ”So I just went back into my memory and started at the beginning—’what was it like in Kent in 1940?’—and moved on from there. Fortunately, old men remember the distant past better than what happened yesterday.”

The vignettes are chosen for their plots, as one would expect for an expert in storytelling: “There were periods when nothing much happened, and I didn’t even mention them.” Fortunately, his life has been eventful. The young Forsyth is rarely out of trouble and headstrong. In his early days he survived a horrendous car crash—he narrowly avoided having his hand amputated, thanks to the attentions of a retired surgeon—and a knife-fight with an Algerian in a flat in Paris (Forsyth carried the bigger knife).

As a young man he travelled relentlessly, learning to speak French, German and Spanish. He could pass as a native when he wanted to, but one of his tricks as a foreign correspondent was to mask his fluency so that others would speak freely around him. National Service allowed him to pursue his ambition to learn to fly, but ultimately his desire for travel led him to journalism.

Forsyth began, as many journalists do, at a local newspaper—in King’s Lynn—and found his way to Reuters, where his ambition to travel overseas was realised with postings to Paris and East Berlin (where his reporting of a military rehearsal almost sparked the Third World War).

Eventually he landed at the BBC, quickly discovering that its “vast bureaucracy” and obedient attitude to the government didn’t suit his temperament. In the late 1960s his coverage of the Nigerian Civil War—he countered the BBC/establishment line that the dispute was only a minor one—led to his departure from the organisation and the smearing of his reputation as a journalist. It still riles him to this day; he writes of how “this coterie of vain mandarins and cowardly politicians stained the honour of my country forever”.

The Researcher

Authoring a novel was his way to get himself out of the “mess”. He penned The Day of the Jackal over 35 days while staying on a friend’s sofa. “I just wanted to make a living. But actually [writing] was a bad way of making any money: if it works at all it is the slowest way of making any money, because it doesn’t come through until year three—if it comes through at all.”

The research was the big parallel: as a foreign correspondent you are probing, asking questions, trying to find out what’s going on, and probably being lied to

Fortunately, Forsyth struck gold. Even if no one at the time predicted its success, his timing was immaculate, beginning in the early ‘70s just as mass-market paperback publishing was establishing itself. “No one knew The Day of the Jackal would do what it did. It was launched with no pizzazz, perhaps a cocktail or two. But by book three, The Dogs of War, I realised I wouldn’t have to go back to the ranges of Africa or the jungles of Vietnam. I could sit at home and write novels.”

There are similarities between the two careers. “The research was the big parallel: as a foreign correspondent you are probing, asking questions, trying to find out what’s going on, and probably being lied to. Working on a novel is much the same, except you probably have longer to write it. I give myself six months, but in journalism it would be much shorter. But essentially it’s a very extended report about something that never happened—but might have.” Forsyth was able to draw on his reporting experiences: there were repeated attempts to assassinate French president Charles de Gaulle when he was stationed in Paris, and he mixed with mercenaries during the Nigerian conflict.

Forsyth says that all authors are only ever half in the room—”the other half is detached, watching, taking notes”—and that the solitude provided to him by being a writer suited him. “I’ve always preferred not to join, so I joined nothing,” he says. “I used my separateness.”

Writing is one of the gentlest jobs because you don’t have to crush anybody

He still maintains this detachment, regularly declining invitations to attend literary occasions, such as festivals. “It’s all about me, me, me. From what I read about them, they are exercises in self-promotion and self-worship.” He may relax the stance a little when this book comes out. “I’ve long taken the view that I owe the publishers not to be churlish about promotion, so we’ve cut a deal about a certain number of days and interviews. And then I’ll go back into my shell.” Forsyth will attend the Times Cheltenham Literary Festival and the Sunday Times will run extracts from the book. He will also travel to New York to publicise the book in the US.

The crusher

Forsyth currently writes a weekly column for the Daily Express—“a pulpit for an old man to rant”—but the book is somewhat softer in tone than those more trenchant polemics. The Outsider is dedicated to his two sons (”in the hope that I was an OK dad”) and the final chapter features a 70-year dream being fulfilled.

One senses that the longer form rather suits Forsyth, allowing him to channel his zest for experiences into his writing. “Writing is one of the gentlest jobs because you don’t have to crush anybody,” he says. “When I was a teenager, I had a raging hunger to see everything and go everywhere and do everything. I was a young man in a considerable hurry. But that abated, thank God.”

Is Forsyth really done with writing? He has published 17 novels in a 45-year career, the last being The Kill List, published in 2013. “I was never a compulsive. I never had a message for the human race. I called myself a mercenary because I did it for the money, not the fame or the glory. I’ve done most of the subjects—is there anything left? Besides, at 77 it is time to think about the other things I want to do before I pop. There are a couple.”

One last adventure for the outsider? Undoubtedly.