You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

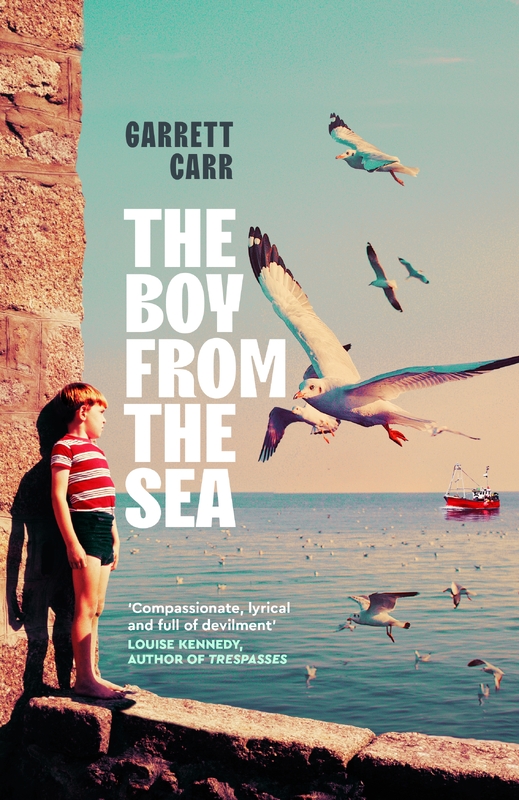

Garrett Carr's adult debut explores emotion, and the challenges we face when articulating it

"How do we talk about people who are cut off from their emotions?", asks Carr’s The Boy from the Sea.

Garrett Carr’s adult fiction debut, The Boy from the Sea, was born from the author’s interest in the articulation of male experience and emotion, and the “creative or technical problem of: ‘How do you talk about people’s emotional lives when they themselves don’t have the vocabulary, don’t have the interest in doing it?’”

Set in 1973 in a close-knit fishing community on Ireland’s west coast (in Donegal, where Carr hails from), The Boy from the Sea begins when a baby is found abandoned on the beach and is taken home by fisherman Ambrose Bonnar to his family—Christine, his wife, and Declan, his young son, with Christine’s father and sister living just down the road. The baby—and the boy he becomes—mystifies and confounds the town. The story follows the impact of his arrival on the family and the community as he is welcomed by some and eyed with suspicion by others, not least his brother Declan, with whom he becomes entangled in what threatens to become a catastrophic, life-long feud.

When we meet in Pan Macmillan’s central London office ahead of the annual Picador New Voices event (6th November 2024), Carr tells me: “Reading lots of contemporary fiction about women, by women, they would feature these emotionally articulate people—women, mostly. Take Sally Rooney, for example. Emotional self-analysis is kind of a theme and an engine for these stories. The characters have this great understanding of themselves, and they’re very well read, so they’re able to articulate themselves in all sorts of subtle ways. And I was like: ‘What about the men who can’t do that, you know?’ So, in some ways that’s where it began.”

He saw it as “a challenge”, but “something worth doing”. “A lot of people who are carrying emotional weight, maybe they’d be much happier if they could articulate and look at themselves with some perspective,” he says. Originally, Carr set about writing the novel from young Declan’s perspective (in a notebook that would be lost and, miraculously, returned five years later), but his question remained: “How do we talk about people who are cut off from their emotions? How can they narrate that themselves? I wanted it [to be] much more direct, more textured about these emotional conditions.” So, Carr began to tell the story in the communal voice of the town, which “is able to say what drives people”.

“The problem is, you [can] get into an area where these men go by sort of emotionally stunted, and like something is broken in them. That’s sort of miserable,” he explains. “But that’s not what I wanted, because these are still essentially good people who have good instincts.” Carr points to a scene in the novel in which a group of men in the local pub pool together money for the Bonnar family. “It’s this bunch of men who probably don’t have a great emotional range, but they understood that they wanted to do this thing, and they also knew how to handle it, like they knew that they should write something on [the envelope], et cetera. I write that: ‘Their senses, when it came to such things, were as fine as you get in a whole warren of rabbits’. I was trying to find that space where people—yes... they don’t have a great emotional vocabulary—but there’s still good instincts for how one should behave.”

There’s some urge for me to understand my father, and for me to leave [my sons] a kind of message... I wanted to write something that explains me

This male, communal narrative voice “does have perspective and does have a bit more emotional understanding [...], but then I think it was just good for the funniness,” Carr adds. “It can be opinionated and wrong. A bit confused and sometimes ill-informed and sort of cheeky. A bit of a character.” The author sees it, simultaneously, as one character and “seven or eight guys, probably in their 50s, in the Ship Inn”. As we talk, Carr refers to the voice in the singular male pronoun, telling me: “I do kind of think of it as one person, really, but he’s just really presumptuous. He says ‘we’, so whatever he thinks, it’s what everybody else thinks.”

This approach was also a way for Carr to capture a place and time. “I think part of a novel is about just witnessing the place,” he says. “You just think: ‘This is a special place, and somebody should record it.’ That’s part of the project of the novel, I think. Simply to record. And nobody else was doing it, you know, because fishermen, like my father, just tell people, they tell you a story at the table, they never write it down.” When I ask him why he decided to tackle his first adult novel now, after a non-fiction book (The Rule of the Land: Walking Ireland’s Border, Faber) and a number of YA books, Carr explains the role fatherhood—the connection with his own father, and his own sons—has played on him writing a novel so deeply concerned with being a father, a brother and a son.

Of the simmering feud between the two brothers in the novel, Declan and Brendan, Carr says: “A key tension in the novel is: ‘Will they grow up in a way that prepares them for life? Or will they damage themselves and each other in a way that they’ll never entirely get over, because this is such a delicate time?’ There’s a junction here. Which way are these boys going to go? The danger that Declan and Brendan are into, and the word appears towards the end, is that they’re going to grow up with a fundamental sense of shame.”

He continues: “Partly, there’s the question of: ‘When could I have done it?’ I would not have had the emotional perspective on myself, like Ambrose. [And] part of my impulse here is, I have two sons, and I’m now getting to the age my father was when he died, my son to the age I was. So there’s something going on there. There’s some urge for me to understand my father, and for me to leave them a kind of message. I wanted to write something that explains me.”