You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Georgina Lawton on exploring identity and erasure in her new memoir

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

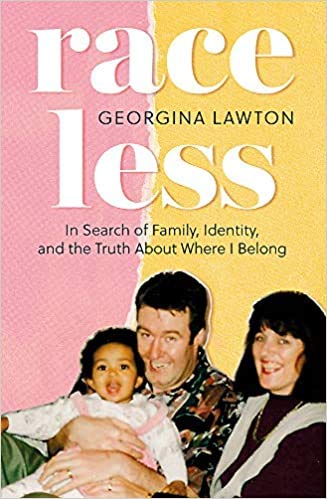

Journalist Georgina Lawton’s new memoir Raceless explores erasure and identity through the prism of her own upbringing as a mixed-race child of two white parents

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

Ideas from our parents form the backbone to our identities… they condition us in more powerful ways than lessons from any book or religion ever could. Now the tale had been destroyed. So what did that mean about who I thought I was?”

Georgina Lawton enjoyed a stable and happy childhood in Surrey, the elder child of two loving white parents. And yet the reality of her brown skin and mixed-race appearance was never acknowledged. This family colour-blindness was later revealed as a way of keeping the secret truth of her origins: that although her white Irish mother was her biological parent, her white English father was not.

Now in her late twenties, freelance journalist and writer Lawton tells the complex story of her upbringing, and her challenging journey of self-discovery as an adult, in a compelling memoir titled Raceless. Reading it as a white person made me think anew about issues of race and identity, some I had scarcely considered before. For Raceless is both the story of one—as it turns out—blended family, and also an incisive and political book about bringing to an end the “denial and erasure of minority groups”, so that we can “build a future in which a mixed family is neither taboo, nor a talking point”.

I wanted to marry the personal and the academic, and create a project that was reflective of me, but which also elevated the stories of people like me

I speak to Lawton via Skype: she is currently living in Lisbon while working on her next book. She first wrote about her search for identity three years ago in a series of columns for the Guardian, has since been interviewed on BBC Radio 4, and currently hosts an Audible podcast titled “The Secrets of Us”. So when did she start to think that her experiences might become a book?

“My Guardian columns brought me into contact with other people around the world who were sharing experiences of misattributed identity, of transracial adoption and of problems with DNA tests,” Lawton tells me. “I began to see that maybe my story wasn’t as weird as I initially thought, and that there was scope to expand it. In the book, I wanted to marry the personal and the academic, and create a project that was reflective of me, but which also elevated the stories of people like me.”

Journeys of discovery

Lawton traces the trajectory of her dawning realisation that she did not look like the rest of her family. “I became cognitive of my racial difference aged five, after another child in the playground at school told me that if I kept scratching my brown skin it would turn white. But whenever I brought the subject up at home, my parents would say: ‘We love you and we don’t need to talk about that.’ When I got older, they’d say: ‘Well maybe you’ve inherited your looks from a distant ancestor on your Mum’s side on the west coast of Ireland.’ So it was difficult to continue a conversation with my parents about what I looked like when that conversation was constantly being shut down.

I know it sounds surreal, but that was my reality.”

Once in her teens, Lawton began identifying as mixed race. “Because that’s what other people told me I looked like, even though I didn’t know what my mix was. But at that age I didn’t know where to get a DNA test, or what a DNA test even was. And I think on some level, I knew that it would cause disruption; that it would take me away from the family that loved me. Only later did I come to understand that I could be black, and still my mother’s daughter. And still my father’s daughter too.”

In her early twenties, Lawton lost her father to cancer. A year after his death, she experienced a second tidal wave of grief when a DNA test revealed that there was 0% chance that he could be her biological father. “It was horrific; like losing him all over again,” Lawton tells me. While she does not absolve him from complicity in the conspiracy of silence that surrounded her origins, she makes movingly and abundantly clear in Raceless just how close her “Daddy’s Girl” relationship was with this man, who had never once sought to distance himself from the daughter he knew was not his. “I’m really proud of the writing I’ve produced about my Dad; this man who could have rejected me but who actually went above and beyond to love me as his own.”

So often in the UK, we gloss over race because we’re scared of looking racist or of being dragged into a conversation about race

In the wake of her father’s death, Lawton embarked on a period of global travel, in a bid to forge an identity outside her family; spending time in New York, and in locations across Latin America. “Travelling has given me so much. Once I stepped outside of the loving community in Surrey in which I grew up, I could see that there were people who looked like me in all these other places around the world. And that helped me see myself as part of this diaspora community that I never been encouraged to interact with before. And through that process of moving, I started piecing together who I wanted to be.” Lawton’s global travels have inspired a second book: Black Girls Take World: The Travel Bible for Black Women with a Severe Case of Wanderlust, to be published by Hardie Grant in April 2021.

An ongoing search

It was while she was in Nicaragua that Lawton received the results of another DNA test which showed her to be 43% “Nigerian” (though this means only that she has genetic markers specific to Nigerian people, not that her biological father is definitely from Nigeria). Her subsequent attempts to find him or a close relative are ongoing: a period of therapy and counselling—some of it alongside her mother, against whom Lawton’s understandable rage was directed for a while—has helped to finally unlock some of the mystery surrounding her mixed-race identity.

Raceless is much more than one family story however, powerful though that story is. The consequences of Lawton’s race-blind upbringing are instructive for all of us. Says Lawton: “So often in the UK, we gloss over race because we’re scared of looking racist or of being dragged into a conversation about race. But the consequence is that those with black or brown identities are not able to fully realise who they are: my colour-blind upbringing left me feeling torn between two worlds. I fully understand my parents’ choices. I try to put that across in the book. And I was celebrated as their child in many ways. But why was my identity not celebrated too?”

Extract

After all the sweating and planning and pushing and crying that took place in Queen Charlotte’s Hospital in Hammersmith on the afternoon of 12th November, a baby girl was born. There were no difficult words exchanged on the day, no heated discussions, no angry tears. There was no questioning of my mother’s fidelity, no dramatic hospital walkout. There was simply a new family.

But it was not the baby they had been expecting: they both could admit that privately, although not to each other. As she gazed down at the gurgling bundle in her arms, a cocktail of emotions swirled through my Mum’s body and made her dizzy. She was floating on a cloud of euphoria, but as she came to, she could see that the actions of her past had invited themselves into her present, and now they were here to stay.

I ask Lawton what she hopes Raceless will bring to the conversation about race and identity. “I hope it will open up more dialogue about colour-blind upbringings. I get a lot of messages from parents of black and brown children asking, ‘How shall I raise my kids?’ It’s been hard to know what to tell them because I don’t have children of my own. But now I can say, ‘Read this book.’ And if white parents and families also have difficult conversations about race as a result of reading it, that would be amazing as well.”