You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Granta Young British Novelist Eliza Clark discusses her new short story collection

Madeleine Feeny

Madeleine FeenyNew Titles Fiction Previewer

I compile the monthly New Titles: Fiction. A freelance critic and editor, I previously held ...more

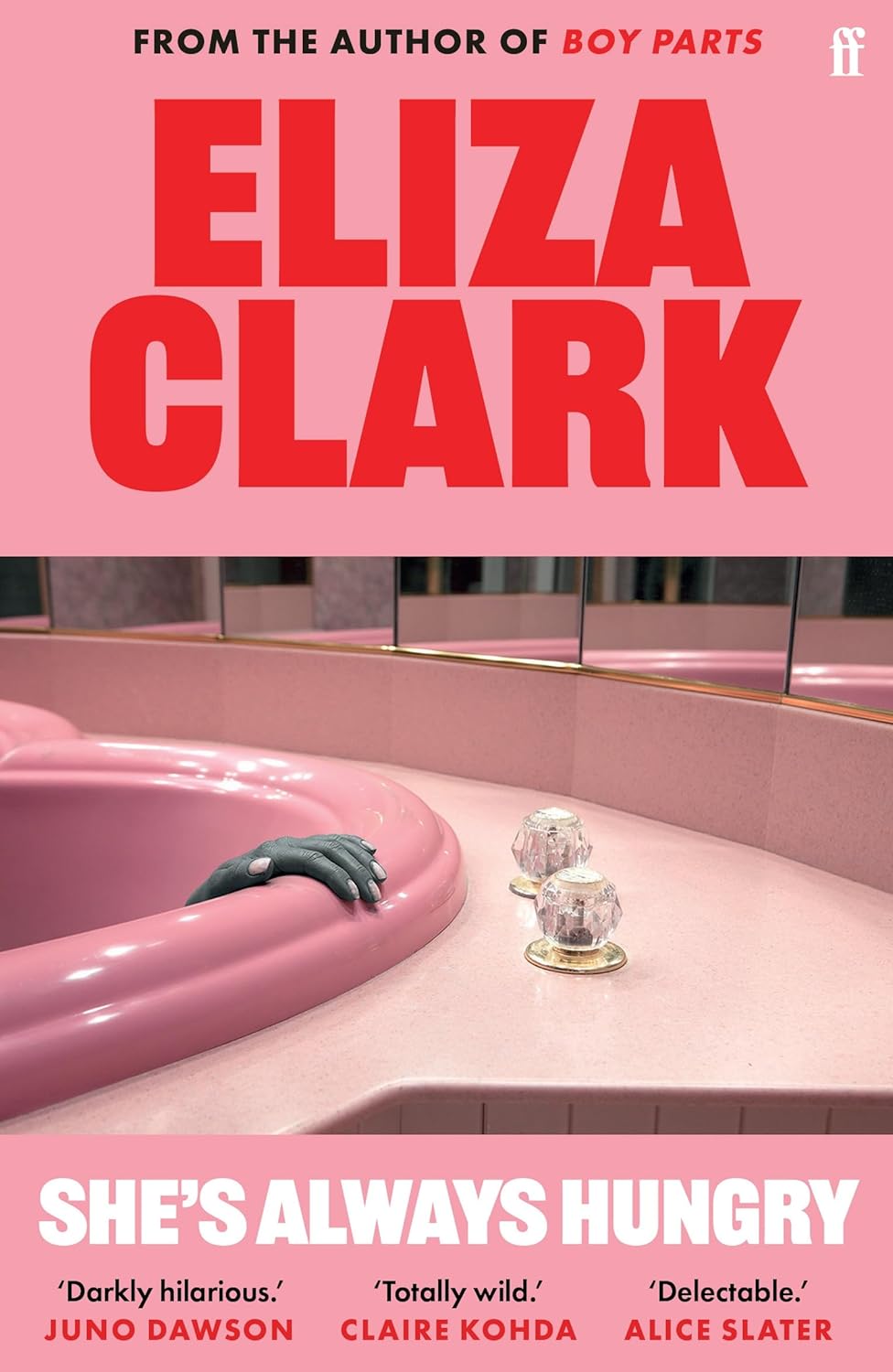

She’s Always Hungry is a riotously inventive short story collection, spanning body horror, fantasy and speculative fiction

New Titles Fiction Previewer

I compile the monthly New Titles: Fiction. A freelance critic and editor, I previously held ...more

Eliza Clark is not one to stay in her lane. The Newcastle-born art-school graduate cut her teeth writing teenage fanfiction, wrote her first novel aged 24, pitched it anonymously at a Mslexia event she had organised and signed a book deal with indie press Influx six weeks later. Boy Parts, a subversive thriller about a female photographer in a destructive spiral, was published in July 2020 and did “well for what it was”, but when she opened her royalty statement the next winter, she got a shock: it had gone viral on TikTok.

In April 2023, Granta unveiled its once-in-a-decade list of the 20 best fiction writers under 40 and Clark’s inclusion, three months before the publication of her second novel—a chilling portrait of a decaying seaside town where teenage girls have committed a horrific murder, framed as a true-crime investigation—primed the literary world to take Penance “more seriously”. Now, at the grand old age of 30, just when we had her pegged as a thriller writer, she is publishing a riotously inventive short-story collection, She’s Always Hungry, that spans body horror, fantasy and speculative fiction, all laced with her salty, pitch-black humour.

Fiction reveals its author’s subconscious preoccupations and, for Clark, these are food, parasites and lack of control over the human body, “a terrible cage that you’re trapped in for your entire life”.

“It gets worse, the older you get, and it breaks in really weird ways,” she says, sitting in her local south London café. “I’m a bit of a hypochondriac. I hate bugs, and I’ve always found infestation really disgusting.” Channel 4’s “Bodyshock” documentaries, a childhood ant invasion, a disease that makes starfish pull their own limbs off: such seeds have been germinating in Clark’s imagination and take root in these 11 stories.

It feels like the entire industry is designed to make people insane. It creates this crabs-in-a-bucket mentality between authors

In “Hollow Bones”, a parasite embeds itself in the body of a girl on an alien spaceship. In “Extinction Event”, scientists tasked with reversing climate change discover extraterrestrial lifeforms that can clean air—but at what cost? Clark, who has always struggled with existential dread, finds climate anxiety so upsetting that it is hard to write about. “Shake Well”, about a black-market skin treatment, is a response to her own “distressing” experiences with acne, while the Swiftian satire “Build a Body Like Mine” advocates an unorthodox weight-loss solution. The customer-reviews spoof “The Shadow Over Little Chitaly” was written during the lockdown takeaway boom, when Clark was hooked on the Instagram account @takeawaytrauma.

She attributes the stories’ diversity to their six-year writing period, between 2016 and 2022, when she refreshed the collection for Faber, who became her publisher with Penance. Some evolved during her mentorship with author Matt Wesolowski, funded by New Writing North—a formative experience that motivated her to complete stories and start submitting them for publication.

There is something of a self-fulfilling prophecy around short story collections, she says. “It’s probably going to be a bit easier for me because I already have an established audience, but I do wish there were more of them. It can feel like George Saunders or bust, and I really like George Saunders, but there should be more than one person who’s allowed to write literary short stories.”

Clark mainly reads backlist genre-crossover fiction—Stephen King, Terry Pratchett—and thinks much that was written 20 or 30 years ago would win a Booker Prize if it was published now. She’s been reading “horny vampire books” by Poppy Z Brite (now William Joseph Martin) and Kushiel’s Dart by Jacqueline Carey, “the grande dame of the romantasy genre. The world-building is so dense and impressive, and the line-level writing so good that anybody being sniffy about that stuff should just read more books.”

Her collection’s title story is set in a matriarchal community where a boy secretly keeps a mermaid, while the very funny “The King” is narrated by a cannibal goddess bossing it in marketing until the apocalypse allows her to assert her full supremacy.

Gender and power are enduring themes, and Clark is starting to write more male perspectives, as female narrator is her “default setting”. Her third novel, currently in progress, is in the “speculative, psychic fantasy space” and marks her first foray into third-person narration. Since starting work on the TV adaptation of Boy Parts (which has also been adapted for stage), screenwriting has become her “day job”, and she

has other original projects in development. The regular pay structure makes it much more sustainable than publishing.

“It’s such a shame that many very normal people are being strangled out of the industry, and it’s really difficult to sustain a writing practice.” Clark took a 50% pay cut for a job at Mslexia, a magazine for women writers, and later worked for Arvon Foundation, but she was able to take that risk because she was young and without dependents. She adds: “I come from a very regular background, and it was so difficult for me to break in.” She wishes there was more Arts Council funding and more support for writers outside the 18-25 bracket, and that advances were spread more fairly across established and newer voices. “It feels like the entire industry is designed to make people insane. It creates this crabs-in-a-bucket mentality between authors.”

Accordingly, she handed the keys to Twitter over to her “unpaid social media intern slash fiancé” before the Granta announcement. She banned friends from sending her TikToks about Boy Parts and remains shocked that she didn’t get “eaten alive” by the BookTok community. Perhaps its flagrant transgressiveness felt refreshing to readers weary of a “reflexive kind of puritanism”.

Unusually, She’s Always Hungry comes with a content warning. Some readers have found the opening of Penance disturbing and Clark was particularly concerned about the first story because she knows how easily eating disorders can be triggered: “I write very horrible books, but I am actually really nice, and I don’t want to upset anybody.” Could the dark side be losing its allure for Clark? Right now, every substantial idea feels “really bleak” but who knows, “maybe I’ll become less morbid with age and do a romcom”.