You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Hana Tooke talks about her debut, careful plotting and celebrating difference

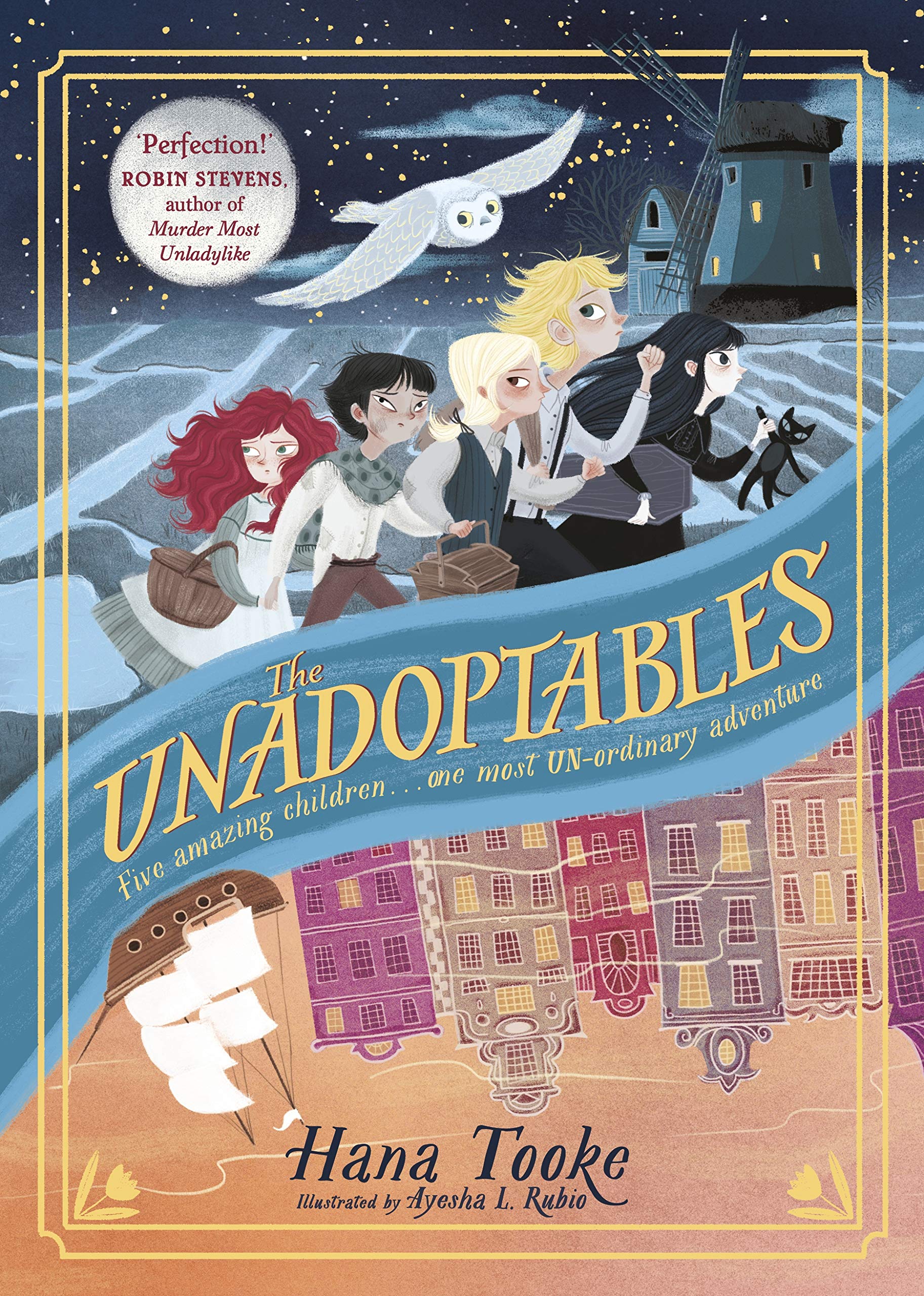

The first novel by émigré Hana Tooke is a sprawling adventure of five children—and it is already drawing lofty comparisons

Hana Tooke was in the final stretch of her MA at Bath Spa University, deep into a steampunk fantasy adventure manuscript, when she embarked on a completely new and unexpected middle-grade story. She was “in a tangle” with the work-in-progress, she tells me when we talk over coffee in a Bath café, when The Unadoptables crept up on her.

Tooke grew up in Holland, and had just returned from a trip there. “I was thinking back to my childhood and my identity and it felt like a lightning bolt. I woke up with most of the plot in my head.” With the support of her tutors, she shifted her focus to the new book. “A bit of a gamble,” she admits, but one that has evidently paid off. Within 48 hours of going out on submission, the book was snapped up by Puffin in a significant pre-empt deal. The publisher is already describing Tooke as a “heritage” author, and will publish in hardback in May.

The Unadoptables opens in the autumn of 1886 in Amsterdam. Five babies are abandoned at the Little Tulip Orphanage, each in curious circumstances. Twelve years later Milou, Lotta, Fenna, Sem and Egg have been deemed “the unadoptables”, until the night a sinister sea captain threatens to tear them apart and the gang make a daring escape. So begins a sweeping adventure, as the children pursue scraps of clues in search of the truth about Milou’s past. It’s a delicious mix of beautiful but accessible writing, thrilling action, a hint of magic, and unforgettable characters delivered with wit, wisdom and heart. Tooke is a natural storyteller with an enviably distinctive voice, and it’s easy to see why the book is attracting such attention.

It’s maybe a setting that readers haven’t seen before. The world-building always comes first in my ideas

The Dutch setting gives the novel a unique character. Tooke was drawn to the Victorian and Gothic, but wanted something less ubiquitous than London. “It’s maybe a setting that readers haven’t seen before. The world-building always comes first in my ideas,” she explains, here hooked around a series of images. “I had the windmill, I had Milou with her puppet, I had the orphans. I knew they were going to build a puppet father and I knew they were going to put on a puppet show.” She describes herself as a very visual writer, evident in the filmic quality of the book’s set pieces: the dramatic night-time escape from the orphanage; skating on a frozen canal; the magic of the puppet show. Then there are the rich little details that create such depth: a coffin-shaped baby basket; the clock-filled house of neighbour Edda; Fenna’s bond with a barn owl.

Child stars

Much of the book’s charm lies in its five child leads, but the ensemble cast did present challenges. In early drafts, the orphans were following Milou without questioning. “I had engineered it so all the plot points worked and I had to think hard about every single character’s motivation. Once I really came to know the characters, all the other issues I’d had came together.” Tooke also carefully considered the motivations of her villains, greedy orphanage matron Gassbeek and shipping merchant Rotman. Although both are gloriously grotesque, their actions are rooted in fact. The East India Trading Company really did take children from overcrowded orphanages with little expectation of their survival, the orphanage receiving “back pay” following their demise.

Even though now it feels like everyone is so much more accepting, there is still that undercurrent, and I think there are children who will identify with that, particularly after Brexit

In one of opening scenes, the orphans line up to be scrutinised for adoption. It’s a memorable moment which reveals how different each child is, from Milou with her graveyard pallor to six-fingered Lotta and selective mute Fenna. “All they have,” Tooke tells me, “is their weirdness in a world that doesn’t want it.” The process of writing proved equally revealing to Tooke herself. Aged 12, she moved from a very diverse school in Holland to rural Devon, and was keenly aware of “her accent and funny-sounding name”. This sense of difference stayed with her. Several drafts in she “realised that every single one of the Unadoptables was based, in part, on that period of my life”, echoed particularly in Milou’s yearning to belong. Tooke is keen to stress that this is not an overtly political book but she does hope it will resonate. “Even though now it feels like everyone is so much more accepting, there is still that undercurrent, and I think there are children who will identify with that, particularly after Brexit. Sometimes being yourself is a brave thing to do.”

Moving on

Tooke grew up north of Amsterdam, the child of an English father and Dutch mother. Her childhood was not particularly bookish, but it was very creative, full of woodwork, music and crafts. Echoes of the books she did love are imprinted into the pages of The Unadoptables: Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist (“I was obsessed from the age of three or four!”); Roald Dahl’s The Witches; and later Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. She was intensely imaginative and drawn to anything spooky: den-building and home-made ouija boards were a favourite pastime. “We would try to summon some ghosts and frighten each other with ghost stories.”

In adolescence “all my teenage angst went into songwriting”. The songwriting eventually expanded into fiction but it was in early motherhood that telling bedtime stories sparked the real compulsion to write. By this time Tooke was a primary school teacher, so she studied Bath Spa University’s MA in Writing for Young People over two years, alongside the day job. She describes the “amazing” course as a vital part of her writing journey, teaching her to draw sense and structure from “the chaos” of her ideas. The degree, led by Julia Green, has a prodigious reputation: Tooke’s entire workshop group are either published or about to be, including Nizrana Farook, Yasmi

Extract

Milou ran her fingers shakily over the co-ordinates. Things that were lost could be found again—if you knew where to look.

“I’m leaving!” she said, the words finally bursting from her lips. Four shocked faces turned to her. “This is a message from my parents—and, before you say anything, this isn’t one of my wild theories. This is proof. I’m going to find them. And I want you to come with me. Let’s leave this place together and never look back.”

“Milou,” Lotta said softly, despairingly,“we need papers. The only realistic way out is adoption and

no one except that horrid merchant wants to take us.”

Milou uncurled the watch’s chain and slipped it over her head, a plan already blossoming in her mind. Her Sense gently tickled her ears in encouragement.

“Then we’ll just have to adopt ourselves.”

Tooke now writes full-time, confessing that “I spend most of my time staring into the distance”. She is already deep into her second book for Puffin. It’s not a sequel, but it is set in the same world as The Unadoptables, in a different European city. Although she has felt the pressures of “second-book syndrome”, her delight at writing another book in this world is infectious. “I love the re-writing process,” she says. “The bit where I’ve got the shape of the story down and I can go and add all the nuance. That’s probably my favourite bit.”