You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

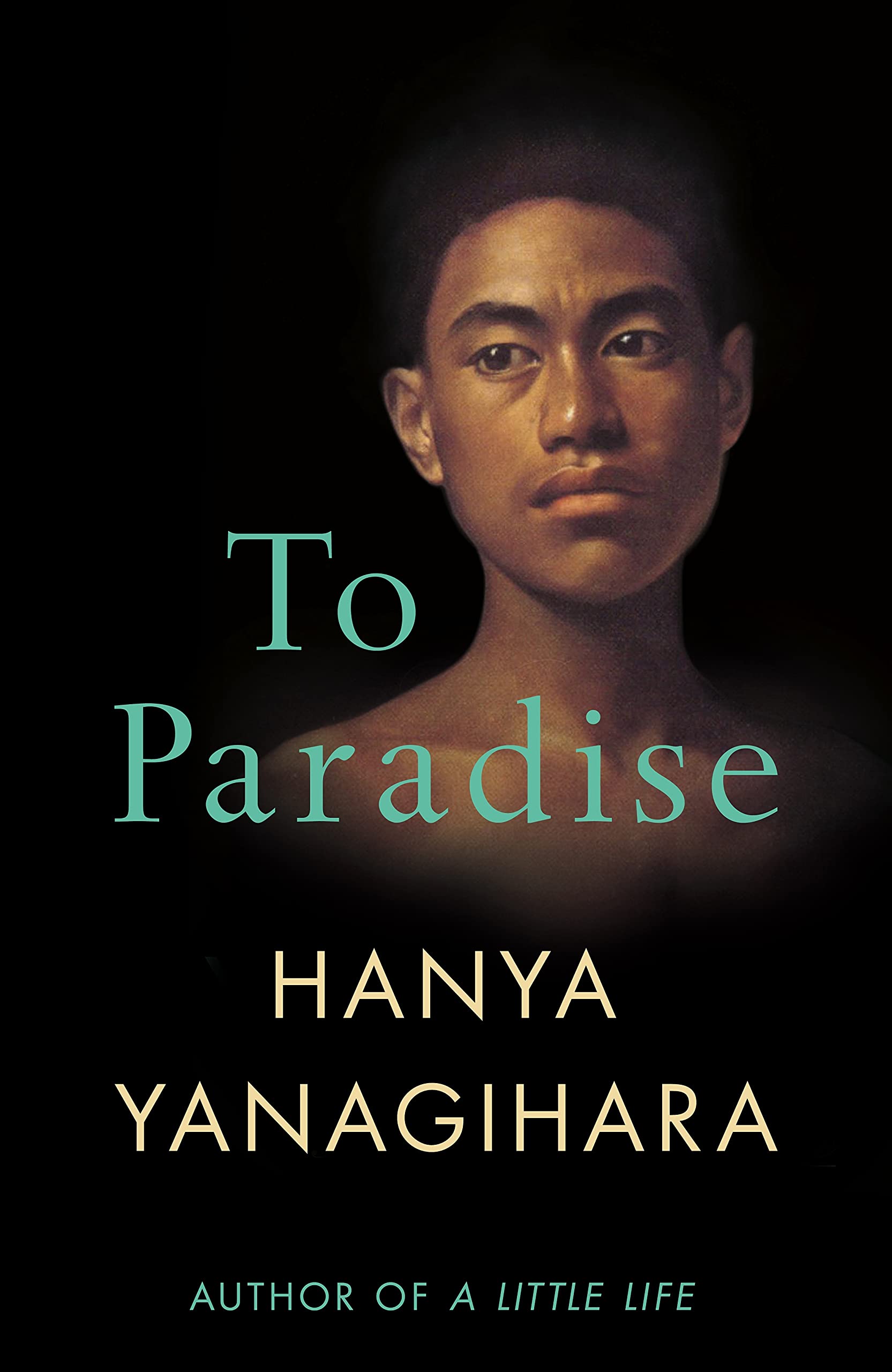

Hanya Yanagihara on her third novel, To Paradise

The eagerly anticipated third novel by Hanya Yanagihara envisions three different versions of America.

Back in 2015, Hanya Yanagihara’s second novel was published to little fanfare. Acquired for a modest advance, A Little Life became a huge word-of-mouth hit, selling well over quarter of a million copies in the UK; exceptional sales for a 720-page literary novel about a man haunted by childhood trauma.

Anticipation is therefore sky-high for her third novel, To Paradise, which promises to be one of the literary events of 2022. To Paradise is a powerfully imagined novel, composed of three books which explore three different versions of America, each a century apart: in an alternate 1893, in 1993 during the AIDS epidemic, and a future pandemic-struck world in 2093. When we meet in a central London hotel, Hanya Yanagihara, who lives in New York City, is composed but also warm and friendly, as she explains her initial interest in writing “about the conception of a what a country really is”.

It’s a fin de siècle book, it’s an end of history, end of century feeling and at the end of centuries we do feel that sort of collective uneasiness about what is awaiting us

She says: “It was the sense of possibility, of how easily America could have been something else, how easily it could become something else, that I wanted to explore in all three of these books. Because there have been certain moments in America’s creation, certain turning points where the country could have gone another way. So, in that sense [the novel is] not quite speculative and it’s not quite fantasy, but I’m interested in general in these sorts of hinge moments, in either personal history or national history, in which a choice is made that sets you barrelling down one course and a different choice could have meant something profoundly different.

“All three of the parts of this book are marked, I think, or identified by very personal stories against the background of much larger questions about national identity and what a nation must do, what it can do, what it should do and the very real consequences it has for these small individual lives within them.”

In contrast to A Little Life, which was set deliberately “out of time” with few orienting markers, Yanagihara says she wanted To Paradise “to be pegged very specifically to particular eras and to particular years within those eras. It’s a fin de siècle book, it’s an end of history, end of century feeling and at the end of centuries we do feel that sort of collective uneasiness about what is awaiting us.”

Book one opens in an alternate 1893, when New York is part of the Free States, a breakaway nation separate to the rest of America with certain freedoms available to its citizens. Gay marriage is permitted, and there is a tradition of arranged marriage among the families who settled the Free States, to create alliances and consolidate wealth. David Bingham is the restless scion of a rich family, whose grandfather wishes him to marry wealthy widower Charles Griffiths, but David is drawn to penniless music teacher Edward Bishop who may, or may not, be entirely who he claims to be.

The next section is set in 1993 New York, during the AIDS epidemic—although the condition is never mentioned by name—where another David Bingham, a young Hawaiian man, works as a paralegal and lives with his wealthy older lover Charles, a partner at the Midtown law firm where they both work. This David is hiding his troubled childhood in Hawaii, and the fate of his father.

The final part is set in 2093, when New York is now part of a totalitarian state in a world riven by pandemics. Outbreaks of disease are now so common they are referred to only by the year they first emerged. Rationing is enforced and it is illegal to grow food privately. Here lab worker Charlie’s story unfolds, in the first person, as she goes about her tightly delineated life and wonders where her husband disappears to in the evenings. Charlie’s narrative is intercut with letters written in 2043 by her grandfather, a powerful scientist, as he makes decisions that will directly affect the life of his beloved grandchild, whom he calls Little Cat. It is this section I found the most moving, not least because it speaks directly to our present situation and Covid-19. It seems remarkably prescient, although Yanagihara started thinking about the novel in 2016, before the US presidential election, and was researching it in 2017, long before coronavirus hit, writing around her demanding day job as editor-in-chief of T, the New York Times’ style magazine.

All in a name

One of the most striking, and at first slightly discombobulating aspects of the novel is that the same names—David, Charles and Edward—are used for different characters in each of the three sections. In 1892, David Bingham is a 28-year-old heir who once strolled around Europe on his Grand Tour whereas in 1993, David Bingham is a young man also known as “Kawika” (the Hawaiianisation of David).

“They are not meant to be the same people across centuries, nor living in the same America,” clarifies Yanagihara. “It was this idea of just taking the country

and turning it a half tweak on the dial each time. The people always had different selves, but the names themselves remain; just like the name of America remains for each generation, but America itself is something quite different.”

But the names of Bingham, Griffiths and Bishop do have a special significance: they are all names of famous missionary families from Hawaii, where Yanagihara’s parents grew up and she spent part of her childhood. “If you say these names to anyone in Hawaii, they know who they are. Depending on what tradition you come from, or which America you live in, you’ll see different connections—or not. If you’re not from Hawaii, and you’re not familiar with this missionary and colonialist past, I hope you will still be able to enjoy [the book] just the same.”

The relationship between a grandparent and a grandchild is a theme that recurs throughout the novel. Each of the three sections features a grandparent “who in various ways tries to control or help or guide or protect—and sometimes it’s the same movement under a different name—their grandchild’s future. In each case the grandparent makes a decision, always with good intentions I think, the consequences of which the grandchild has to live with or rebel against or accede to”, says Yanagihara. “This idea of being protected, of having someone look over you, to try to keep you from what they know of the world, and the very human reaction [of young people], which is to push against that, was something that I wanted to explore.”

Free to roam

All the characters, across the centuries, are grappling with what freedom means, and their own human needs and desires which are unchanging, despite their external circumstances. This is expressed most powerfully in the future section of the novel. Yanagihara says: “I want to show that, in what is clearly a totalitarian state, the concerns and the joy and the sorrows of the individual in that state do remain. Charlie is living in what is clearly an awful place but what she wants most of all is not freedom, but to be loved.”

Later, she adds: “The world that Charlie lives in, [a world] that is totalitarian and unpleasant, will not be a permanent state of affairs. At some point something will change and the country itself will change and I think that is something that all of us have learned, that the state of a country, the state of a culture, is ever-shifting and ever-changing.”

Later, she adds: “The world that Charlie lives in, [a world] that is totalitarian and unpleasant, will not be a permanent state of affairs. At some point something will change and the country itself will change and I think that is something that all of us have learned, that the state of a country, the state of a culture, is ever-shifting and ever-changing.”