You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

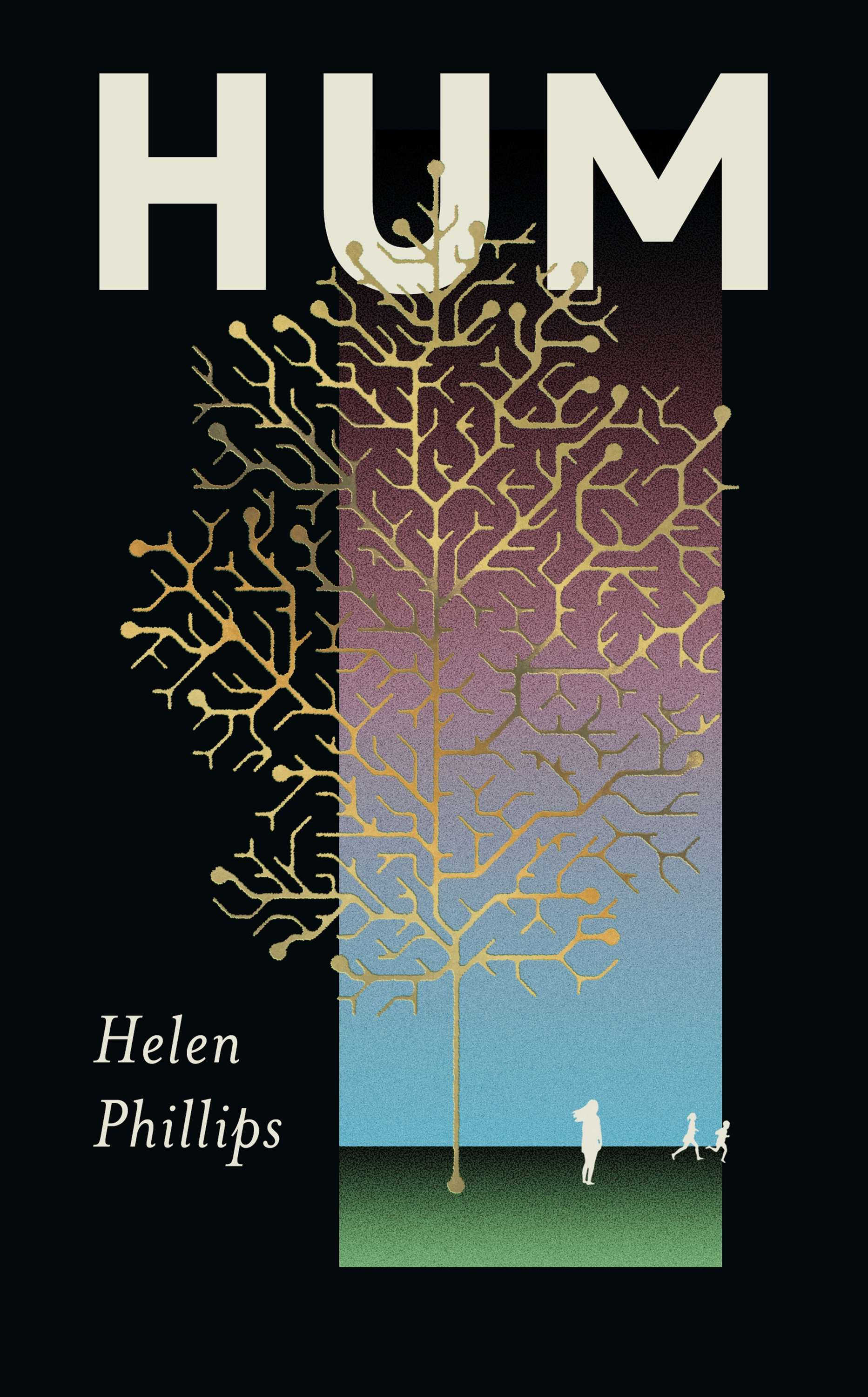

Helen Phillips' timely new novel explores motherhood and family in a dystopian world ruled by technology

Katie Fraser is the chair of the YA Book Prize and staff writer at The Bookseller. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International

...moreHum depicts a mother-of-two who is struggling to make ends meet in a dystopian society riddled with surveillance

There are 68 points on the human face that “make our face print”, says Helen Phillips over video call from her home in Brooklyn, New York. Facial recognition software uses these areas to identify individuals—but what happens when these coordinates are altered? Phillips’ svelte and timely novel Hum asks such a question.

In a dystopian future where society is riddled with surveillance and nature is worryingly absent, mother-of-two May has been pushed to her limit: she is unemployed, and both she and her partner, Jem, are struggling to make ends meet. Desperate to make money, May agrees to an experimental surgery to have her face altered in return for a fee. The procedure is performed by a “hum”, one of many super-intelligent AI robots that now populate the earth. Not only have hums displaced many people from their jobs—May included—they are also walking-talking billboards. Every few minutes a hum will unleash a new advertisement unless you pay for ad-free time.

Part of the procedure involves moving a needle across May’s eyelids—an experience inspired by Phillips’ own. When she was 11 years old, Phillips lost all her hair due to alopecia: “I was 13 or 14 years old, and my mom and I decided that I should get eyebrows and eyeliner tattooed on. That experience of lying down and having a needle so close to your eyes—on a physiological level, that’s where the beginning of the book comes from.” In an essay published in a national newspaper, Phillips described the experience as “torturous”.

Now with a healthy bank balance, May purchases a family trip to the Botanical Garden, a walled-off green sanctuary to which only the rich can afford entry. Eager to connect with her family and for her children, Sy and Lu, to experience nature, unfettered by concrete and technology, May bans the use of phones and “bunnies”, a gadget akin to a children’s smart watch. In the gardens, everything appears bucolic, but cameras lurk beneath the foliage and May’s tech-free decision leads to a potentially dangerous situation.

As a writer and a mother, I was on a quest for hope while writing Hum... How do you forge connection in this future that we seem to be creating?

It “did not even take much imagination” to build the world of Hum. Our world is already progressing in a direction that rewards digital connection over physical intimacy. While writing the novel, Phillips “was very interested” in Margaret Atwood’s comment on The Handmaid’s Tale: “One of my rules was that I would not put any events into the book that had not already happened.” The statement has “fascinated and haunted” Phillips. “We are not yet in the world of Hum, but there are elements that are quite similar.”

Hum is equipped with extensive endnotes that provide chilling reading, detailing the astounding amount of research Phillips undertook to ground the novel in real-world events. For example, Sy’s comment on the disrupted hibernation patterns of black bears is from David Wallace-Wells’ The Unhabitable Earth. In chapter one, Phillips cites Carl Zimmer’s work when she writes that the number of birds in North America has declined by three billion in 50 years. Her research has built a dystopia that not only presents a reality that is distinctly possible, but one that is already happening.

However, there is hope. “I think that May is on a quest for hope and I, as a writer and as a mother, was on a quest for hope while I was working on it,” says Phillips. Although Phillips describes Hum as “more science fiction” than anything she has written before, it is not “pure dystopia” as the author “felt like it was almost irresponsible to use my imagination in that way”. And so, the novel asks: “How do you forge connection in this future that we seem to be creating?” The first step is focusing on interpersonal relationships. In Hum, society is “bent against” physical intimacy and connection, but May is “in search of physical experience” and the interplay between “technology and the physiological is absolutely integral to the book”.

Phillips’ prose is concerned with embodied experience. The chapters are dappled with tender descriptions of the family, from how Jem cups May’s face to how the children move, sleep and play in the gardens and streets. Phillips wanted Hum to explore “what it means to have a physical body and an embodied experience. And a body, in all its weakness and strength, in a world that is ever more automated”. She continues: “I do think that there are so many talking points in the book about AI, climate change and surveillance, and those things are of great interest to me—but it was always a story about a family.”

When I liken May to a vigilante, the description appears to sit well with Phillips. “I love the idea that she’s sort of a vigilante, but I will say that having children now, in this world of screens, you have to be a vigilante if you want to help shape their minds in a healthy way.” Phillips, also the mother of two, is acutely aware of the digital cost–benefit analysis. “You have to be on your toes just to make sure that they’re also doing healthy things with their bodies in the world, and with their friendships in the real world.”

May’s conflict with her children over their bunnies is not unlike a similar dilemma Phillips has faced. “My daughter, who was 10 years old at the time, really wanted to start to walk a mile to and from school,” recounts Phillips. “The compromise we came to is that she could walk on her own, because her independence is important to me, as long as she had a watch that I could track her with. This was [happening] right as I was writing this book.”

The irony is not lost on Phillips, but the situation represents the “grey area of tech” Hum examines. By exploring this, the narrative asks “what it means to be a mother and what it means to provide comfort” in a world where embodied experience must now compete in the same space as digital tools. Crucially, the story does not take a “moral position” on the use of technology; instead, readers should take their cue from the novel’s epigraph, a quote from Paracelsus: “Poison is in everything, and no thing is without poison. The dosage makes it either a poison or a remedy.”

Although the Renaissance polymath was not referencing smart phones, Phillips believes it is a “profound statement about technology”. She adds: “Can we throw all of our technology in the ocean and

be done with the world we have created? No.” The choice is about how we use technology and where we give our finite attention. “We need to guard our attention more preciously,” says Phillips, and decide whether to bestow it on the people and the world around us or to the phones in our hands.