You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Hernan Diaz, the historical silencing of women, boundaries of trust and his fascination with the American individual

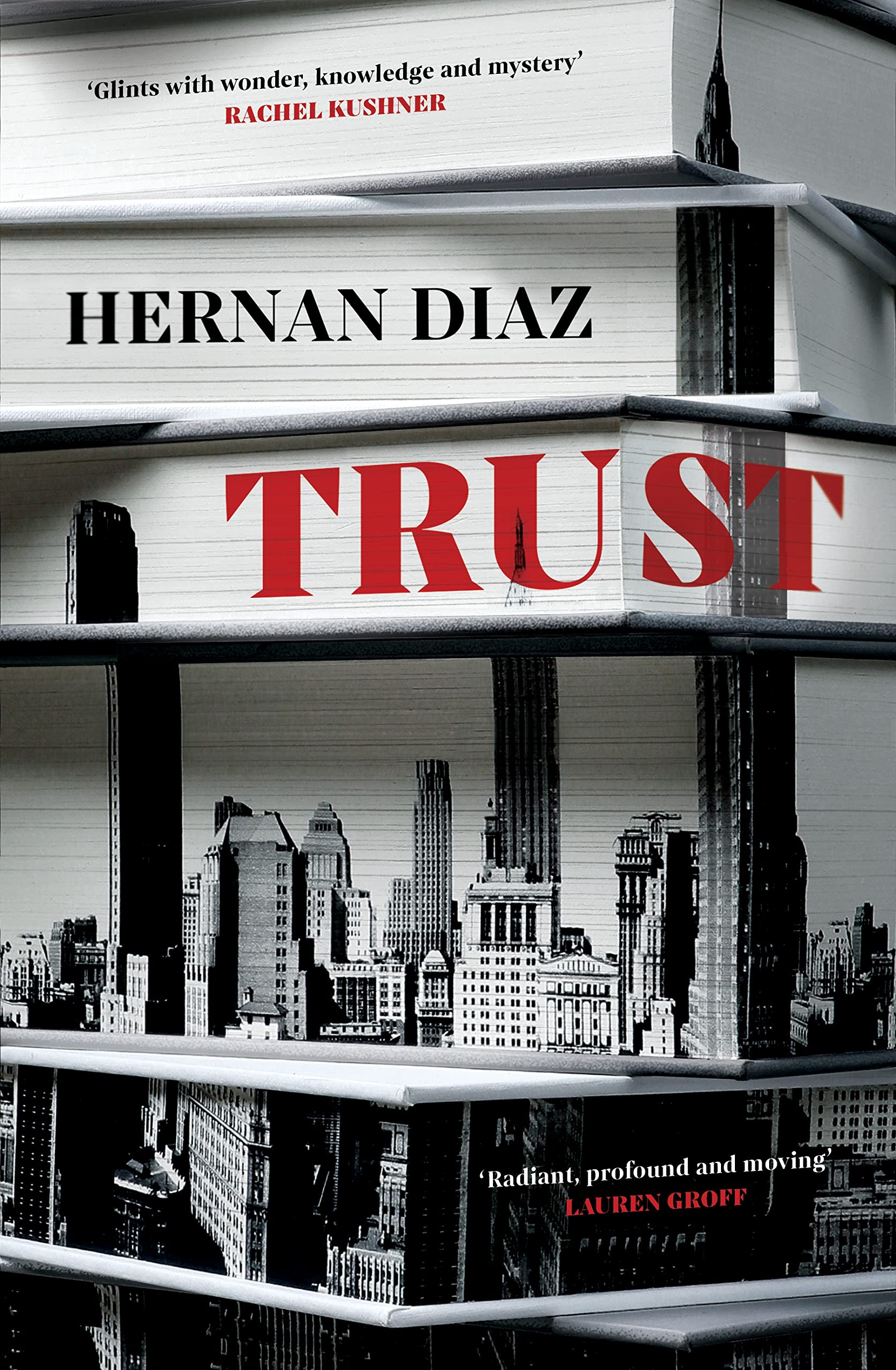

An international rights sensation, Hernan Diaz’s second novel Trust is a literary puzzle which explores wealth, capitalism and who exactly gets to tell the story.

Hernan Diaz’s clever and intriguing second novel, Trust, is divided into four segments, the relationship between which readers must figure out as they go along. The first section presents as a novel written in the 1930s by one Harold Vanner, exploring the life and career of a great New York financier: Benjamin Rask, a man with a consuming passion for capital and the movements of capital, a feted figure on the financial markets whose status becomes legendary. It also tells of his reserved, singular wife Helen who, after marriage, devotes herself to using her husband’s fortune for philanthropy to the arts, but following the great stock market crash of 1929, succumbs to a mental illness which leads to her death.

This novel-within-a-novel is hugely engaging but relatively short. A second document follows: the bombastic autobiography of Andrew Bevel, a financier whose life appears to echo that of Rask, and who is keen to make clear that in his glittering career the pursuit of profit was always aligned to the social good. He also wants to put the record straight on the fate of his beloved wife Mildred, whom he lost too young. Yet the memoir is only half-written, with notes here and there on how to build the story out, visible in the text. What kind of narrative is it?

Two further segments then follow, both documents authored by women involved in the financier’s story, either as visible players, or hidden hands in the background; these cast further light—and shadow—on the nature of the story being revealed.

I feel that in American fiction, money is already made: there are very few novels about money-making itself, and to me that was very interesting and another erasure—an eloquent silence

Over the line from Stockholm, where Diaz is visiting (his background encompasses Argentina, Sweden, the UK and the US, and he is an academic at Colombia University in New York) the writer explains how he came to be drawn to the recurring myth of the great American wealth-creator. “There’s a certain idea that has to do with the place of the individual in the American imagination and how individuality is fetishised in the United States, which to me is very remarkable,” he explains. “This myth of the individual against nature, against institutions, against fellow human beings, is such a distinct feature of American culture to this day. This ‘great individual’ idea is highly gendered—it’s always a great businessman and a self-made man; that to me was utterly fascinating, how women have been completely erased from the great narratives of capitalism.”

He was also intrigued by the fact that although money has an “almost transcendental and mythical” place in the American imagination, very few novels are actually about money itself—as though it exists in some kind of blind spot, or is taboo. “In American fiction there are a lot of novels about class, or novels of manners, and novels about the eccentricities of being wealthy, or about exploitation. All of that exists, but I see that as American literature showing the symptoms of money. I feel that in American fiction, money is already made: there are very few novels about money-making itself, and to me that was very interesting and another erasure—an eloquent silence.”

Capital gains

In Trust, Diaz tackles the topic of money-making head on, with a light, literary touch, as Rask and Bevel execute their dizzying financial coups, riding and orchestrating the movements of the stock markets, boosting their fortunes as the markets collapse around them. Rask sees finance almost as an art: “He was fascinated,” writes Vanner, “by the contortions of money—how it could be made to bend back upon itself to be force-fed its own body.”

Diaz explains: “I thought that he would be an aesthete of money, almost questioning the instrumental, practical dimension. This was why I was interested in finance capital rather than an industrialist or someone who manufactures goods—there’s this circular thing of capital begetting capital begetting capital, which to me is an increasing realm of abstraction. It shows how finance capital is divorced from social value. It doesn’t create any social value and yet it rules all our lives.”

In his research for the novel, he worked almost entirely with primary sources from the early 20th century—newspapers and journals from the time, personal papers, or records from the congressional hearings that took place after the 1929 crash. “That already gave it a slant that was much more interesting, I was dealing with literary matters such as tone and register and a certain flavour of language that I wouldn’t have found otherwise.”

Wealth, like a black hole, has this enormous mass and an event arises around which things start to bend. Time behaves differently, social relationships are distorted and our perception is really warped as well

He also looked at the personal diaries of the wives of the financiers of the day. “Two things struck me: the first one was seeing how these women had been pushed into these roles as social accessories, I found mostly lunch plans, guest lists, gift lists, all the constraints of their very limited social lives, and I felt a sense of suffocation there. You read a diary and the entries say: ‘At home... At home...At home...’ A lot of it went into the novel.

“The most eloquent thing that I found there was, I would request these archival boxes that would be brought to me by the curators, and miscellaneous papers come in little parcels tied up with twine. I would undo the twine, and it would leave this cross mark [on the paper], meaning they have been sitting there untouched for 90 years and nobody has cared to look at them in almost a century. That speaks again to the silencing of these women.”

Later in the book, we learn of the monumental mansion Revel builds for himself; inside his offices it is so cool and quiet, as though the hustle and bustle of New York under construction outside barely exists. Diaz is interested, he says, in how wealth can seem to bend and realign reality: “Part of the inspiration for that was personal experience—whenever I happened to be around great wealth, I found myself, to my dismay and embarrassment, behaving differently. If you visit a certain friend who is terribly wealthy, you tread more carefully, speak more softly; I thought, ‘That is curious, I hate that it happens to me but it does’. I extrapolate that out to societies—wealth, like a black hole, has this enormous mass and an event arises around which things start to bend. Time behaves differently, social relationships are distorted and our perception is really warped as well. This to me was endlessly fascinating. And so much of the book was written during the Trump administration, where it seemed to me that reality had been commodified, it was up for grabs, the ultimate luxury good.”

We expect certain documents to be more robustly anchored in truth—such as a historical document—whereas when we read a novel, the text is excused from being tied closely to truth

Diaz is looking, he says, for a critical reader, a reader who will act as a detective in the story, looking for clues in the documents laid out before them to pick out where the narrative is taking them. That relates, too, to the title, Trust. “We walk into a text and we agree to certain terms and conditions even if we’re not cognisant of this fact,” the author muses. “We expect certain documents to be more robustly anchored in truth—such as a historical document—whereas when we read a novel, the text is excused from being tied closely to truth."

“I think both of those things that I just said are false. Obviously there are many ideological falsehoods in history and obviously literature has been, at least for a couple of millennia, perfectly able to convey part of the truth of what it means to be a human being on this planet. So I was hoping that as the reader makes his or her way through the book, they would question the pre-assumptions they had for each section as they moved forward; read against the grain.”