You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Hisham Matar in conversation about his novel about three Libyan friends in exile

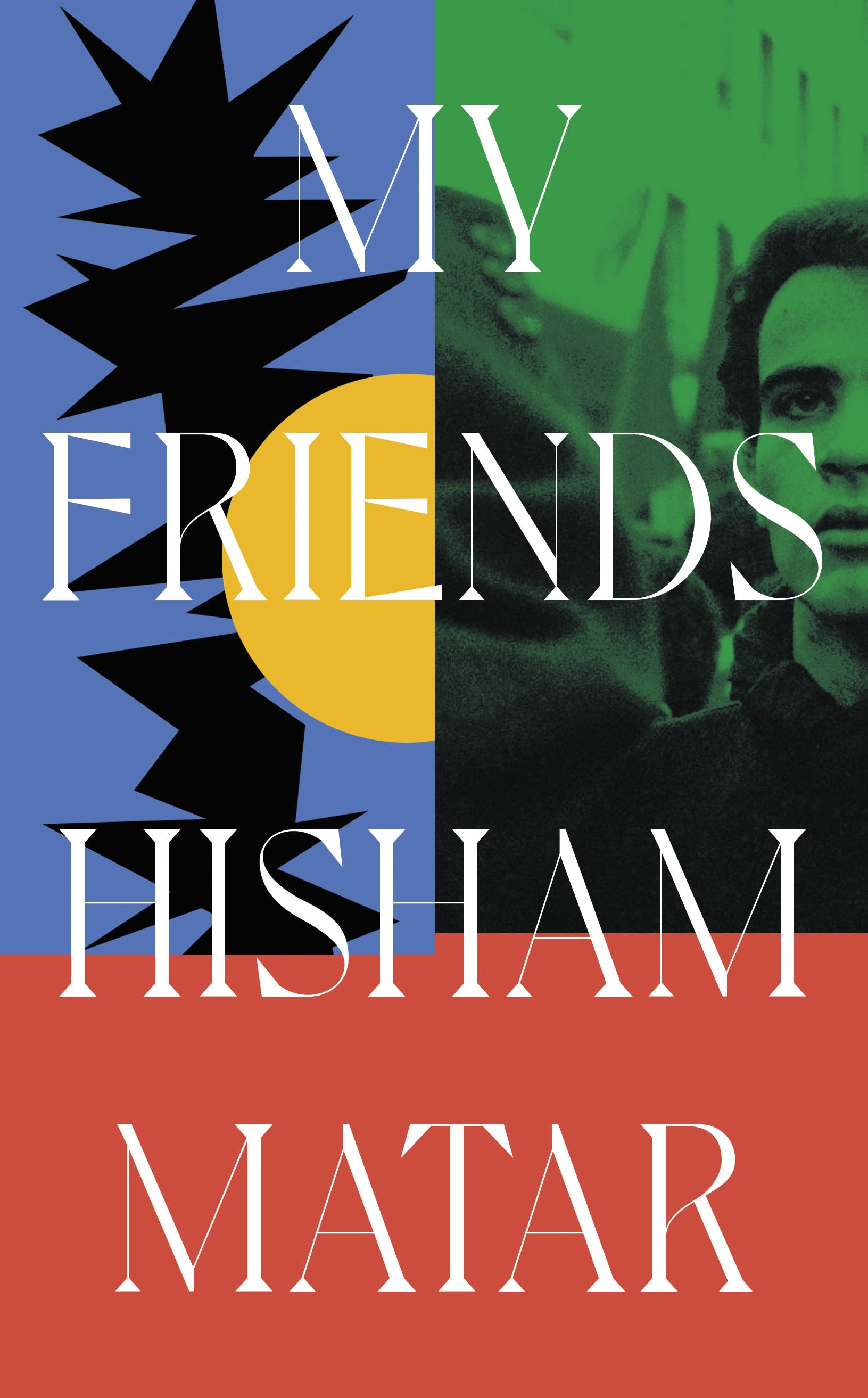

My Friends, the extraordinary third novel from Hisham Matar, is the story of three Libyan friends in exile.

"I wanted the novel to open with a parting because I think whenever you take somebody that you love to an airport, or train station or wherever, the world seems to completely change the moment they leave. I thought that would be a very good place to start because in a sense a novel is a departure, it is a setting off.” My Friends, the extraordinary third novel from Hisham Matar, is the story of three Libyan friends in exile. The story is told across a walk in London, from St Pancras to Shepherd’s Bush, on one day in November 2016, after the narrator, Khaled, says goodbye to his old friend of two decades, Hosam, at the station and walks back home.

It is a walk of a few hours, and yet it spans decades, as Khaled revisits his past. Born and raised in Libya, he leaves in the early 1980s to attend university in Edinburgh as an 18-year-old student on a government scholarship, expecting to return home to his family after graduation. But when news comes of students rounded up and thrown in jail by the authorities back in Libya, Khaled and his friend Mustafa decide to travel to London to join a demonstration in front of the Libyan Embassy.

All along, everything I wrote, I felt I wrote at the expense of this book

This is the precise moment that Khaled’s life is wrenched from its predictable course. When officials inside the embassy open fire on the peaceful crowd outside, Khaled first hears the sound of the bullets as

“a series of tears like the wind ripping sails”. And then: “It literally pressed into me and then ran through me with unremitting force, unquestionable, until it reached the centre of my brain and halted there for a moment before turning back and scorching outwards, pushing with it everything that I was, everything that I did not even know I was, to the outer limits. I was now empty and standing, my life reduced to a single unbroken line of a swirl locked inside a child’s glass marble. And there it rolled out, that marble, rolled out of me, taking everything with it,” Matar writes. The scene, a searing 13 pages that culminates in the reaction of a young hospital doctor when he sees the extent of Khaled’s injuries, is devastatingly powerful.

The embassy moment

The Libyan Embassy shooting, which is the defining event of Khaled’s life, was a real event, of course. On 17th April 1984, 11 demonstrators were wounded and a young policewoman, Yvonne Fletcher, was murdered. When we meet in a pub in west London, I ask Hisham Matar about the challenge of interweaving real events with fictional characters. “I was very ambivalent about it for a while. I thought, maybe this is not the thing to do but it really just imposed itself on the narrative.”

It was another brazen attack by the dictatorship on civilians, but it was also happening in public, the international public, and others were affected by it

He remembers watching it on the news at the time, seeing the demonstrators on the ground, screaming. One was calling out for his mother. Matar was 13 years old and that image “never left me”, he says.

“Years and years” later, he became friends with two people whom he later discovered had been at the demonstration and had been shot. “It was through them, without necessarily wanting to know, I’ve learnt a lot about it, even though I wasn’t there.” When Matar realised he was going to write about it in the novel, one friend was “very generous” in talking about the experience in detail.

After Matar finished the novel, he invited his friend over for dinner and, full of trepidation, read the section aloud. “I was worried he would feel dispossessed of this experience, but I looked up after I read it and found his eyes were all red. He thanked me exactly for the thing I was worried he would be offended by. He said, ‘Thank you for taking something that happened to me and making something else of it, something different of it.’

“I think a lot of people who were there, and I suspect people who were not there—Libyans I mean—felt this strange contradiction. It was another brazen attack by the dictatorship on civilians, but it was also happening in public, the international public, and others were affected by it. I don’t think anybody knows how to talk about it, you know, really. And I think maybe those are the things to write about—when there isn’t a way to talk about it.”

Khaled survives but his life is forever changed. Having fallen foul of Colonel Qaddafi’s government he knows that he cannot return to Libya, it is not even safe to return to his studies in Edinburgh. In the immediate aftermath of the trauma, a Lebanese friend, Rana, saves him by letting him stay in her parents’ empty flat in London: “My ears were underwater and her voice a helicopter above”, Matar writes. Over the years that follow, Khaled, Mustafa and their friend Hosam, a writer, must live in exile, separated from their families but sustained by their—sometimes very complicated—friendship, until politics shift again, with revolution in Libya and the death of Qaddafi.

I think that books themselves have their own time and they oblige you, as a writer, to write them in the time they need to be written

Qaddafi is mentioned by name perhaps a handful of times, but his presence permeates the novel. Matar had been thinking about the novel since the Arab Spring in 2011—although he recently found a note from 2003 with an idea for a book about friends in exile “and the emotional country that certain deep friendships can provide”—and by 2014 he had a sense of how to proceed. He started work on My Friends, only to break off and write The Return, his 2017 Pulitzer Prize and Rathbones Folio Prize-winning memoir which documented his journey to Libya to discover what happened to his activist father, who was kidnapped and imprisoned by the Qaddafi government. Having found no trace of his father, and grieving, he made a trip to Italy to find solace in the paintings of the Sienese school, out of which came another memoir, A Month in Siena. Now, he says, “All along, everything I wrote, I felt I wrote at the expense of this book.

“Books exist in time in the obvious sense, they have their own temporal structure, we read them against the clock— how many pages, how long did it take you to read this—but I think that books themselves have their own time and they oblige you, as a writer, to write them in the time they need to be written. I couldn’t have written this earlier… I wouldn’t have been able to write about Qaddafi back then. It was just too close.”

Matar says of his first three books—the novels In the Country of Men, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, Anatomy of a Disappearance, and the memoir The Return—that “each is very different from the other, but they are all dealing with fathers and sons and with the very simple fact that you are born into consequence, and you are an inheritor of the aftermath of things and you have to somehow figure out how to deal with that. But this, I feel, is a book about contemporaries.”