You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

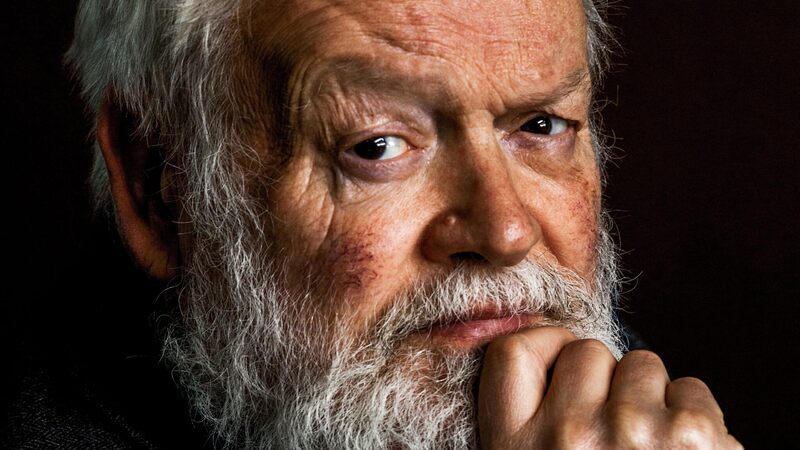

Justin Cartwright: The human impulse

Newly returned from a visit to Namibia, Justin Cartwright may be sitting in the Groucho, but he still has the red dust of Africa on his shoes. The Whitbread Book Award-winning novelist (Leading the Cheers, 1998) has lived in England for all of his adult life, but he remains a frequent visitor to the continent where he was born, usually in his capacity as a TV film-maker. "I am still terribly interested," he says. "Doris Lessing once told me she rings Zimbabwe every day to see what the weather's like; I'm not that bad, but I do keep up an interest in the politics."

Cartwright's latest novel, White Lightning (August 15th, £16.99, 0340821744), has, for the first time in his work, a South African setting. He was interested, he says, in the formative effect of its landscape: "I'm much more European, but there's no question that in some strange way we conform to our landscape; it does enter you in indelible ways. The people do too."

White Lightning is a first-person narrative: the protagonist is James, a once ambitious film-maker whose career has descended into a soul-numbing, if often comically observed, round of corporate videos and soft-porn. He returns from London to his childhood home in South Africa, now in the post-apartheid years, to be by the bedside of his mother, who is slowly dying.

During the quiet days of her final coma, James re-evaluates his life: retrospective episodes from London--including a desultory relationship with Ulla, a porn film body-double, and the sudden death of his own young son from asthma--contrast with what appears to be the opportunity of a new beginning. It turns out that James' mother will shortly be bequeathing him a previously unimagined small fortune: perhaps, the reader infers, there will be a chance for the first time in James' life for him to do something generous, something redemptive.

He has no interest in the politics of the new South Africa, but by chance he befriends a destitute young Xhosa boy with HIV, and decides to pay for his medical treament. He also offers Piet, a caged and long neglected baboon, the creature's first taste of companionship and of freedom. These new hopes are shortlived, however; as the novel progresses further, it becomes clear that there are going to be no simple resolutions or clean slates for James--any more than, perhaps, for the country itself.

"I know it sounds pretentious, but what I was trying to do was to write a novel about the human condition--although I hope that's not too obvious in the book," says Cartwright. "It's about really what it is to be a human being; I've tried rather scrupulously to take these few weeks in the life of this man whose mother is dying, and who has reached a kind of crossroads, and to look very closely at every juncture at how I imagine a person like this would have reacted. Life doesn't necessarily have any meaning, but it certainly has these deeper impulses, which to me are the most interesting."

Cartwright's cool and unflinching eye upon his compromised main character's motivations left him, as he puts it, "walking a tightrope" in the novel: "I didn't give myself any cop-outs but I did make him aware of his own failings. I tend to feel more comfortable, in a funny way, with a slightly ironic, sceptical tone--but, that said, I don't think it's unenthusiastic."

It is important for him, he says, that there be an absolute truthfulness to his prose. "What I can't bear is when I read a paragraph that seems too easy to me; the analogies are too obvious, the metaphors and the similes. I've often been asked about the British novel--'Is it vibrant? Is it moribund?'--and I think one of the things I would say is that it isn't worked enough. I tried not to have any false notes in the novel."

James' growing attachment to the baboon Piet is a crucial element in White Lightning. Cartwright, who once encountered a man so affected by the death of his pet baboon that two years after its death he was unable to talk about it, is curious about what a love of animals involves: "I think it's a sort of displacement. We don't have a chance of idealistic expression, yet we do have these impulses that are frustrated elsewhere."

But optimism for the human project, it seems by the end of the novel, is misplaced. Cartwright observes that "there is a level of evil and disappointment that never goes away; it is a strange preoccupation of ours that it is going to change." Yet there can still be a tender regard for human vulnerabilities. Without preamble, Cartwright offers up an anecdote: "There's a guy in my park who says, 'Time goes quick, dunnit?' That's all he says. Sometimes I say, 'Good morning', to see what he'll say. He always says, 'Time goes quick'. He's a slightly tragic figure."

Benedicte Page

Previous UK trade sales*

lLeading the Cheers (1998): 50,000

lHalf in Love (2001): 30,000

*Source: Sceptre.