You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

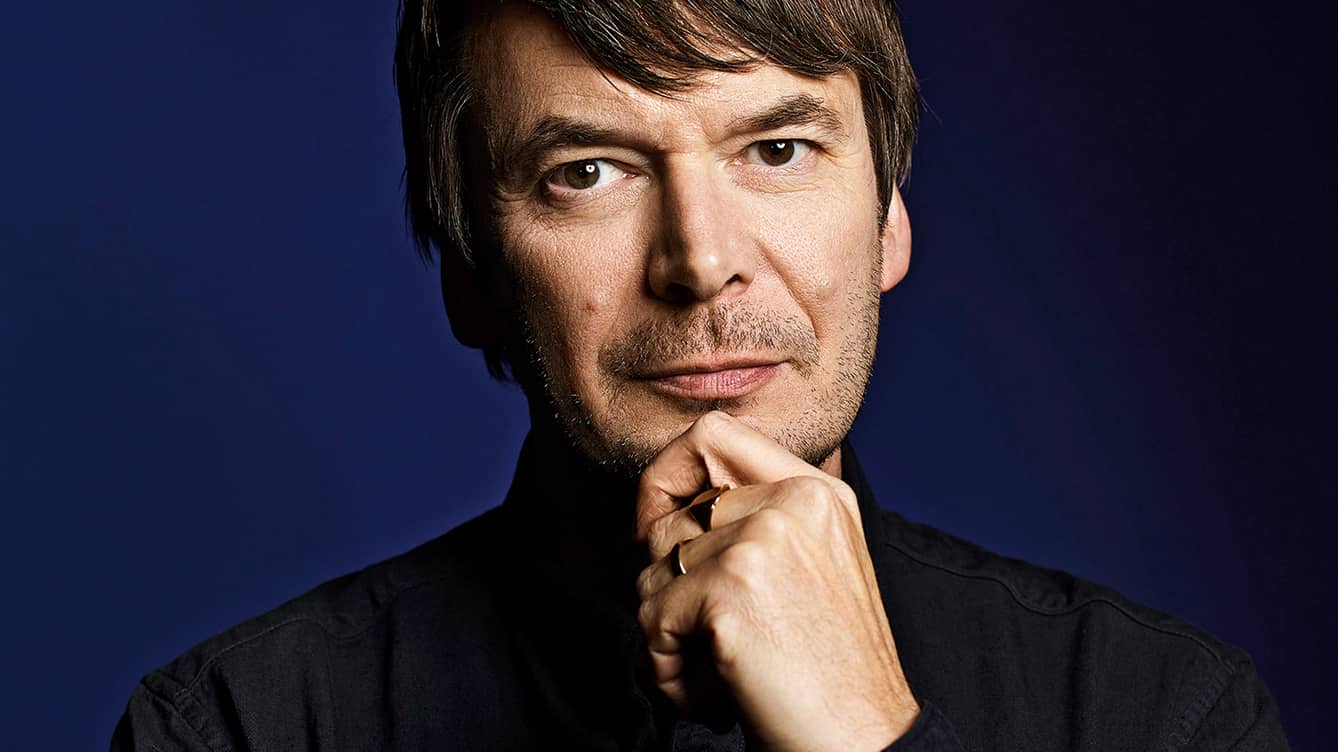

Ian Rankin | 'I would like a new generation of readers to come to the works of William McIlvanney'

Ian Rankin talks to us about his latest case, The Dark Remains, which sees him revive the late William McIlvanney’s sleuth Jack Laidlaw.

When Ian Rankin was a PhD student and working on what would become his first Rebus novel, instead of writing his Muriel Spark dissertation, he went to an event at the Edinburgh Book Festival featuring William McIlvanney. Rankin was a fan, particularly of McIlvanney’s three Jack Laidlaw books, the hard-boiled crime trilogy commonly cited as the foundation stones of Tartan Noir. After the talk, Rankin went to get his book signed and “I sort of blurted out to him that I was writing a novel kind of like the Laidlaws, but set in Edinburgh. So when he signed my copy, it said: ‘Good luck with the Edinburgh Laidlaw’.”

Those Edinburgh Laidlaws, of course, saw Rankin become the biggest star of Scottish and arguably British contemporary crime writing. He and McIlvanney remained friendly, reuniting at a Glasgow event for 1997’s Black and Blue—the eighth Rebus but the first that truly broke out—and meeting up at various book festivals and fairs over the years, until McIlvanney’s death six years ago.

Willie’s style is more rococo, more poetic than mine. And Laidlaw is set in Glasgow in the 1970s, which is obviously very different than the world I inhabit

In the Noughties, though, it would be fair to say McIlvanney’s star, at least as a crime author, was on the wane. His last Laidlaw, Strange Loyalties, had been published in 1991 and as McIlvanney turned to poetry and general novels, the trilogy—despite being lauded by the new generation of Scottish crime writers as an inspiration—went out of print. We should note, however, that McIlvanney had some serious non-crime writing chops: his début, Remedy is None, won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, while 1975’s Docherty bagged the Whitbread Award (now the Costa). But in 2013, Canongate re-released the Laidlaw books, opening them up to a huge new audience.

Rankin says: “It was thrilling to see that resurgence of interest, because all the Scottish crime authors used to reference him but he had almost been forgotten about by readers as a crime writer. So when they came back into print, all these people got to see how wonderful he was. I think he was genuinely buoyed up by it. I was interviewing him on the stage at Theakston Crime Festival at Harrogate a couple of years before he died. It was early on a Sunday morning and we were walking to the hall and he said, ‘Who’s going to come to see me, Ian? No one knows who I am.’ Now, that main hall at Harrogate holds maybe 800 and it was packed, standing-room only. And his face just lit up. It was lovely for him to have that second act, as it were, after being off the stage for so long.”

Rankin is now trying to help McIlvanney have a third act. Last year, he was asked by Canongate publishing director Francis Bickmore and McIlvanney’s widow, Siobhan Lynch, to look through around 100 pages of notes the late author left behind for a Laidlaw prequel, in order to see if there was enough there for a book. The notes were not exactly straightforward: they weren’t just for a new Laidlaw, but also for another novel, plus some personal reflections and thoughts on politics.

Rankin says: “I said to Francis, ‘If you did X, Y and Z you could get a book out of this.’ He said, ‘Great, because Siobhan wants to know if you would give it a go.’ I took a sharp intake of breath. For a lot of reasons. Willie’s style is more rococo, more poetic than mine. And Laidlaw is set in Glasgow in the 1970s, which is obviously very differ- ent than the world I inhabit. I knew it was going to be a challenge, but I said I would try to see if I could mimic his voice, because I didn’t want anybody to see or hear me. I wanted it to be Willie’s style, his philosophy, his voice.”

He read and re-read the Laidlaws to try to get the tone right, and there was a quite a bit of research about Glasgow in the 1970s, from how the city looked and felt, to some more mundane things: Rankin figured out that the book should be set in October 1972, as McIlvanney sketched out a scene in which “The Godfather” was playing at the cinema. And, some more-than-mundane facts: “Well, Willie didn’t really lay out who the killer was in the notes, which is sort of important in a crime novel. I mean, I could feel that he knew who the killer was, but I had to deduce it from everything else he had written. So, yeah, it was a challenge, but it kept me busy during lockdown.”

The final product, The Dark Remains, starts as a lawyer, who is linked with an organised crime gang, is found murdered behind a pub, in a rival gang’s territory. Enter young detective Laidlaw, new-ish to the police but just as troublesome to his bosses as he is in the original trilogy. An older cop takes Laidlaw under his wing, and the two are plunged into the investigation as they not only try to find the lawyer’s murderer, but to stop a gangland war from breaking out.

Rankin says: “It took a fair bit of work, a fair bit of editing and to-ing and fro-ing. But the nicest thing was that when Siobhan read it, she wrote me a lovely handwritten letter to say that she couldn’t see the joins; where it stopped being Willie instead of being me. Which was nice. So that meant the act of ventriloquism worked. So, that’s half the job done. But the other half is the real reason I took this on: I would like a new generation of readers to come to the works of William McIlvanney.”

Young Rebus

Perhaps the obvious question is, after Rankin passes on, would he mind others taking on the Rebus mantle? “Well, I guess I wouldn’t be bothered that much because I wouldn’t be around to have any say. Maybe it’s inevitable, as these days if you have a good saleable character or a brand, they can live long past the death of their creator. I’ve always thought maybe someone could come along and do a young Rebus, like young Morse in ‘Endeavour’. I’ve thought about doing it myself, but that would be Rebus in the 1970s and ’80s, which means a historical novel, and I used to think that would be too much work. But maybe [The Dark Remains] has whetted my appetite for doing a young Rebus.”

For the day job, Rankin is currently working on “a lot of hush-hush television stuff”. His next book for his usual publisher Orion will be a standalone, of which he is at the very early stages—“I gave my agent about a 20-word synopsis, and he said, ‘Yeah that sounds fine’—so he reckons the next Rebus novel won’t be out until 2023. He ages Rebus, meaning the now-retired Edinburgh cop turned private detective (of sorts) will be knocking on 70 in the next instalment.

“I’ve enjoyed the ageing process,” Rankin says. “He’s not the same guy as I was writing about five years ago, so that makes it fresh, keeps me on my toes. I always say it and I’m going to say it again, I can only see one more Rebus book. I can never see further ahead than one book and I might have said it was the last Rebus seven or eight times in the past. But every time I’ve said that something has come along that has suggested itself as a theme or a story where he is the ideal character. So it seems he always has that wee bit of life left and he just refuses to leave the building.”