You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Deborah Orr | 'The more humble my beginnings, the more I appeared to have achieved'

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson worked as a Waterstones bookseller, and as a book publicist before becoming a freelance writer in 1997. The Bookseller’s

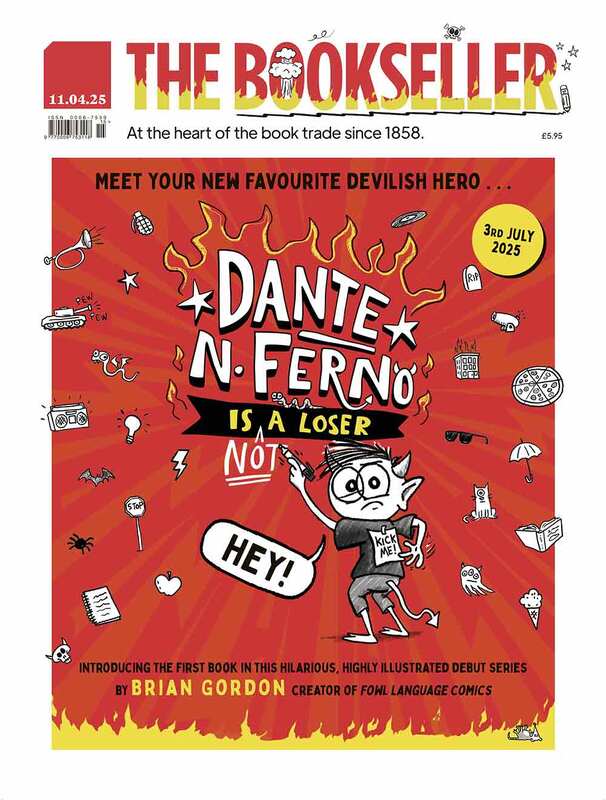

...moreMotherwell, the incisive memoir by Deborah Orr, unpicks the complexities of familial relationships.

Over the past year, I have had the privilege of being among the early readers of some outstanding memoirs which chart their authors’ challenging childhoods and the after-effects thereof: Educated by Tara Westover; Lowborn by Kerry Hudson; and My Past is a Foreign Country by Zeba Talkanhi to name just three.

In Motherwell: A Girlhood, Deborah Orr does something subtly different. While—like Lowborn—it is a memoir of a Scottish working-class upbringing, in her case in a series of council flats and houses in the Lanarkshire town of Motherwell, there is little obvious misery. Orr had two loving parents and did well at school. And while there were few luxuries and no fancy holidays, she wanted for very little. But still she couldn’t wait to get away. At 18, she left to go to university, and then moved to London, carving out a hugely successful career as one of our most incisive journalists and commentators. The first female editor of the Guardian’s Weekend magazine by the age of 30, Orr is also a playwright and the co-creator of “Enquirer”, commissioned by the National Theatre of Scotland, performed around the country and broadcast on BBC Radio 4, and shortlisted for New Play of the Year in the Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland.

In Motherwell: A Girlhood, Deborah Orr does something subtly different. While—like Lowborn—it is a memoir of a Scottish working-class upbringing, in her case in a series of council flats and houses in the Lanarkshire town of Motherwell, there is little obvious misery. Orr had two loving parents and did well at school. And while there were few luxuries and no fancy holidays, she wanted for very little. But still she couldn’t wait to get away. At 18, she left to go to university, and then moved to London, carving out a hugely successful career as one of our most incisive journalists and commentators. The first female editor of the Guardian’s Weekend magazine by the age of 30, Orr is also a playwright and the co-creator of “Enquirer”, commissioned by the National Theatre of Scotland, performed around the country and broadcast on BBC Radio 4, and shortlisted for New Play of the Year in the Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland.

So far, so working-class girl made good. But in Motherwell, rather than celebrate this journey, Orr grapples with what the decision to leave cost her; and how it demonstrates the yawning generation gap between her and her parents that could never be bridged. Memorably framed through a series of long-retained objects from her childhood which Orr discovers in a bureau she inherits from her parents—among them a lock of her baby hair, her parents’ wedding photograph, her school reports—the result is an utterly riveting, often blackly comic, and astonishingly honest début memoir, striking in its understanding of how the places and people we come from make us who we are.

While Motherwell, with its astonishingly apt title, takes in all her family relationships including those with her late father, brother and extended families in both Scotland and England, centre stage is Orr’s complex relationship with her late mother, Win. Born and brought up in rural Essex, Win moved north of the border in the 1960s after marrying Orr’s Scottish father, John. Of both her parents, denied the opportunity for much formal education, Orr writes: “they had no idea how intelligent they were”. But Win appeared to have few aspirations beyond becoming a “brilliant housewife” and natural homemaker that she clearly was. “She was amazing,” writes Orr. “She was accomplished, resourceful, vivacious, terrifyingly well-organised and copiously talented as an artist and craftswoman… When I was little, I worshipped her.”

Flying the nest

But ultimately, Win had very little control over the course that her life would take. “In some part of my mother, stuffed down and denied, there was unwelcome cognisance that her life had been limited by her sex and class.” As a result, she couldn’t contemplate the idea that her daughter might want to make different choices from her own; and, backed by her husband, repeatedly undermined Orr’s attempts to assert her own identity. “If she had no agency in the Big World, why should other women have it?” When Orr left Motherwell to go to university, her mother railed against the idea that her only daughter could ever want to leave her orbit. “She lived in her own world and she wanted me to live in it with her.” Orr’s refusal to do so casts a long shadow of guilt over her adult life, and it is only in her late fifties, after the death of both of her parents, that Orr begins to understand jus t how deeply it has affected her.

The award-winning fiction writer and memoir author Alice Jolly recently told me that she believes you can’t write a good memoir without spilling some blood. The ruthless honesty in Motherwell cuts deep, and none of its protagonists escape unscathed—not Orr’s mother, nor her father, nor (though rather more tangentially) her ex-partner, Will Self. But her scalpel is at its sharpest when she turns it on herself; on her foibles, and on her poor choices. For example, though still proudly working-class, she is also quick to slice through her own inverted snobbery. “The more humble my beginnings, the more I appeared to have achieved. I emphasised my lowly parents to feel prouder of myself,” she writes.

Legacy of love

Ultimately what Motherwell does so well is to unpack— with great understanding and no mean wit—that complex and tangled mixture of light and shade that characterises so many parent-child relationships; relationships that are essentially loving but which—as Philip Larkin famously recorded—also brand us with character traits and hang-ups that remain with us all our lives. As Orr memorably puts it: “Your Mum and Dad may fuck you up, but only because they didn’t know how fucked up they were themselves.”

Motherwell is not a book lacking in affection. On the contrary, it is Orr’s heartfelt tribute to her home town, and to all that went into the making of her, for better and for worse. But written in her late fifties, having mothered two now grown sons of her own, it is also her attempt to gain control of her own emotional history at last. Early on, she writes of how her mother once named all her childhood dolls for her. “Win”, she writes, was “in charge of all the words”. In Motherwell, it is finally Orr’s turn to take charge.

This is not quite the usual interview-format Author Profile because sadly, having been diagnosed with breast cancer earlier this year, Deborah Orr was not well enough for our original intended interview to take place. In lieu of this, below is the prologue to Motherwell, an outstanding memoir which, publishing as it does in January, sets the bar very high for the genre in 2020.

Book extract

That view. That stunning, dystopian panorama. A world unto itself, stretched out perfectly flat as far as the horizon, monochrome like the telly. Except for the occasional blast of pale-custard. Spikes of flame, so fast-moving that they seemed solid, roared implacably into the sky, day and night. Gas burnoff. A steelworks twice the size of Monaco.

At the time it was built, Ravenscraig was the largest, most technologically advanced strip mill in Europe: the black, thumping heart of our town and the lives of everyone in it. We Orrs lived pretty much on the edge of the complex. Everyone did. But you could only ever fully grasp the monolithic achievement of the place from one high point, as you came into town from the north.

You were never, ever quite prepared for the Craig’s dark satanic majesty, no matter how many times you’d seen it. We lived in thrall to it.

Beyond all else, that denatured, slightly hell-like hyper-mechanised landscape provoked awe. It seemed indestructible, irrevocable. But it survived, intact for only thirty-three years, from 1959 until 1992. High industrial Gothic, one of the wonders of the post-war settlement. All gone now. The place turned out to be an elaborate folly.

Motherwell is the town I was born and bred in, a coal and steel town on the lip of the Clyde Valley. By the time I was thirty years old it wasn’t a coal and steel town any more. Motherwell lost its identity in the industrial restructuring of the 1980s, along with wave after wave of redundant workers. Personal identities were shattered. But group identity was shattered too. The people of Motherwell were used to being part of something much, much bigger than themselves. When it went, so quickly, Motherwell became a town without a purpose. I couldn’t stand the place, even when it was still in its pomp. But I loved it too. Still do.

Motherwell is where my mum lived, because that’s where my dad came from. Even at the start of the 1960s, women did what their husbands w anted, in matters large and small. But Win was from rural Essex and found life in Lanarkshire challenging. She explained all this to me from when I was old enough to listen, or maybe even long before. Yet, despite all those confidences, over so many years, Motherwell is the place where I failed to get to know my mother very well at all. Until after she was dead. That was when I started to realise that there were respects in which she hadn’t mothered well at all.