You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

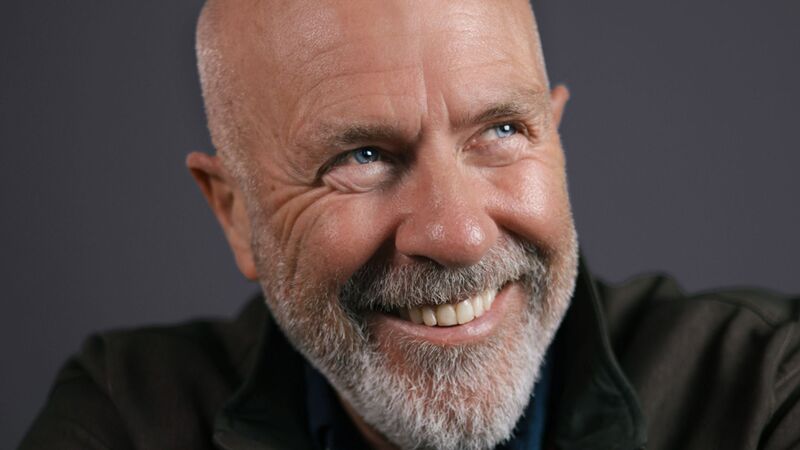

Deepa Anappara | 'His voice really came from my experience as a reporter'

Informed by her time as a journalist in Mumbai and Delhi, Deepa Anappara’s début is a fine portrait of modern-day India.

The roots of Deepa Anappara’s exceptional debut novel lie in her experience as a news reporter in India, a job she did for 11 years, specialising in education. She worked in cities such as Mumbai and Delhi, interviewing children who lived in the basti (slums) to find out whether the government’s education policies were reaching them. They spoke freely to her about their lives. "One of the things that kept coming up," she recalls, "was the disappearances of children, particularly in the north, where as many as 20 or 30 children had disappeared over a span of two or three years. Nothing had been done about it because these children were from poor families and didn’t have a voice or political power, and they could be easily ignored."

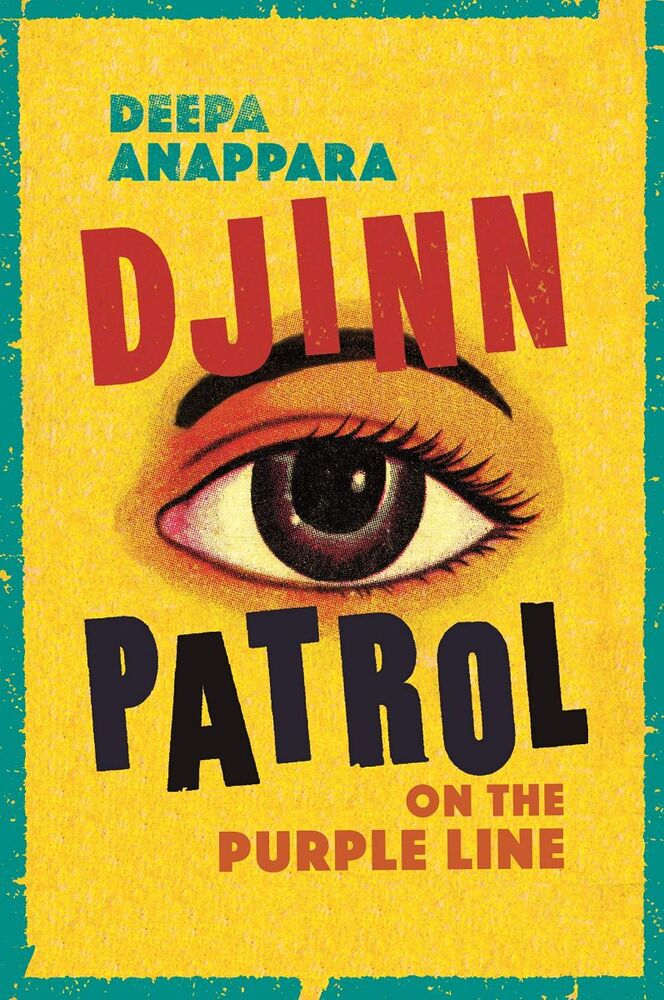

At the time Anappara, who grew up in Kerala before moving to Bengaluru (formerly Bangalore) to study journalism, was always on deadline with a news story to write. "[But] I used to wonder what it would be like to be a child living in that kind of neighbourhood; how do you deal with your friends disappearing? How do you deal with that kind of fear? And how do you explain it to yourself—as a child?" Her first novel, Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line, is a bravura attempt to answer those questions through fiction.

There are lots of Hindi words in the book because I felt that was one way to root it physically in its actual setting, but also try to convey the rhythm and cadence of the different language

The novel is narrated by nine-year-old Jai who lives with his Ma and Papa and older sister Runu-Didi in the basti on the outskirts of a unnamed sprawling Indian city. When one of his classmates at a large government school goes missing, Jai, an avid watcher of reality TV cop shows, decides to use crime-solving skills he has picked up from "Police Patrol" to find him.

The novel is narrated by nine-year-old Jai who lives with his Ma and Papa and older sister Runu-Didi in the basti on the outskirts of a unnamed sprawling Indian city. When one of his classmates at a large government school goes missing, Jai, an avid watcher of reality TV cop shows, decides to use crime-solving skills he has picked up from "Police Patrol" to find him.

He enlists the help of two friends, clever Pari who is always top of the class, and Faiz, who would do better at school if he didn’t also have to have a job to financially support his family. And so the fearless Djinn Patrol is formed. But then another child goes missing, and another

It is through Jai’s eyes that we see life in the basti, and his is an utterly convincing voice—lively, cheeky and irrepressible. And it is his voice that enables the novel to go to some very dark places indeed, without overwhelming the reader. It is notoriously hard to get child narrators right but Anappara’s creation is pitch-perfect. "His voice really came from my experience as a reporter," says Anappara, who now lives in Essex. "If I hadn’t had that experience and interviewed those people living in such neighbourhoods, I wouldn’t have been able to write it," she says. "Without romanticising poverty in any way—obviously it is a very difficult life—many of these children had learnt to survive in very difficult circumstances without losing their warmth or sense of humour."

Comforting stories

Over the course of the novel Anappara skilfully reveals the harsh reality that lies just beyond Jai’s understanding of his world: the stark inequality between the basti-dwellers and the residents of the "hi-fi" flats which overlook the slums, and where his own mother works as a maid. The problems of contemporary India are laid bare, the truly shocking police negligence—they are uninterested in the missing children as their parents cannot pay bribes—and the religious tensions between Hindus and Muslims, which are fanned by swirling rumours. Everyone believes in the supernatural, which Anappara says is an integral part of life in India. Threaded through the novel are mythical stories, told by a gang of street children, about ghosts and djinns who will protect them or take revenge on their behalf. "It’s very difficult for the characters in the book, their circumstances are incredibly hard and they’ve been ignored by those in power, who should have helped them," says Anappara. "They have nowhere else to turn, so they turn to these stories and tell each other these stories for comfort."

Anappara deliberately does not name the city in the novel, although she accepts that Delhi was an influence. "Setting it in a fictional city enabled me to explore the subject as I wanted to. I didn’t want it to be a true-crime novel in any way; I didn’t want it to be too close to the events that had actually taken place, even though the spark came from real-life disappearances. I didn’t want to narrate what had actually happened, and this was one way of just giving myself permission to write the story." Life in the basti, where neighbours live cheek by jowl and anybody’s business is everybody’s business, is vividly evoked, from the gossiping neighbours, to queueing for the outdoor toilets. The Bhoot Bazaar is a central focus for Jai’s investigations and a multi-sensory experience for the reader, from the scent of cardamom tea to the howls of the man having his ears scraped out and oiled by an ear-cleaner with a brass ear pick and some fluffy cotton wool. Anappara says she had to inhabit Jai’s life fully, and think about what he would notice: "Obviously he’s always hungry, he’s always thinking about what can he eat next and if anyone is going to give him free food."

One problem she encountered when writing the novel, which she began while studying for an MA in Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia (where she is now studying for a PhD), was that her characters think and speak in Hindi: "That was challenging, how do you capture a child’s voice in English when that’s not the language in which he is either thinking or speaking? There are lots of Hindi words in the book because I felt that was one way to root it physically in its actual setting, but also try to convey the rhythm and cadence of the different language."

Anappara’s promise was spotted early when a partial of Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line won the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Prize (previous winners include Gail Honeyman for Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine), as well as the Bridport/Peggy Chapman-Andrews Award for a First Novel and the Deborah Rogers Foundation Writer’s Award, within a single 12-month period. At the Frankfurt Book Fair last year, Chatto won the nine-publisher auction in a joint acquisition with Penguin Random House India.

The central mystery of the novel concerns the whereabouts of the disappeared children. Have they been spirited away by djinns, or have they met a more earthly fate? After each child disappears there is a break in Jai’s narration and we hear from the children themselves. In real life these children exist only as shadowy figures in the news reports, says Anappara. "I felt that by including their stories and having them speak for themselves, the reader gets a better sense of who these children were and the magnitude of the potential that’s been lost."

She wanted to show the real people behind the shocking statistic—up to 180 children are believed to go missing in India every day, but the real number may be even higher. "I really wanted to write this story, essentially, because these children had disappeared and there was not enough discussion about them. Their stories should have been part of the public discourse—and they weren’t."

Book extract

I look at our house with upside-down eyes and count five holes in our tin roof. There might be more, but I can’t see them because the black smog outside has wiped the stars off the sky. I picture a djinn crouching down on the roof, his eye turning like a key in a lock as he watches us through a hole, waiting for Ma and Papa and Runu-Didi to fall asleep so that he can draw out my soul. Djinns aren’t real, but if they were, they would only steal children because we have the most delicious souls.

My elbows wobble on the bed, so I lean my legs against the wall. Runu-Didi stops counting the seconds I have been topsy-turvy and says, ‘Arrey, Jai, I’m right here and still you’re cheating-cheating. You have no shame, kya?’ Her voice is high and jumpy because she’s too happy that I can’t stay upside-down for as long as she can.

Didi and I are having a headstand contest but it’s not a fair one. The yoga classes at our school are for students in Class Six and above, and Runu-Didi is in Class Seven, so she gets to learn from a real teacher. I’m in Class Four, so I have to rely on Baba Devanand on TV, who says that if we do headstands, children like me will:

• never have to wear glasses our whole lives

• never have white in our hair or black holes in our teeth

• never have puddles in our brains or slowness in our arms and legs.