You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

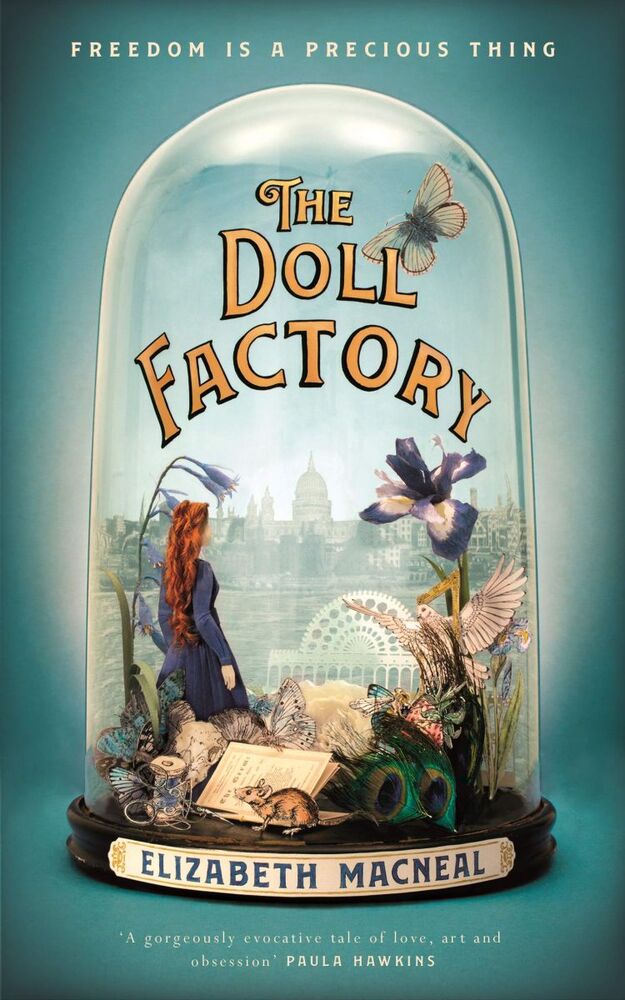

Elizabeth Macneal | 'I wanted to understand the women in their movement, more than the men'

Charlotte Eyre

Charlotte EyreCharlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

Elizabeth Macneal reveals both the macabre and painterly inspirations behind her sought-after debut The Doll Factory.

Charlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

Elizabeth Macneal’s teenage obsession with Pre-Raphaelite painters sowed the seed for her début novel, a gripping Victorian-age drama about a young woman called Iris who works for a pittance as a doll-maker, but yearns to be an artist in her own right. By a twist of fate Iris catches the attention of artist Louis Frost, who asks her to model for him, and she is given the opportunity to set her dreams in motion. But at the same time another man, Silas Reed, an unsettling collector and taxidermist, has become enamoured with Iris and has plans to make her his own.

As an "obsessed" teenager Macneal hung posters of Pre-Raphaelite paintings on her wall and became interested in Lizzie Siddal, who was spotted by Walter Deverell while working in a milliner’s shop and later modelled for John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She eventually became Rossetti’s wife. "Although it was quite a tragic story, ultimately I was fascinated by that early trajectory, by someone who wanted to paint and was then transported into this world where she became almost a supermodel of that time.

As an "obsessed" teenager Macneal hung posters of Pre-Raphaelite paintings on her wall and became interested in Lizzie Siddal, who was spotted by Walter Deverell while working in a milliner’s shop and later modelled for John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She eventually became Rossetti’s wife. "Although it was quite a tragic story, ultimately I was fascinated by that early trajectory, by someone who wanted to paint and was then transported into this world where she became almost a supermodel of that time.

"I wanted to understand the women in their movement, more than the men," Macneal adds. "Iris challenges the principles of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and her painting is influenced by them, but her work is also a departure from their work. I wanted her to carve out her own space separate from them."

Victoriana

She initially toyed with writing a fictional biography of Siddal but decided against it when she realised she wouldn’t be able to have as much fun with the plot as she would have liked. (She also didn’t feel like she would have done Siddal justice.) But when the idea of a collector came to her while studying Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia, the project started to come together.

"There is a museum in Hackney called The Viktor Wynd Museum of Curiosities, and that was where I got the idea for a collector in the weird and macabre, and when I started to write about a collector, I thought, ‘Hang on, the collector who I can’t make work in the present day is actually Victorian.’"

Silas, like the painters, is also creative and ambitious—the painters want to get their works into the Royal Academy; Silas wants his to be displayed at the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park—and was "so much fun" to write, says the author. Silas is obsessive and odd yet pitiable and human, too, and Macneal was keen not to present him as a "cardboard cut-out" villain. "If I had a character who was a collector, I wanted to make sure he was as complex as the collecting desire can be. I wasn’t interested in a cardboard cut-out. For a start you can make someone more threatening if the reader can see a shred of humanity in them. That’s more believable and more unsettling."

Society and class also play a big part in the narrative, so in addition to the elite world of the Royal Academy there is also the reality of life for the working classes, demonstrated by Albie, a young orphan with no teeth, whose sister at one point in the story pretends to be dying of consumption because punters will pay more money to have sex with her. The author wanted to show all levels of society, from the high echelons of the Royal Academy to the "grime and the filth" of "what would have been everyday life for so many people".

Victoriana

Macneal was born in Edinburgh and studied English at Oxford University, where she did a dissertation on clutter in 1850s literature, and describes herself as being obsessed with Victorian literature, both that which was written at the time (Dickens, Eliot, Thackeray) and books set during that period by modern writers such as Sarah Waters and Sarah Perry. Her expansive knowledge of the period shines through every chapter of the book, where she weaves real events and characters (Dickens’ damning of the Pre-Raphaelites work being one example) with the fictional story. Many early readers (including the author of this article) didn’t even realise the character of Louis Frost wasn’t a real painter. "Lots of people have asked that and looked him up, which is quite gratifying," she laughs. "Even my husband asked me which gallery Louis’ paintings were in!"

Macneal began writing The Doll Factory two years ago. In her twenties she wrote two children’s books, both of which were turned down by publishers. She then decided to take a job as a management consultant to save money for a creative writing course and started an MA at the University of East Anglia in 2017.

She began working on the novel towards the end of her course, where her tutors were Joe Dunthorne (who once rescued the novel from the bin), Giles Foden and Rebecca Stott. "Then I wrote it relatively quickly, about 5,000 words a day," she says. "It was almost like I had nothing to lose. I’d been rejected twice before and this was my chance."

Factory records

The novel went on to win the Caledonian Novel Award, where one of the judges was literary agent Madeleine Milburn, who took Macneal on as a client. "[Madeleine] kept saying, ‘This is going to be big’, and I kept trying to break it to her that she was wrong and that nobody would want it. I really believed that," says the author. "It went on submission one Friday and by midday on Tuesday we had 14 offers. It was crazy."

She chose Picador, saying: "I couldn’t get over how intelligent Sophie [Jonathan, the editor] was. The whole team was fantastic in the way they talked to each other and about each other. There was so much respect, and the hierarchy fell away." The book is due for release on 2nd May and Macneal, a successful potter as well as an author, is currently working on designing her own endpapers for The Doll Factory, and a second, standalone novel, also set in the 19th century. A TV deal for The Doll Factory has been struck, too.

She has no plans for now to return to The Doll Factory, despite the rather open ending. "In my head the story finishes there. I’m happy to leave it up to the reader to decide. All people can take from the book is what I write."

Extract

When the streets are at their darkest and quietest, a girl settles at a small desk in the cellar of a dollmaker’s shop. A bald china head sits in front of her and watches her with a vacant stare. She squeezes red and white watercolours on to an oyster shell, sucks the end of her brush, and adjusts the looking glass before her. The candle hisses. The girl narrows her eyes at the blank paper.

She adds water and mixes up fleshy colours. The first streak of paint on the page is as sharp as a slap. The paper is thick, cold-pressed, and it does not cockle.

In the candlelight, the shadows magnify, and the edges of her hair are one with the blackness. She paints on, a single sweep for her chin, white for her cheekbones where the flame catches. She copies her faults faithfully: her widely spaced eyes, the deformed twist of her collarbone. Her sister and mistress are sleeping upstairs, and even the shushing of her paintbrush seems an intrusion, a deafening rally that will wake them. She frowns. She has made her face too small. She meant to fill the page with it, but her head floats above

a blank expanse. The paper, on which she spent a week’s saved wages, is ruined. She should have sketched the outline first, been less hasty to begin.