You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

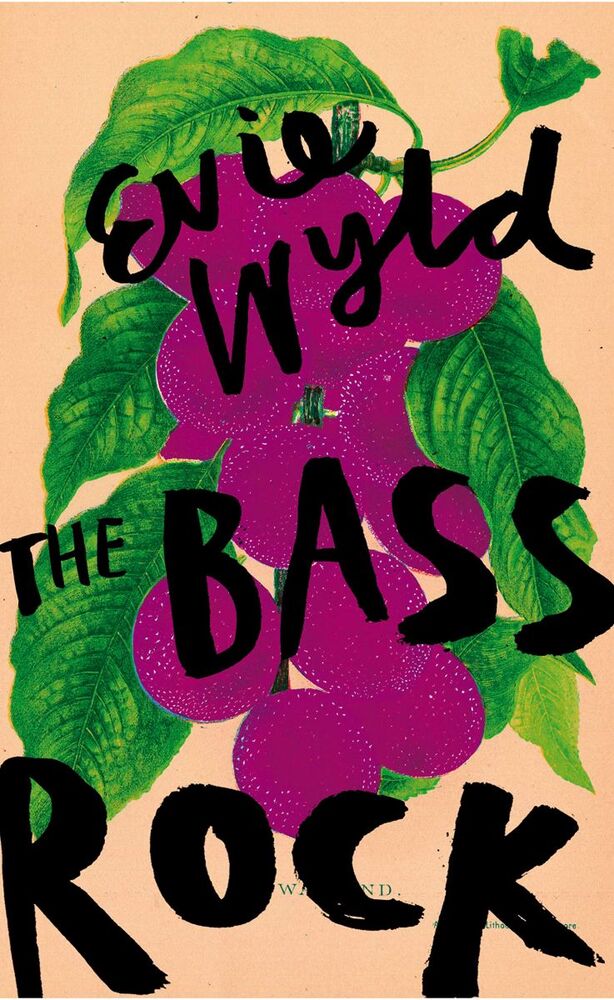

Evie Wyld | 'The Bass Rock is a book about paying attention to your inner voice, your instinct'

With two acclaimed novels under her belt, Evie Wyld’s dazzling new work looks set to win further praise.

For a writer with two published novels to date, Evie Wyld has accrued a veritable haul of prizes. Her 2009 début, After the Fire, A Still Small Voice, which explored the trickle-down effect of trauma on the lives of two Australian men, scooped the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, one of the oldest literary prizes in the UK and awarded to a writer under 35.

Her second novel All the Birds, Singing, the story of shearer Jake Whyte and her dark, abusive past, was set partly in Australia. It secured Wyld a place on Granta’s once-in-a-decade Best of Young British Novelists list in 2013. The novel was shortlisted for the Costa Best Novel Award and went on to win three prizes including Australia’s top literary prize, the Miles Franklin Award. Wyld was born and raised in south London, but her mother is from Australia. Growing up, Wyld spent alternate summers on her maternal grandparents’ sugar cane farm in New South Wales, and has spoken of Australia as “the first place I go when I am thinking creatively”.

“I think you can only write what you can write and if you try and crowbar in something zeitgeisty, by the time it publishes [the trend] will be gone anyway. That’s one of the reasons why I feel, although it is relevant, this is not a #MeToo book

The Bass Rock, her third novel, has no discernable link to Australia. It tells the stories of three women across four centuries whose lives are lived—in part—under the shadow of the Bass Rock, which looms out of the water off the coast of North Berwick in Scotland. But when we meet in a Peckham café, around the corner from the independent bookshop she co-owns, Wyld—friendly and down-to-earth—tells me that it may be the first novel she has written that is not set in Australia. Yet it was a deeply disturbing online map of that country that set her thinkin

The Bass Rock, her third novel, has no discernable link to Australia. It tells the stories of three women across four centuries whose lives are lived—in part—under the shadow of the Bass Rock, which looms out of the water off the coast of North Berwick in Scotland. But when we meet in a Peckham café, around the corner from the independent bookshop she co-owns, Wyld—friendly and down-to-earth—tells me that it may be the first novel she has written that is not set in Australia. Yet it was a deeply disturbing online map of that country that set her thinkin

Titled “The Australian Femicide and Child Death Map”, it was created by Australian journalist Sherelle Moody to illustrate the number of women and children who have died a violent death. “There are hundreds of hearts all over this map and if you click on one, it gives you a little run down of who it was that was found. A lot of the time it’s ‘unknown woman’ and [Moody] puts as much information as she can about it,” says Wyld. “There are so many unknown women. It just started me thinking about how you, as a woman, walk through these ‘death zones’ often. I don’t think I’ve met a woman who, when the subject has come up, hasn’t had a moment when they have feared for their lives.”

Unfolding stories

In the novel the three women’s stories unfold, each vividly told and compelling, and it becomes clear how each is restricted or controlled, in ways big and small, by the men in their lives. In the present day is Viv, nearly 40 and adrift with a complicated past. She is in North Berwick to sort out the empty house which belonged to her grandmother, Ruth. In the novel’s riveting opening chapter, which would work as a perfectly contained short story, she narrowly avoids disaster in a supermarket car park late at night, thanks to a local woman, Maggie, who at first seems to be the threat.

The novel then moves back to the 1950s, when upper-middle-class Ruth, grieving the death of her brother in the war, has recently moved up to Scotland to marry an emotionally distant widower and take on two step-children. Wyld explains that the events in Ruth’s life are based on her own paternal English grandmother, who also met a bereaved older man with two sons. “I think what I wanted to do was write an alternative version of her life because I knew her as a very tall, quite unhappy, alcoholic chain-smoker, very posh, incredibly bored and very smart, never having done anything with her brain,” says Wyld. “But [I am] always aware as a writer that there are other sides to people.”

The third strand is set even further back in time, in the 17th century, where a girl named Sarah is accused of witchcraft and flees the village. In contrast to Viv and Ruth, Sarah’s story is told by a young man, Joseph, who helps to save her from the men who would kill her. But his intentions are murky. And it becomes clear that he thinks of her as a possession rather than an equal.

To read The Bass Rock is to become aware of the violence and control levelled against women through the centuries, from hostility and aggression to sexual abuse, rape and murder. It is beautifully written and powered by blistering force and righteous anger. “I think it changed me quite a lot to write it,” she says. “It’s about noticing and when you start noticing, you can’t stop.”

The Bass Rock is, Wyld says, “a book about paying attention to your inner voice, your instinct”. Spanning four centuries, it’s also a book “about how nothing has changed, really. Witch-hunting and the killing of witches has just slightly changed its angle” she thinks, and later summarises: “[It] never stopped, it’s just now called domestic violence.” The novel also explores the weight of this history of oppression and control on women today. But there is hope, at least for Viv, through female friendship and solidarity.

Bookshop experience

In addition to writing novels, Wyld, until quite recently, also sold them. Twelve years ago Australian Roz Simpson opened an independent bookshop in Peckham called Review, and offered Wyld a job as a bookseller when she wandered in as a customer. She worked there for 10 years. “I wrote my first book behind the till,” she says fondly. Now a co-owner, her shop duties are less onerous—she sends authors to Review for events and recommends books to stock—while Katia Wengraf now runs it day-to-day and does a much better job according to Wyld.

“I was much more ‘Black Books’ [the seminal 1990s sitcom starring Dylan Moran as the grumpy, misanthrophic bookshop owner Bernard Black], whereas [Katia] introduces customers to each other, and conducts relationships between them,” Wyld says of Wengraf.

Working in a bookshop and making decisions about which books to stock would give anyone a knowledge of the market and what is selling. Did that knowledge have any effect on her writing? “I don’t think it can, and not in a moral way, because if I could write a bestseller then I would write that,” she says, laughing.

“I think you can only write what you can write and if you try and crowbar in something zeitgeisty, by the time it publishes [the trend] will be gone anyway. That’s one of the reasons why I feel, although it is relevant, this is not a #MeToo book. It’s a book I could have easily written 10 years ago.”

Photography: Urszula Soltys