You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Frances Hardinge | 'My books are strange in quite different ways from each other'

Frances Hardinge’s eccentric backlist takes another unusual turn with a tale of the legacy of warring sea gods.

In her Twitter biography, Frances Hardinge describes herself as a "writer of downright odd children’s books", which seems a fair assessment when you consider some of her plots: a girl possessed by the ghost of a bear, a tree that bears fruit if you lie to it. "My books are strange in quite different ways from each other, which can’t make life easy for sales and marketing," she laughs when we meet at Macmillan’s King’s Cross office. But it is this very eccentricity that makes Hardinge’s work so distinctive and irresistible.

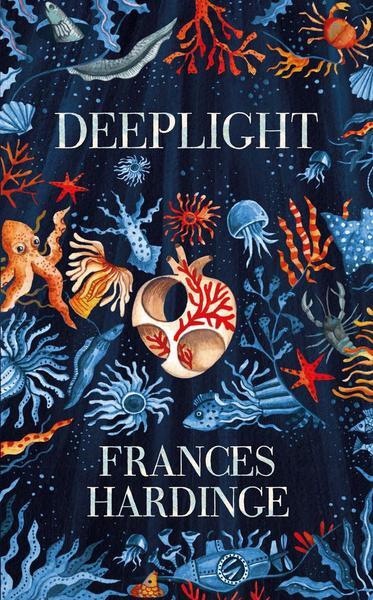

Her latest book, Deeplight, is no exception. It is set in the fantasy world of The Myriad, an archipelago of thousands of islands, once ruled by underwater gods as real and merciless as the coastlines and currents. The gods are now dead, but their relics are very much in demand and an entire industry has sprung up to salvage the "godware". Taking inspiration from 17th and 18th-century technology—"I didn’t want the submarines based on anything sensible"—she sends her characters beneath the waves in "relatively shonky diving equipment". On the island of Lady’s Crave, street urchins Hark and Jet have grown up in an orphanage, both products, Hardinge tells me, of their rough and ready environment. Now they are survivors on the edge of the underworld, scavengers diving for relics. When one extraordinary discovery of "a fragment of god that is perhaps not quite as inert as the others" changes their lives forever, it is the boys’ intense friendship that forms the emotional and moral core of the book.

Her latest book, Deeplight, is no exception. It is set in the fantasy world of The Myriad, an archipelago of thousands of islands, once ruled by underwater gods as real and merciless as the coastlines and currents. The gods are now dead, but their relics are very much in demand and an entire industry has sprung up to salvage the "godware". Taking inspiration from 17th and 18th-century technology—"I didn’t want the submarines based on anything sensible"—she sends her characters beneath the waves in "relatively shonky diving equipment". On the island of Lady’s Crave, street urchins Hark and Jet have grown up in an orphanage, both products, Hardinge tells me, of their rough and ready environment. Now they are survivors on the edge of the underworld, scavengers diving for relics. When one extraordinary discovery of "a fragment of god that is perhaps not quite as inert as the others" changes their lives forever, it is the boys’ intense friendship that forms the emotional and moral core of the book.

Lovecraft’s lore

The gods came first in Hardinge’s imagining of this world. Eschewing the often vague and off-the-page deities of fiction, Hardinge yearned for something more tangible. "What if you have some that just blatantly, palpably exist and interfere with shipping and have been a reality of life for a significant number of people for a very long time?" Her inventions are strange and terrible: The Glass Cardinal, who throttled galleons with translucent tendrils; The Red Forlorn, floating like a cloud of blood in the water; and The Hidden Lady with snaking hair and spider-crab legs. They are, she says, "a little bit Lovecraft inspired, but also with elements of some of the more bizarre and wonderful creatures of the deep". She began to wonder what would happen if all the gods suddenly died. "You then have an entire population who had been living in dread of them for centuries, who then have to adapt. I had this image of dead gods being brought into harbour, and entire industries building up on these islands, dealing with the logistics of stripping, selling, boiling down and exploring all the fragments of these dead monstrosities."

Storytelling is important in Deeplight, particularly in the character of Hark who, she explains, "represents a lot of what is good and bad about stories". At first he tells stories in order to survive. "He is a con artist and, of course, stories can be used to obfuscate and to replace the truth." He has built barriers to protect himself, but storytelling leads him to compassion and understanding: "Stories are also engines for empathy." Stories act as a kind of communal memory, too; later in the book Hark becomes a confidante to the priests who once communed with the gods. He is a storykeeper, "somebody who is effectively a library of lives, a purveyor of immortality".

Storytelling, truth and lies are themes common to much of Hardinge’s work, feeding into questions about religion and morality. "I am fascinated by people. I am fascinated by what they believe and what they don’t [believe] and why, and what they want to believe." One of her characters muses that "fear is the dark womb where monsters are born and thrive", predicting a new era of horror fuelled by "a poisonous nostalgia". Is this a nod to current events? "Unfortunately I think it’s relevant to most times," she says. Calling herself "a cynical optimist for our species", she continues: "We are not at our best when we are frightened. Fear is like hate, in that it thrives on ignorance and unfamiliarity."

For the first time, Hardinge has a deaf lead character, Selphin, who lost her hearing during an underwater run-in with other scavengers. Deeplight’s universe, with its deeply inadequate diving equipment, is rife with characters with hearing loss, who are known as the "sea-kissed". This was sparked by a suggestion from a 13-year-old deaf reader, who has been an "absolutely invaluable" sensitivity reader. Hardinge is also working with the National Deaf Children’s Society and its Young People’s Advisory Board.

It’s clear she has had enormous fun researching Deeplight, reading about very old designs of submersibles, the first trip of the Bathysphere, and deep sea creatures "which are tremendously fun and actually rather beautiful, in nightmarish ways". Although she asserts that her writing process is "still more chaotic than it should be", she creates extensive brainstorming documents, and sometimes timelines and spreadsheets, finding it helpful "to have that road map [when I am] two-thirds of the way through the book—when I start to hate it". Her productivity "massively benefits from deadlines", when she tends to revert to her naturally nocturnal state. "At the risk of sounding a little vampiric, I do wake up a bit after dark."

Finding her feet

Hardinge recalls "scribbling stories from quite a young age", including a time-travelling, murder-mystery chiller which, she admits, would subsequently prove to be rather on-brand. The rich seam of 1970s British children’s fiction provided much inspiration: Alan Garner and Susan Cooper, whose Dark is Rising series had "a critical role in shaping my imagination". Other favourites were Nicholas Fisk ("one of my early introductions to science-fiction") and Leon Garfield, who got her hooked on historical fiction. She wrote for many years before her friend, writer Rhiannon Lassiter, suggested that her work in progress was actually a children’s book. "Everything suddenly made a lot more sense." Her début, Fly By Night, was published in 2006 and won the Branford Boase Award.

The deal for her next three books was, she says, "generous to the point where I could write full-time", and Macmillan, she is keen to stress, "has continued to show faith in my strange books". Early in 2016, Hardinge joined Philip Pullman as one of only two children’s authors to have won the overall Costa Book of the Year, resulting in her biggest commercial success to date. "I was really glad that happened with my seventh book, and not my first." Did she feel under pressure to write a certain type of book, or even a sequel, after the success of The Lie Tree?

"I can’t write for a market or a demographic. My imagination thrives off experiments. I feel my books should scare me a bit, that I should be out of my comfort zone."