You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

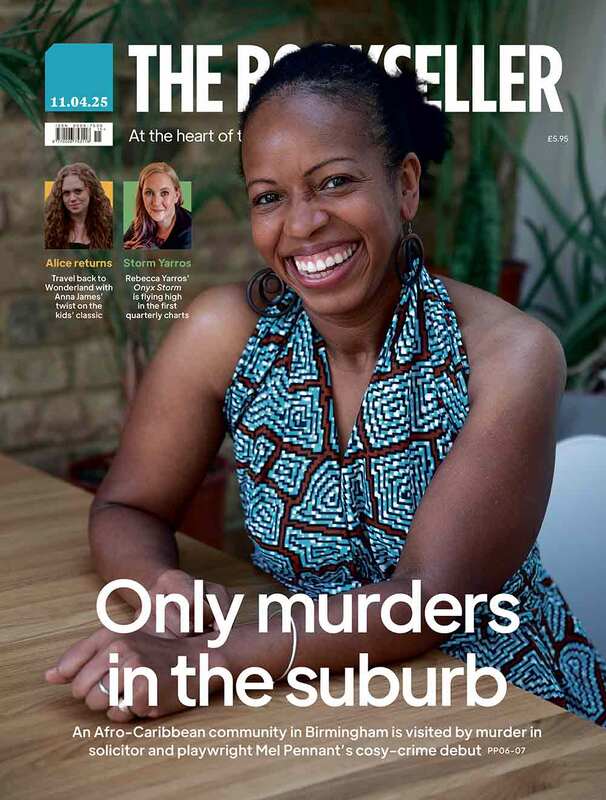

Jeffrey Boakye | 'I feel like the debate is opening, but it’s not always a safe debate'

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson worked as a Waterstones bookseller, and as a book publicist before becoming a freelance writer in 1997. The Bookseller’s

...moreSchoolteacher and writer Jeffrey Boakye’s second book is a charismatic and entertaining attempt "to explore the central nervous system of racial semiotics".

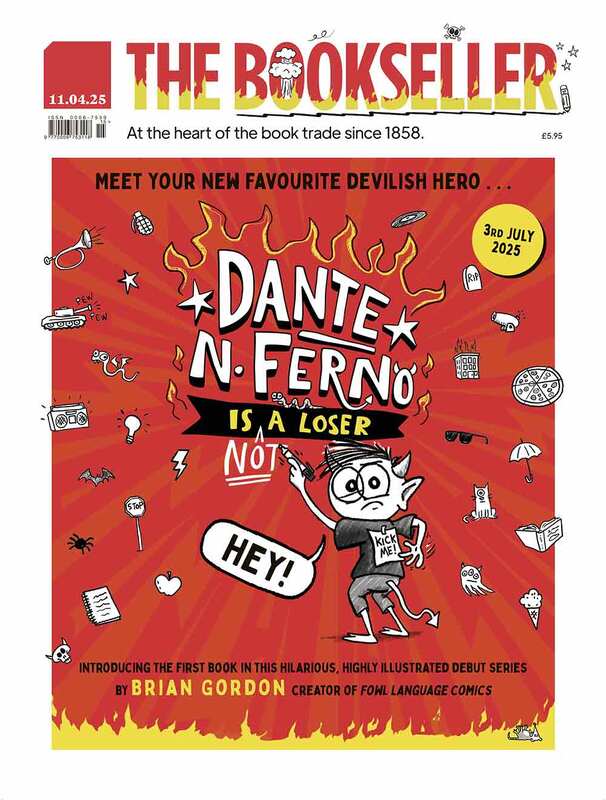

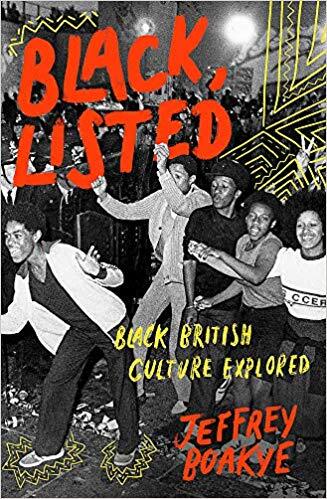

At the beginning of his charismatic and consistently entertaining new book, Black, Listed: Black British Culture Explored (Dialogue Books), Jeffrey Boakye takes us back to an identity-jangling incident that happened when he was six. "I’ve been black since about 1988, when I was colouring in pictures of priests at Corpus Christi Roman Catholic Primary School in Brixton Hill," he declares, going on to describe how the girl colouring alongside him started asking around for a skin coloured pencil. Being an "ever-helpful people pleaser", he handed her a brown one, only to be told: "that’s not skin colour". "Hello inadequacy. Have you met otherness? Pleased to make your acquaintance," he writes, recalling his feelings at that moment.

This anecdote sets the tone for the book’s exploration of a whole lexicon of words and phrases that "melanin-heavy human beings might find themselves being referred to as". From Angry Black Woman to Yardie; from Othello’s moor to J K Rowling’s mudblood "half-castes"; from terms of endearment to the most contentious racial slurs, all of them have in some way come to define 21st-century black identity. In cataloguing such language, Boakye’s mission is to expose "the central nervous system of racial semiotics, to shed new light and offer new perspectives".

This anecdote sets the tone for the book’s exploration of a whole lexicon of words and phrases that "melanin-heavy human beings might find themselves being referred to as". From Angry Black Woman to Yardie; from Othello’s moor to J K Rowling’s mudblood "half-castes"; from terms of endearment to the most contentious racial slurs, all of them have in some way come to define 21st-century black identity. In cataloguing such language, Boakye’s mission is to expose "the central nervous system of racial semiotics, to shed new light and offer new perspectives".

Let’s raise lots of questions but let’s not do it in a defensive way or in a forlorn way. Even though it contains some of the heaviest stuff you could talk about... some of the black experience is just funny

Boakye and I meet to talk about the radical tapestry that is Black, Listed over tea in the incongruously sterile setting of a Doncaster shopping centre. A London native who has hitherto spent his entire teaching career in secondary schools in the capital, he recently moved to South Yorkshire with his young family, tasked with setting up the first UK school based on an American model which has proved extremely successful in boosting the life chances of marginalised young people who have fallen through the cracks of mainstream educational provision.

Grabbing an hour away from his packed schedule, Boakye tells me that Black, Listed, his second book, was directly inspired by the format of his first, Hold Tight: Black Masculinity, Millennials and the Meaning of Grime (Influx Press, 2017), in which he reflects on life as a black man in Britain today through 50 seminal tracks that "make up Grime’s DNA". "I wanted to do another book that explored identity, race and popular culture through a list of things, and I thought it would be interesting to look at words to do with race that have intersected with my life.

So I wrote down all the descriptive terms I felt were relevant to the black experience. It was amazing—I hadn’t realised there were so many! I didn’t have to think, ‘How am I going to talk about sovereignty? How am I going to talk about African-ness? How am I going to talk about black hair?’ There was already a word to take me there." Soon, Boakye also had a vision in his head of a periodic table which would "lay out all these words in a scientific way, putting them in different categories". It took a while to craft but the resulting periodic table appears at the beginning of the book, and gives a ingenious pictorial representation of the sustained narrative about identity which Boakye weaves though his compendium of descriptors.

Raising questions

Despite, or perhaps because of the inventiveness of his proposal, not all the publishers who read it grasped what Boakye was trying to do. "They knew it was interesting, but I don’t think many of them knew how to edit it or present it". Eventually the book found a home with Sharmaine Lovegrove at Dialogue Books. Coincidentally, at the age of 16, Lovegrove had been at the sister school to the one Boakye attended in Wimbledon, but the two had never met. But as his new publisher, her agenda "just seemed to dovetail with my own. Which was: let’s talk about the black British experience. Let’s raise lots of questions but let’s not do it in a defensive way or in a forlorn way. Even though it contains some of the heaviest stuff you could talk about... some of the black experience is just funny," says Boakye.

And indeed, while deadly serious in intent, Black, Listed is also frequently hilarious. For example, while highlighting his experience as a teen in the 1990s and demolishing the term "black British" in the process ("blackness and Britishness are not mutually exclusive"), he writes "No word of a lie: a black guy on Blind Date could clog up the house phone for the rest of the evening." There’s a very funny reflection on the word "brown", based on Boakye’s experience of listening, somewhat incredulously, to white people talking about tanning ("I am less likely to

be called brown than the average white person despite having properly brown skin"). Repeatedly taking racism and political correctness by the scruff of the neck, his writing is vivid, challenging and wonderfully subversive.

Boakye’s educational experience is instrumental to the inclusive tone he strikes in Black, Listed. "I feel like the debate is opening, and we’re becoming more aware of marginalised experiences, but it’s not always a safe debate. As a teacher I often have to find ways to make unsafe conversations safe. Young people need to be able to honestly express their fears and their thoughts and their reactions. And as a teacher you can’t just leave that to random chat in the playground—you actually have to create spaces where you can talk about these things, letting the debate happen in a non-judgemental way. I think that Black, Listed is an attempt to do that with people who aren’t sitting in front of me. By opening up my own vulnerabilities and talking about personal things, I’m trying to humanise the black experience".

If my own reading is anything to go by, Black, Listed is a book that talks very directly to white people about race, leaving them in no doubt about what it’s like to be constantly defined, not only by the colour of your skin, and the birthplace of your parents and grandparents, but by terms that often make no sense whatsoever. But it is also just as uncompromising and discomfiting as Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race (Bloomsbury), a book Boakye greatly admires. The fact that so many of the terms he describes still have common currency exposes the structural faults in our society that, says Boakye, are "crippling our ability to go forward. Everyone is a victim of dominant whiteness. I really believe it messes everything up."

Boakye hopes his "overcoming the monster narrative" ("the monster not being white people or white society, but the actual concept of whiteness itself") will be read by a broad liberal audience, in particular by Generation Z. He also wants it to speak "to the black diaspora in the UK", while acknowledging that it is rooted very much in his own particular experience: "If you

gave someone else the same list of words, they’d come to different conclusions." In this he is also mindful of his two young sons, who, he says, "are going to have experiences that I can’t appreciate. They’re mixed race, dual heritage, and that’s a complication I’ve never had to think about. But they will still be seen as black in a very white part of the world, and they are going to have to navigate that."

This look to the future is significant perhaps. While Boakye would be the first to say that a post-racial society is "not happening anytime soon", his desire for a young readership for Black, Listed seems invested with his hopes that “one day, people will look back and think, did we really once refer to people by such deeply opposed terms as ‘black’ and ‘white’?"

Extract

Blackness as a racial concept is inherently oppositional. It’s a binary truth that only works insofar as being the opposite of white, which means that I have spent the vast majority of my consciousness in a state of conceptual conflict. As a label it does the important job of confirming something that is already very obvious: that a person who isn’t white, isn’t white. But labels don’t just identity what something is, they create meaning. Black is easily the most ubiquitous of all the elements listed in the book, so much so that the assumption is that it is a neutral concept in the racial mix. A given.

The terrifying reality is that it is quite possibly the most volatile of all the elements, in that it creates the sharpest contrast to a dominant other whilst appearing innocuous.