You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Jung Chang | 'I think China is probably at a critical moment'

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

The modern fairytale of the Soong sisters is well known across China. Bestselling author Jung Chang looks set to bring the sisters’ stories to a global audience.

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

When Jung Chang was growing up in Mao Zedong’s China, the best-known modern fairytale told was of the three Soong sisters from Shanghai. The story went that "one loved money, one loved power, and one loved her country".

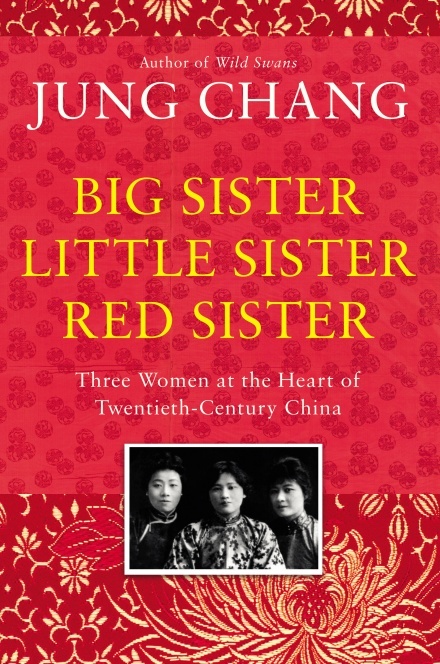

"Every Chinese person in communities the world over knows about the sisters," Chang tells me on the phone from New York, where she is on a visit from her home in London. Now the sisters are set to become familiar to non-Chinese readers too, with the publication of Chang’s utterly engrossing new book Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of 20th-Century China. Like her 1991 début Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China—one of my favourite ever memoirs—it also stars a trio of extraordinary women, each of whom enjoyed tremendous privilege and fame, but also endured constant attacks and mortal danger as well as heartbreak and despair. Their gripping collective story reads like Wild Swans meets the Mitfords; and the history feels remarkably close to our own times too, especially given that the youngest sister, May-ling (Little Sister) died as recently as 2003, aged 105.

"Every Chinese person in communities the world over knows about the sisters," Chang tells me on the phone from New York, where she is on a visit from her home in London. Now the sisters are set to become familiar to non-Chinese readers too, with the publication of Chang’s utterly engrossing new book Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of 20th-Century China. Like her 1991 début Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China—one of my favourite ever memoirs—it also stars a trio of extraordinary women, each of whom enjoyed tremendous privilege and fame, but also endured constant attacks and mortal danger as well as heartbreak and despair. Their gripping collective story reads like Wild Swans meets the Mitfords; and the history feels remarkably close to our own times too, especially given that the youngest sister, May-ling (Little Sister) died as recently as 2003, aged 105.

In 1927, May-ling married Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, thus becoming first lady of pre-Communist China, and a political figure in her own right; while her eldest sister, Ei-ling (Big Sister)—along with her politician husband H H Kung—was chief adviser to Chiang. Ching-ling (Red Sister) married Sun Yat-sen, the founding father of the Chinese republic and later became Mao’s vice-chair and thus a sworn political enemy of her sisters.

I ask Chang how she remembers the fairytale told to her as a child. "Red Sister—Mao’s vice-chair and the ‘one who loved her country’—was presented as the mother of new China and was said to be very beautiful. But I also recall the widespread rumour about her that she was living with, or some said married to, her bodyguard, who was less than half her age. I was amazed because only Red Sister was talked about in this way. Otherwise, nobody was allowed to talk about the leaders’ private lives.

"I also remember very well the story about Little Sister, May-ling. It was said she had wonderful skin because she bathed every day in milk. To us children that was absolutely outrageous, because milk was precious and nutritious but unobtainable for anyone except the elite. Chiang Kai-shek was the ruler of China who was deposed by Mao, and so our number one enemy. And so it was put into our heads that his wife was this outrageously self-indulgent woman who led an unbelievably decadent and luxurious life. Ei-ling was less talked about. But the image of her was as the ‘one who loved power’ and that she was corrupt and somehow sinister."

Learning the craft

Chang was first offered the chance to uncover the truth behind the fairytale in the 1980s, when she received a commission to write about Ching-ling. She abandoned the project however, feeling "curiously uninvolved" with it. "I wasn’t a writer yet," she tells me. Fast-forward over 30 years, and Chang, by now the author of two further books, Mao: The Unknown Story, co-written with her husband, Jon Halliday, and Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China—as well as Wild Swans—was far better placed to revisit the stories of her childhood, her extensive research having left her intimately acquainted with the huge sweep of Chinese history. It was only when she began to gain an understanding of the personal lives of the Soong sisters that she felt compelled to write about them, however. "I discovered the drama in their characters, their emotional conflicts and upheavals. Often people who are poles apart politically are also antagonistic towards each other personally. But these three sisters remained close and were genuinely fond of each other. I found that extraordinary."

As well as conducting interviews with those who had known the sisters, including the deputy bodyguard to Ching-ling’s rumoured lover, Chang undertook extensive archival research for Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister, notably in the US, where the three sisters were sent to school at a remarkably young age (May-ling was only nine) by their father, who also spent his formative years in the US. "He was baptised and virtually adopted by Methodists in South Carolina when he was a teenager, and his enduring faith in America was extraordinary," Chang tells me. She believes that the Christian faith that the sisters inherited from their father came—in the case of Ei-ling and May-ling—later to be an important tempering influence on the dictatorship of Chiang Kai-shek.

In fact, Chang portrays all three Soong sisters as women who played a crucial role in the history of China in their own right, and not merely on account of the significant marriages they made. But above all, she shows that they were canny and courageous survivors who outlived the powerful men in their lives. Ei-ling died in 1973 aged 85, Ching-Ling in 1981 aged 88.

The Soong sisters

And as readers of Wild Swans—a book that has now sold more than 15 million copies in 40 languages, but is still banned in China—will know, Jung Chang is also a survivor, in her case of the horrors of Mao’s China and of the Cultural Revolution. Having grown up within the privileged circles of the Communist elite, she saw her parents denounced and sent to distant labour camps. Her father was later driven insane and hounded to death, while Chang, still a teenager, was exiled to the edge of the Himalayas, where she lived and worked as a peasant and barefoot doctor, and then as a steelworker and an electrician, before becoming an English-language student at Sichuan University.

Knowing that Chang’s mother survived and was still alive at the time when Wild Swans was published, I ask after her. "She is still alive!" Chang tells me happily. "She is only 88! She lives in Chengdu. She is of course frail, but she’s not in pain. She too is a survivor." Permitted only a single trip of 15 days back to China each year, Chang tells me she feels blessed that her youngest brother and her sister live close to their mother and are able to care for her. "Because I cannot go back freely."

A second home

Chang came to the UK in 1978 to study at the University of York, where she took a PhD in Linguistics and became the first person from Communist China to receive a doctorate from a British university. How does she feel about this country, which has now been her home for much longer than China? "I have a deep-rooted love for Britain. Like other people I’m anxious about Brexit. But somehow my faith in this country is so strong I feel that somehow it’s going to—as they say—muddle through."

Is she similarly optimistic for the country of her birth? "I think China is probably at a critical moment. I’m holding my breath for its development, and I so wish and hope that it will emerge from this period to be more open and less repressive. And, yes, I have some faith and hope, because the door that has been opened cannot be closed again. Whatever censorship there is, I just don’t believe China can be dragged back to the awful Maoist days like when I was there."