You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Lara Maiklem | 'We’ll be the plastic age: the throwaway society'

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson worked as a Waterstones bookseller, and as a book publicist before becoming a freelance writer in 1997. The B ...more

The Thames riverbed proves to be inspirational for former publishing professional Lara Maiklem in a book that’s part memoir, part ode to a love of mudlarking.

Caroline Sanderson worked as a Waterstones bookseller, and as a book publicist before becoming a freelance writer in 1997. The B ...more

A Roman roof tile. Pieces of medieval ceramic in a gorgeous mottled green, including the rim of a cooking pot. Three types of Roman pottery, another shard that may well be Saxon, and one that looks very like 17th-century Delftware. A marble. Early handmade pins and nails. Metal aglets from a long-departed doublet and hose. Clay pipe heads from the Georgian era.

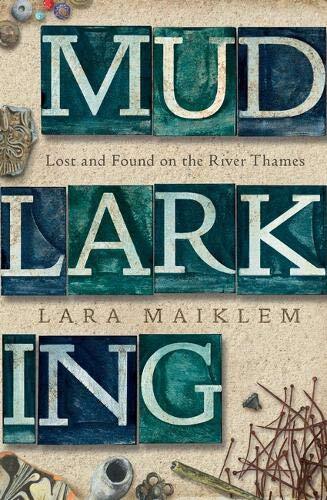

All these things I hold in my hands during my two hours down by the Thames at low tide with mudlark extraordinaire Lara Maiklem. Her first book, Mudlarking: Lost and Found on the River Thames, draws on her 15 years of fossicking on the foreshore by day and by night, and at all seasons; from central London right out to the estuary. Beautifully threading memoir through the history of London from prehistoric times to the present day, she documents many of her finds and uses them to bring the long-buried lives of ordinary people back to the surface. "It is often the tiniest of objects that tell the greatest stories," she writes.

All these things I hold in my hands during my two hours down by the Thames at low tide with mudlark extraordinaire Lara Maiklem. Her first book, Mudlarking: Lost and Found on the River Thames, draws on her 15 years of fossicking on the foreshore by day and by night, and at all seasons; from central London right out to the estuary. Beautifully threading memoir through the history of London from prehistoric times to the present day, she documents many of her finds and uses them to bring the long-buried lives of ordinary people back to the surface. "It is often the tiniest of objects that tell the greatest stories," she writes.

Earlier that afternoon, as we sit and talk in a riverside pub while we wait for low tide, Maiklem explains that it is exactly its tidal nature which makes the Thames "the longest and most varied archaeological site in the world". "Lots of people who live here take the river for granted even though it cuts our city in half. And they don’t think about the fact that twice a day, the water churns everything up and then goes down far enough for us to explore the riverbed. I can’t think of any other city with such a condensed history where that happens. For centuries, the foreshore was a working environment and much of what we find are the things people have dumped." I will later be astonished by the litter of clay pipe stems, testament to our formerly ubiquitous tobacco smoking habit; and by the dozens of animal bones scattered around, some still with the marks of butchery upon them.

Now in her forties, Maiklem—a self-described "natural daydreamer", grew up on a farm in Surrey with a river running through it. "My brothers were a lot older than me, so I spent a lot of time on my own. Mum would kick me out in the morning and I’d come back when I got hungry. So I grew up semi-feral, wandering around the farm and playing in the river with my dog, and doing all sorts of things I would never let my children do now." She credits her mother with giving her a great curiosity about the world around her. "We’d go on nature walks and she’d always encourage me to look carefully and notice the small things."

Back to nature

But as a teenager, Maiklem tired of life in the country. She moved to London as soon as she could, and "went wild" for a few years. "But then I rediscovered the calming nature of taking time out to look closely." She started going down to the water near her former home in Greenwich. "I was having a bit of crappy time and the river became my go-to place to get my head together." Soon she began picking objects up from the foreshore, fascinated by their history. Before long, mudlarking had become her private passion, pursued up and down the central London foreshore and beyond. As Mudlarking explains, the range of objects which wash up varies from place to place. In one of many enthralling stories in the book, Maiklem writes about the pieces of Doves Type she has found close to Blackfriars, remnants of the many thousands jettisoned into the river in 1913 by the typeface’s inventor, Thomas Cobden-Sanderson. Marvellously, the jacket’s design makes use of some of these salvaged pieces of type.

More recently, mudlarking has provided Maiklem with precious "me time" away from the demands of family life—she and her wife have seven-year-old twins. At home with two newborns, Maiklem—as "London Mudlark"—began posting some of her finds online, attracting a considerable following. As a result, agent Sarah Ballard contacted her to ask if she’d ever thought of writing a book. "I so nearly deleted the email," Maiklem tells me. Aside from a short spell as a Waterstones bookseller, Maiklem had worked in publishing editorial since leaving university, first in-house for DK and then for various illustrated publishers as a freelance. "So I knew the processes, but was quite happy never to write a book of my own." Ballard was persuasive, however, and Maiklem wrote a proposal which provoked great excitement on submission. Five publishers eventually took part in "a passionate four-round auction", and Maiklem chose to go with Bloomsbury, which was "willing to work on the book creatively with me, and has been exactly what I’d hoped."

Hunter gatherer

As well as regaling us with glorious stories from history, Maiklem also testifies to the objects from our own present that will greet future mudlarkers. "We’ll be the plastic age: the throwaway society. You don’t see much plastic here in central London: there are rubbish collectors and people say—‘Oh, the river’s so clean’. But go out to the Estuary and it’s just banks and banks of plastic—it’s horrible." Maiklem is also at pains in her book to advocate only responsible mudlarking, which requires the purchase of an official permit from the Port of London Authority (she sought special permission for me to accompany her). She is firmly among the "gatherer" type of mudlarkers, who only forage objects from the surface, without the aid of metal-detectors and the scraping and digging employed by the "hunter" types. "I don’t agree with digging. I don’t think it’s necessary—all you need are patience and time".

I predict that Maiklem’s book will prove deservedly popular. But given her love of solitary gathering, is she prepared for the wave of interest in mudlarking that it could generate? "Some mudlarkers will probably criticise me for encouraging more people to do it, because they think of it as ‘their stuff’. That’s like not sharing your toys. Everyone has a right to our shared history. And if these objects aren’t picked up they’re just going to wash or erode away. But I hope that my book will explain to people why it’s important not to take shedloads of stuff home, put it in a drawer and forget about it."

Before we go down to the foreshore, I marvel at one of the objects Maiklem has brought along to show me. It’s the broken-off end of a wig-curler: 18th century, maybe earlier. My thoughts turn to those periwigged portraits of Samuel Pepys who watched the Great Fire of London from a boat, close to where we now sit. That’s the happenstance fascination of mudlarking and the way it fires your imagination. "And it’s the fact that you can pick something up and know that you’re the first person in hundreds, sometimes thousands of years, to touch it. That’s an incredible feeling," adds Maiklem.

Book extract

It is the tides that make mudlarking in London so unique. For just a few hours each day, the river gives us access to its contents, which shift and change as the water ebbs and flows, to reveal the story of a city, its people and their relationship with a natural force.

If the Seine in Paris were tidal it would no doubt provide a similar bounty and satisfy an army of Parisian mudlarks; when the non-tidal Amstel River in Amsterdam was recently drained to make way for a new train line, archaeologists recorded almost 700,000 objects of just the sort we find in the Thames: buttons that burst off waistcoats long ago, the rings that slipped from fingers, buckles that are all that’s left of a shoe—the personal possessions of ordinary people, each small piece a key to another world and a direct link to long-forgotten lives.

As I have discovered, it is often the tiniest of objects that tell the greatest stories.