You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Louise Doughty | 'I thought of Apple Tree Yard as a serious and feminist indictment of the criminal justice system'

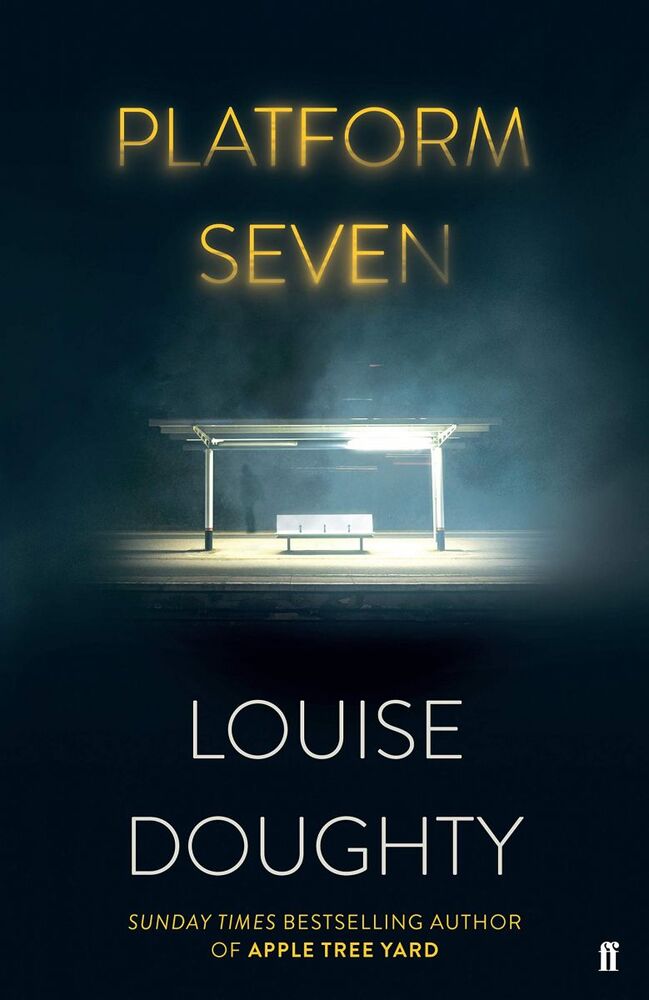

The esteemed Louise Doughty reached a swathe of new readers with her TV-adapted Apple Tree Yard—and her latest book cements her reputation.

"I think for a book that’s got an awful lot of death in it, it’s really about love, isn’t it?" muses Louise Doughty near the end of our conversation, which takes place at her publisher’s office in Bloomsbury. We are discussing Doughty’s ninth novel, Platform Seven, which has one of the most riveting first chapters I have read for a long time.

It begins at 4 a.m., Peterborough railway station. The only people around are a security guard and the on-duty customer services manager, and they both fail to notice the bulky middle-aged man who makes his way to the edge of platform seven and throws himself in front of a freight train. There is one witness, who tries to stop him—ineffectually, as it turns out, for we discover she is a ghost who died on the same platform 18 months earlier. Her name is Lisa Evans.

It begins at 4 a.m., Peterborough railway station. The only people around are a security guard and the on-duty customer services manager, and they both fail to notice the bulky middle-aged man who makes his way to the edge of platform seven and throws himself in front of a freight train. There is one witness, who tries to stop him—ineffectually, as it turns out, for we discover she is a ghost who died on the same platform 18 months earlier. Her name is Lisa Evans.

Platform Seven follows Lisa’s gradual unearthing of the events that led up to her own death, as well as her attempt to find out why the man killed himself. At the beginning of the novel she has no memories at all. She is able to "flow" around the living, watching them and listening to their thoughts, an omniscient narrator who only later starts to piece together her own memories to answer the question: how did she come to die? The novel flashes back in time to Lisa, alive, happy and full of enthusiasm for her teaching job, her friends, her boxy little flat. We see her meet a young doctor, a man with prospects, and begin what looks like a promising relationship. But it’s one which will take a less fairytale-like turn and lead, inexorably, to platform seven.

If Peterborough railway station sounds like an unusual setting for a novel, then that is Doughty all over. "I love capturing people and places that are not the usual stuff of contemporary fiction—that really excites me," she says. "Although, when I found myself writing a passage sitting in Burger King in Peterborough on a Friday night, that was less exciting, it has to be said. I thought about all the creative writing students I’ve had over the years—if only they could see me now, the wonderful, glamorous life of the novelist!"

On the rails

Doughty grew up in a small town in the East Midlands, from a non-literary background (she is one of the contributors to Kit de Waal’s Common People: An Anthology of Working-Class Writers). For years her journeys to and from her parents’ home involved changing trains at Peterborough railway station: she went to university in Leeds and then, after being accepted on to the MA Creative Writing course at the tender age of 23, to the University of East Anglia. (Recently she has led the crowdfunding for three scholarships for students from a BAME background in financial need.) "I’ve spent a lot of cold winter nights on that station with the wind blowing across the fens, it’s really bleak. I always used to say if I ever go to purgatory this is where I will find myself stuck!" she says.

A railway station is, she observes, a strange no-man’s land where passengers are in transition between one state of being and another. "It’s particularly potent if you are going home to visit parents, because you are actually catching the train back to your previous self, catching the train back to your childhood. You’re not just travelling in distance, you’re travelling in time. So, the idea of the railway station as a metaphor for purgatory and a kind of lost space in between our ordinary lives, struck me as really rich for exploration."

Although Doughty, previously nominated for the Costa Novel Award and the Women’s Prize for Fiction, had long been admired by readers of literary fiction, her career skyrocketed with the publication of her seventh novel, Apple Tree Yard. A bestseller on publication, it was adapted for BBC One as a major four-part series starring Emily Watson, and saw Doughty reinvented as a thriller writer. "I thought of Apple Tree Yard as a serious and feminist indictment of the criminal justice system," she says now, laughing, "and I have to say when people started calling it a thriller I was bit surprised."

Certainly, compared to literary fiction, crime sells in huge numbers. Given the enormous success of Apple Tree Yard, Doughty says now: "If I had been at all strategic I would have followed that up with another courtroom drama, but by the time it came out I was well into Black Water, a novel about political violence [in Indonesia]. That was just the idea that seized me. It was exactly the same with Platform Seven, I had this idea of a ghost haunting a railway station—and I just couldn’t let go of it."

In the novel Doughty knew she wanted to explore obsessive love, and the difference between love and possession. “Women are still ‘taught’ that when a man says ‘you belong to me’, that it’s a terribly romantic thing to say. ‘You belong to me, I kill anyone who touches you,’ all these things that we know now are very, very close to possession and coercive control."

It is testament to Doughty’s skill as a writer that although the reader knows that the worst has already happened (Lisa is a ghost, after all) the novel is so tense, and downright terrifying in places. Doughty was particularly interested in the "psychological ways in which somebody can be controlling or manipulative and the ways in which they can dismantle a person’s sense of themselves. That seemed to me something that is often very subtle and hard to detect—certainly hard to detect from the outside, if you are observing a relationship, but it’s even hard to detect when you are in the relationship itself."

We are taught to prioritise romantic love above all others, reckons Doughty, but the novel also explores other, perhaps purer, types of love: kindness, generosity, friendship. Platform Seven is dedicated to the late Andrea Levy, a close friend: "Our lives are made up of all those interweaving loves and romantic love is only one thread." In the novel, Lisa is able to sense the effect her death has had on those who knew her, the ripple effects moving outwards to engulf her best friend and her parents, and this is its true emotional heart.

It was only when she had finished writing the novel that Doughty realised that "something in me was excavating loss". Her own mother died in 2014. She had been thinking about "what we leave behind us when we die—is there any afterlife, is there any possibility of consciousness?" She doesn’t believe in an afterlife, apart from one thing: "I believe we live on in the hearts of the people who loved us."