You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Michael Cashman | 'I have to keep pinching myself every day I’m here'

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

From Albert Square to Parliament Square, Michael Cashman’s career has been varied, colourful and frequently star-studded, as he documents in his new memoir

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

"I have to keep pinching myself every day I’m here,” says actor, writer and politician Michael Cashman as he takes me on a personal tour of the House of Lords, his place of work since he was made a life peer in 2014. He shows me the brass hook where in former times he would have been required to hang up his sword. He does an excellent job as an art historian in the Royal Gallery, where we view two immense murals depicting the battles of Waterloo and Trafalgar. And then he sneaks me into the Pugin-tastic House of Lords chamber itself.

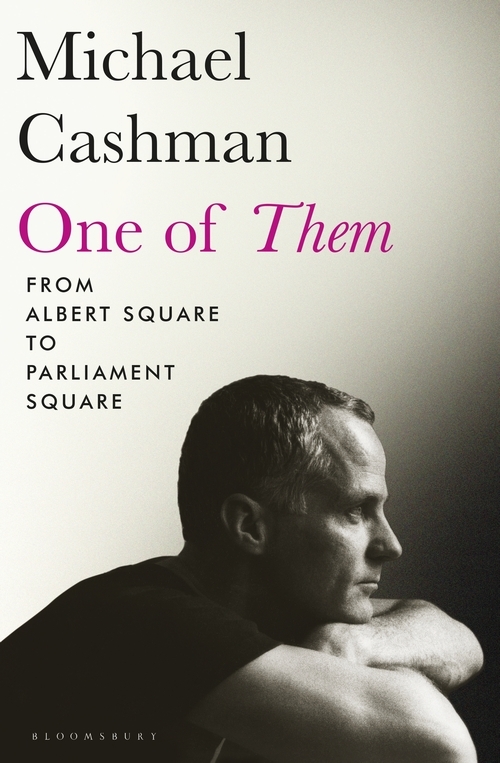

Now 68, Baron Cashman of Limehouse’s remarkable journey from the streets of the East End to the heart of Westminster is charted with great verve and honesty in his forthcoming memoir One of Them: From Albert Square to Parliament Square. The title comes from a remark his mother once made about her singing and dancing son: “I think he’s one of them.” It encompasses his tough working-class childhood; his time as a child actor on the West End stage; his role as Colin in EastEnders, who famously planted the first gay kiss on British television; his activism for Stonewall, the LGBT rights charity he helped found in 1989; and his 15 years as a member of the European Parliament, and then the House of Lords. Threaded through the politics are marvellous anecdotes aplenty, as well as a cast of characters which includes Mo Mowlam, Ian McKellen, Barbara Windsor, Elton John, David Hockney, Tony and Cherie Blair, Elizabeth Taylor and David Bowie, to name but a few. And at the core of the book is a love story: that of Cashman’s 31-year relationship with Paul Cottingham, his partner and later husband, who died from cancer at the age of 50 in 2014. In short, it is the memoir that has it all.

Now 68, Baron Cashman of Limehouse’s remarkable journey from the streets of the East End to the heart of Westminster is charted with great verve and honesty in his forthcoming memoir One of Them: From Albert Square to Parliament Square. The title comes from a remark his mother once made about her singing and dancing son: “I think he’s one of them.” It encompasses his tough working-class childhood; his time as a child actor on the West End stage; his role as Colin in EastEnders, who famously planted the first gay kiss on British television; his activism for Stonewall, the LGBT rights charity he helped found in 1989; and his 15 years as a member of the European Parliament, and then the House of Lords. Threaded through the politics are marvellous anecdotes aplenty, as well as a cast of characters which includes Mo Mowlam, Ian McKellen, Barbara Windsor, Elton John, David Hockney, Tony and Cherie Blair, Elizabeth Taylor and David Bowie, to name but a few. And at the core of the book is a love story: that of Cashman’s 31-year relationship with Paul Cottingham, his partner and later husband, who died from cancer at the age of 50 in 2014. In short, it is the memoir that has it all.

It’s been an incredible insight that if you have the courage to let yourself go in the writing, you can find out as much about yourself as the reader will.

“I wanted to write a memoir about two years before I stepped down from the European Parliament,” Cashman tells me over coffee in the parliamentary canteen. “I thought: ‘Come on, you’ve been an actor, you’ve done “EastEnders”, you’ve done Stonewall, you’ve done politics. Why don’t you put it down?’ But it became the meanderings of a maniac: it made no sense whatsoever. After Paul died, I wrote another draft but then it turned into a eulogy to him, really.” Cashman’s literary agent Robert Caskie encouraged him to take his time, while his now publisher Bloomsbury, having showed initial interest, decided the memoir wasn’t for them. “But about five months later, Alexandra Pringle got in touch to say, ‘We keep thinking about it.’” A re-draft later, Bloomsbury made a pre-emptive offer. What had changed? “I think I stripped out the eulogy and started writing more truthfully. I applied a rule from my acting days: namely that it’s much more moving to see someone trying not to cry. On the page that meant showing, not telling, and allowing the reader to feel it.”

A seasoned writer

Although One of Them is his first book, Cashman has form as a writer. In the early 1980s, he wrote plays for Alan Ayckbourn’s Scarborough-based company and at one point fancied writing for TV. His theatrical agent at the time was the legendary Peggy Ramsay, and Cashman, a brilliant mimic, does a marvellous impersonation of her (as he does of various people throughout our interview). “When I told her I’d quite like to write for television, she said: ‘No dear. Television is a factory that eats writers.’” Cashman’s recall for events is remarkable, and I ask him if he had diaries or other records to draw on when writing his memoir. “I did, but it was only afterwards that I went back and looked at my diaries, and I was astonished at what I had recalled. I think as an actor you get used to listening, and remembering: you have to remember in order to make a living. What I found staggering was the way in which the narrative almost directed itself: there were moments when I shocked myself about how I’d written certain things. It’s been an incredible insight that if you have the courage to let yourself go in the writing, you can find out as much about yourself as the reader will.”

Cashman is joyous company, but his intense blue eyes brighten and redden as he speaks of his late husband Paul whom he met in Scarborough when the then 19-year-old Cottingham was working as a redcoat at Butlin’s. The book is admirably frank about all the ups and downs of their three decades together. And it’s a shock to realise that for the first couple of years, their relationship was illegal: the age of consent for “homosexual acts” was lowered to 18 only in 1994, thanks in no small part to Cashman’s own campaigning (it is now 16). “It’s difficult enough trying to form any relationship. But when the law also criminalises it, is it any wonder that we came under pressure so often? And yet despite everything, we had the most amazing relationship. I think if Paul were alive, I couldn’t have written this book. It would have been a very different memoir: rather straightforward, almost predictable. And if I hadn’t placed him at the heart and core of it, I couldn’t have revealed all that I do.”

He is lavish in his praise for Bloomsbury, for Pringle and for his editor Callum Kenny, for not letting go of him on his emotional writing journey. And I quickly realise that it is typical of the man to constantly credit others. He greets many of the House of Lords staff by name, calling out a merry ‘good morning’ to the cleaner dusting the books in the library and speaking in beautifully accented French to the Francophone African lady on the till in the canteen. It’s clear that Cashman never forgets his East End roots, reminiscing about how he sometimes used to go along and lend his mother a hand with her job as a cleaner. “‘Off you go Mike, you do the ashtrays,’ she’d say. And here, without the cleaners, I can’t do my job. Without the caterers, I can’t get my food. I think we need to get back to connecting with other people much, much more,” he says.

Leaving Labour

Naturally, our conversation turns to politics. After 45 years, Cashman recently resigned his Labour membership in protest at the party’s refusal to make a pro-Europe stand, and what he sees as its growing intolerance and lack of action over antisemitism. He voted Liberal Democrat in this year’s European elections, but says: “In my head and my heart I haven’t left the Labour Party. But under its current leadership, it has left me.”

And this former MEP remains passionately pro-EU. “In 1939, Britain understood the concept of solidarity—‘Unless I stand with you, I will be next.’ We don’t get that now. We somehow believe that by being on your own, you become stronger. You don’t. You become more vulnerable. And I worry about the human rights landscape; I worry about whether we will remain within the Council of Europe, whether we will still have the European Convention on Human Rights. But I’ve got plenty of armour in my closet. I’m not in there, so there’s plenty of space,” he quips.

Asked what he is most proud of in his long career of politics and activism, Lord Cashman thinks for a while. “Coming out. Coming out, because that’s how I finally became myself. And until you own your space in the world, you can’t leave the world changed.”

Book extract

It was a cold December. But it wasn’t the cold that brought me into the world, it was a street fight outside Stepney East station. A group of men jumped my dad, fists and boots flying in all directions. My mum did the thing any decent wife would do, she waded in.

It was a vicious fight, she threw a few punches, extracted my dad and then they escaped home on a passing bus.

Inside their threadbare council flat my dad inspected his cuts and bruises and my mum let out a cry, clutched her stomach and, three weeks earlier than planned, went into labour with me.