You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Onjali Q Raúf | 'All of our deepest discussions start off with a very simple question'

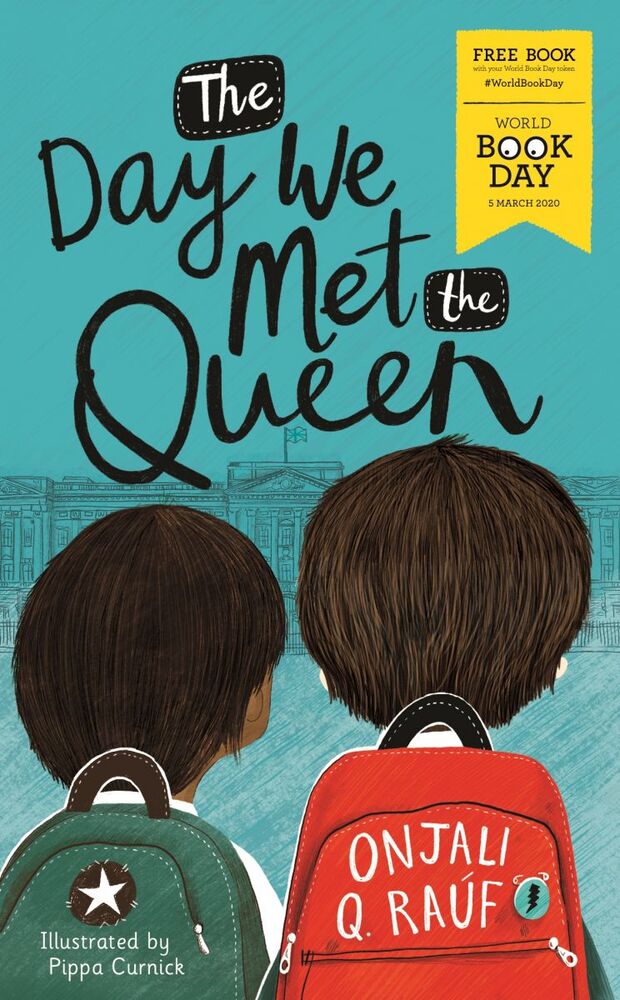

After her hit début, Onjali Q Raúf returns to the story of refugee Ahmet for World Book Day.

Few authors find themselves penning World Book Day £1 titles less than two years after the release of their début, but this is proof of the enormous impact of Onjali Q Raúf’s The Boy at the Back of the Class. Since publication in July 2018 the book has won the Blue Peter and Waterstones Children’s Book prizes, and has sold more than 120,000 copies. Full of both heart and hope, the story offers a child’s perspective on the refugee crisis, following nine-year-old Ahmet, who has fled Syria with his family and has been placed in foster care in the UK. For World Book Day, Raúf returns to Ahmet and his friends in The Day We Met the Queen.

“It’s a huge honour to be asked. World Book Day is such a big thing for any kid,” Raúf tells me when we meet at Hachette’s central London office. She vividly recalls the sense of freedom the World Book Day voucher granted from her own school days. “I thought, ‘Wow! This [choice] is mine. My mum and dad aren’t involved, school aren’t involved, I can pick any book I want.’” She hadn’t initially planned a sequel to The Boy at the Back of the Class, but says “it was really lovely to go back to the narrator’s voice and visit the kids again.”

When I go into schools and talk to kids and hear their questions, I come away with so much hope for the future, and I didn’t feel that before. The kids get it, the kids know

Although The Day We Met the Queen is a lighter story—“I didn’t realise there were going to quite so many things about farts and smells!”—the book touches on many of the same themes as its prequel, including racism, press bias and politics. Something Raúf did want to reflect was the divided country young people are growing up in. “I wanted to carry the conversation on about refugees, I wanted to carry the conversation on about the fact that people are divided over this.” The book features an incident where the children are surrounded by people from both sides of the political spectrum and hear passionate arguments from both perspectives. “They realise they are going to have to cut through that for themselves,” she explains. Inspiring children to think for themselves is at the heart of what she does. The book ends with a “very deliberate” notification that there are debates happening out there in the world. “You as a child, or a person on the cusp of adulthood, have a right to go out and find out what those debates are and ask questions for yourself, and to find people who will help you answer them.”

Although The Day We Met the Queen is a lighter story—“I didn’t realise there were going to quite so many things about farts and smells!”—the book touches on many of the same themes as its prequel, including racism, press bias and politics. Something Raúf did want to reflect was the divided country young people are growing up in. “I wanted to carry the conversation on about refugees, I wanted to carry the conversation on about the fact that people are divided over this.” The book features an incident where the children are surrounded by people from both sides of the political spectrum and hear passionate arguments from both perspectives. “They realise they are going to have to cut through that for themselves,” she explains. Inspiring children to think for themselves is at the heart of what she does. The book ends with a “very deliberate” notification that there are debates happening out there in the world. “You as a child, or a person on the cusp of adulthood, have a right to go out and find out what those debates are and ask questions for yourself, and to find people who will help you answer them.”

Raúf wrote throughout her childhood and beyond, inspired by literary heroines Jo March and Anne Shirley. “My favourites were always women who wrote.” She completed an adult novel at university, followed by eight years working on a trilogy about a world without chocolate. The latter earned her an agent but the book didn’t sell. She pursued a career working in women’s and human rights charities, most notably as founder and c.e.o. of Making Herstory, an organisation working to end the abuse and trafficking of women and girls worldwide. Then, in 2017, she became seriously ill and had to take time off for major surgery.

On her third day in hospital, the words “the boy at the back of the class” popped into her head. “It just wouldn’t leave me. I think when you’re in a lot of pain you start to think of all the people you wish you could have seen again.” One of the strongest images was of a baby boy, Raehan, who she had met in a refugee camp. “I started to ask myself, ‘Where is he now? What is he doing? What’s it going to be like for him if he does ever make it to the UK?’” The Boy at the Back of the Class, she explains, answers those questions in an “ideal” way. Housebound post-surgery, she wrote the book in just nine weeks. Two weeks after submitting it to her agent, Hachette acquired world rights in a significant pre-empt deal.

Her journey has been “absolutely mind-boggling, beyond a dream!” Why, I ask, does she think Ahmet’s story has captured imaginations in quite this way? Children, teachers and librarians, she believes, have made this book fly. Children, she asserts, are surrounded by news and images about the refugee crisis, about immigration and politics. “Children are hearing about it, it doesn’t matter how young or old they are, but there are very few places they can go and talk about it. The book is a safe place where they can ask these questions or have some of them answered.” Schools have also embraced the book. “I didn’t ever imagine kids would be studying it as part of their lessons. Teachers have found a tool they can use to have that conversation with the children.”

Young readers

From the refugee crisis in The Boy at the Back of the Class to domestic abuse in The Star Outside My Window, Raúf tackles issues more commonly seen in books for older children or teenagers. With protagonists aged nine and 10, how difficult is it to strike the balance between addressing important topics in an age-appropriate way while keeping the tone accessible and entertaining? “I think our inner voices are very childlike, for most of us,” she muses, “even if we don’t like to admit it. It’s not hard to tap into that when you have a space to do it. All of our deepest discussions start off with a very simple question.”

She is careful to lighten the darker moments of her books, for example the story of Ahmet’s sister, who passes away. “There was a debate about whether we should keep it in, whether it was too much. I knew we had to keep it in because it was a reality for so many refugee children.” The answer was “showing the pain of it” without showing the event itself. Similarly in The Star Outside My Window the events which lead to the children being fostered are off the page. “It leaves it up to the imagination of the person reading it.”

Raúf enjoyed weekly Friday trips to the library as a child, devouring everything from Frances Hodgson Burnett to Anna Sewell, Roald Dahl to Nancy Drew, but it was the Tintin books that opened a new world up to her. “It was the first book where I saw a character travelling to other parts of the world,” she tells me. “Egypt, Saudi Arabia, China. It made me realise there are other characters out there that looked a bit like me.” Tintin’s dog Snowy is now an integral part of her school events.

Raúf is incredibly passionate when she talks about meeting young readers. “One of the things I am absolutely more sure of than I have ever been of anything in my life is that we have an insurmountable amount of hope left in the world.” We don’t hear that, she says, in our news cycles or social media, which convey a sense of problems too big and people who are powerless. “When I go into schools and talk to kids and hear their questions, I come away with so much hope for the future, and I didn’t feel that before. The kids get it, the kids know.”

Photography: Rehan Jamil