You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

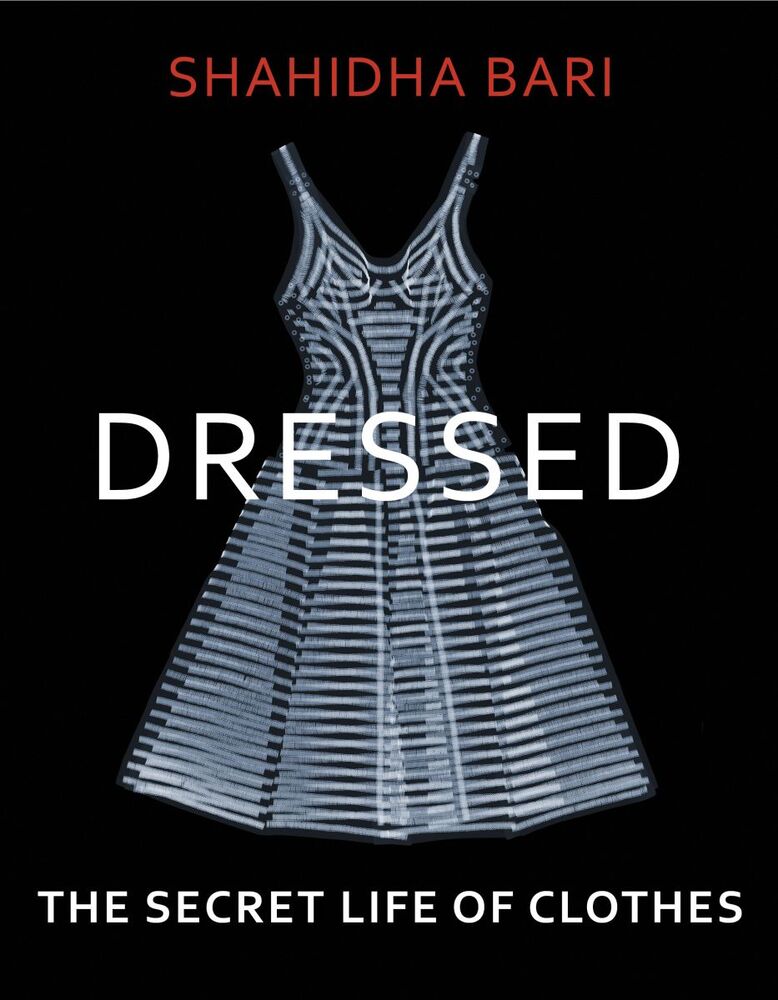

Shahidha Bari | 'Fashion is one of the most polluting industries in the world'

Shahidha Bari’s rumination on the function of clothing, as well as its depiction in art through the centuries, is a sprawling and illuminating read.

Clothes are so ubiquitous as to be almost invisible, in many instances by their wearer’s design. Yet few material objects so necessary to human existence are as flippantly treated: consider the gravitas and column inches often given over to food and shelter (i.e. "property"), which Abraham Maslow posits are equally essential as clothing to humans in his heirarchy of needs. Perhaps our concept of clothing has become too easily conflated with fashion, by its very nature fleeting and impermanent.

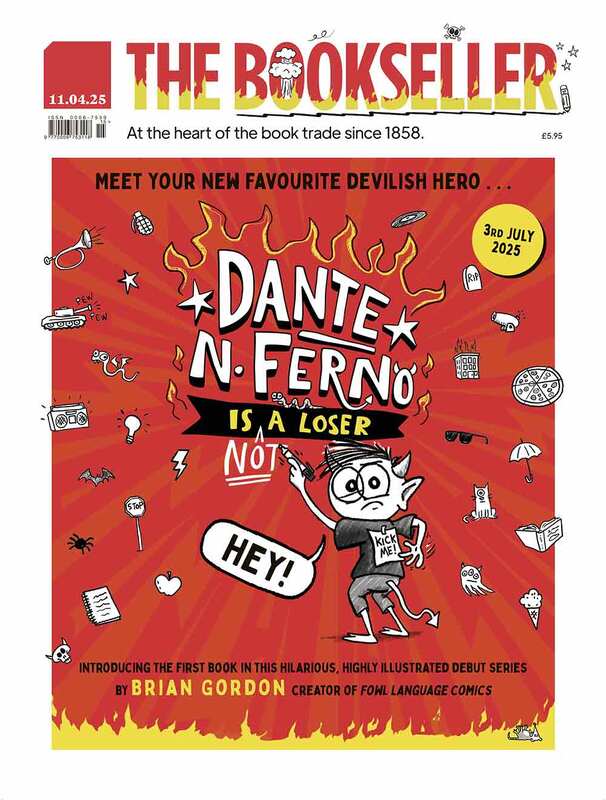

Shahidha Bari’s Dressed: The Secret Life of Clothes seeks to redress that. "Lots of people think that clothes are superficial or functional or not worthy of intellectual inquiry," she says. "If that is the case, why is it that they are everywhere, in literature, in film, in art, in music?"

It’s not so much that the subjects of those artforms are wearing them, but rather the attention that is given to such garments by artists: see the labourer’s battered leathers in van Gogh’s "Shoes", or Zinedine Zidane’s balletic footwear in "Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait", or the mismatched shoes Robinson Crusoe happens upon. All three are analysed in Bari’s book, which uncovers and knits together such allusions, with chapters split into Dresses; Suits, Coats and Jackets; Shoes; Furs, Feathers and Skins; and Pockets, Purses and Suitcases.

The breadth of references is remarkable, and Bari says it owes much to her work as an academic, cultural reviewer and BBC radio presenter, specialising in literature, philosophy and visual culture. "I spend my life watching films, visiting galleries and reading literature," she says, adding that she "already had a backlog" of interesting references to clothing in artforms before deciding to write the book some five or six years ago. "My weird brain was attracted and distracted by those things," she laughs.

Dressed is a meandering, enriching and sprawling read. Of its style, the author says that "you have to get really good at code-switching when you are an academic who works in culture", arguing that "philosophy in particular is a really arid, ugly discipline in terms of its language". Dressed is a far cry from that. "I worked really hard to make prose poetic: often it rhymes or there’s a rhythm... I wanted it to feel sort of, almost incantatory." Each chapter opens with a lucid, novelistic first-person soliloquy introducing the type of clothing under scrutiny, then delves into its genealogy and portrayal in popular (and less popular) culture, with a fair dose of philosophy, too.

When conducting research, Bari "couldn’t find the book that I wanted—that philosophical-cultural account of clothes, the experience of wearing clothes... clothes aren’t flippant, they are profound artefacts of our human experience. So I wanted it to have serious philosophy; I didn’t want to compromise on the ideas. But I wanted the experience to be beautiful—if you want someone to understand a lived experience, you have to make them live it."

Bari wanted the prose to be "evocative", and her literary influences are fittingly broad. She names Elena Ferrante (Dressed muses on the significance of Neapolitan quartet protagonist Lila’s shoemaking lineage); Roland Barthes ("he says really curious things; that the things that are part of our everyday life can be really profound"); art critic T J Clark and novelist Rachel Cusk ("I wanted their precision and sensitivity"); and James Baldwin ("there’s warmth to his intelligence—you never doubt how clever he is, and how kind"). She also notes that both writing and dressing have an element of "exactitude", arguing: "When you write, however you write, you are looking to capture that exact thing you are trying to describe. Clothes are like that, sometimes. You are looking to articulate that exact thing that you are, or the occasion you are going to. And you can hide in language, and clothes are about hiding, too."

Ways of seeing In the book she writes that she is "haunted by clothes", which is not to say she has a bulging wardrobe or a devout love of fashion ("fashion studies was new to me," she claims), but rather, it speaks of her method of apprehending the world. "Some of us have particular kinds of memory: some people are musical and attachsongs to things; my brother is a mathematical genius, and sees the world as numbers... my memory is very visual. I often attach colour and texture to people. I am slightly synaesthesic." Bari says she would remember my (wholly unremarkable) get-up were we to meet again, "because that is how my memory is organised—I’ll remember the things a person wears, the colour and the feel of those things, the sound of a zip or a button. Those are the things that my memory retains, weirdly."

In the book she writes that she is "haunted by clothes", which is not to say she has a bulging wardrobe or a devout love of fashion ("fashion studies was new to me," she claims), but rather, it speaks of her method of apprehending the world. "Some of us have particular kinds of memory: some people are musical and attachsongs to things; my brother is a mathematical genius, and sees the world as numbers... my memory is very visual. I often attach colour and texture to people. I am slightly synaesthesic." Bari says she would remember my (wholly unremarkable) get-up were we to meet again, "because that is how my memory is organised—I’ll remember the things a person wears, the colour and the feel of those things, the sound of a zip or a button. Those are the things that my memory retains, weirdly."

That is not to say that she is uninterested in clothing from an aesthetic or artistic point of view. Designers Yohji Yamamoto, Alexander McQueen and Walter van Beirendonck of the Antwerp Six are referenced, and Bari’s own experience of fashioning clothes was drawn upon, too. She learned to sew from her Bangladeshi mother—introduced in the author’s BBC Radio 4 documentary "My Mother’s Sari" in 2016—who "always sewed when I was growing up. If you are a first-generation immigrant, you aren’t going to find the clothes that you wore at home. She would buy yards of fabric, and sew. If you move between cultures, as someone like me, who is British Asian does, you have different registers of clothes. I was always conscious of different dress codes, cultural dress codes," she says, joking that her needlework skills were also developed out of necessity because "I’m small—I’m really tiny. So nothing ever fits."

Inseparable strands

The book chronicles thousands of years of clothed humans, yet Bari was a little reluctant to forecast their future. Ecological and welfare concerns are apparent throughout the book, notably in an analysis of an illustration of Cinderella by John Tenniel. His drawing muses on the plight of Mary Ann Walkley, a young seamstress worked to death after a near 27-hour shift; her case was also cited by Marx in Capital. Bari writes: The ballgown that brings life to Cinderella is the dress that brings death to Walkley... They are the two inseparable strands of one thread. Little has changed: in 2013 an eight-storey garment factory in Dhaka collapsed, killing 1,134 workers.

Yet Bari believes it is not straightforwardly a consequence of Western greed, narcissism or consumption. "The problem isn’t us buying—it’s overproduction as much as overconsumption. We have to stop blaming ourselves, and we have to challenge industry. I think that young women do buy a lot of clothes, that’s true, but they do it because there is a hole or an emptiness in life that they are trying to fill. I don’t blame them for that. I don’t blame them at all. I want to try and work out what that emptiness is. I don’t blame them for our environmental crisis—and we are totally in an environmental crisis. Fashion is one of the most polluting industries in the world.

"In a way, the whole project is driven by that. I didn’t want to write a polemical book, but I want you to think—when you put on your coat, or button your shirt—about what your clothes mean, who has made them." Bari says that to affect change, "we have to change our relationship with clothes, to take them seriously", because "if we care about our clothes, we might care about the people who make them. That’s the spine of the book, in a way. That is the secret life of clothes."

She has a more optimistic take on the aesthetic side, though. One could think mass production, low prices and ready availability of clothes, in addition to the increasing reach of media espousing a certain appearance, fashion or body type, may lead to a homogeneity of dress. Bari disagrees. "We complain about hipsters looking the same, or fast fashion, but human beings have never looked more different, precisely because they have so many different fabrics, colours, styles and shapes available to them," she says.

"We have this cross-cultural influence... it is miraculous and amazing to me, it’s endlessly exciting and interesting, that we have never looked more different. We’re lucky."

Book extract

The 1886 canvas in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is also, unmistakably, his, profoundly marked by that peculiarly heavy hand and rendered in the dulled browns of his Dutch Nuenen palette. The paint is thickly knifed, the pigment-clogged brush visibly scrubbed across the canvas next to vigorously cross- hatched textures. The brushwork is graceless, brutish, honest. So are the boots. They sit exhausted, reluctantly ordered like chided children, right and left in place, the battered leather robust and defiant, and the long-worn uppers curled from use. The laces are tightly threaded but left strewn, resting in the gleaming eyelets they have pierced. The lolling tongues dip into each boot’s dark internal recess. And yet they have the grace of the sunlit earth on which they rest. They rest. These boots have walked, have worked, and though they come to rest here on this sunlit earth, they are only momentarily stilled, as though they might labour yet with ragged breath.