You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

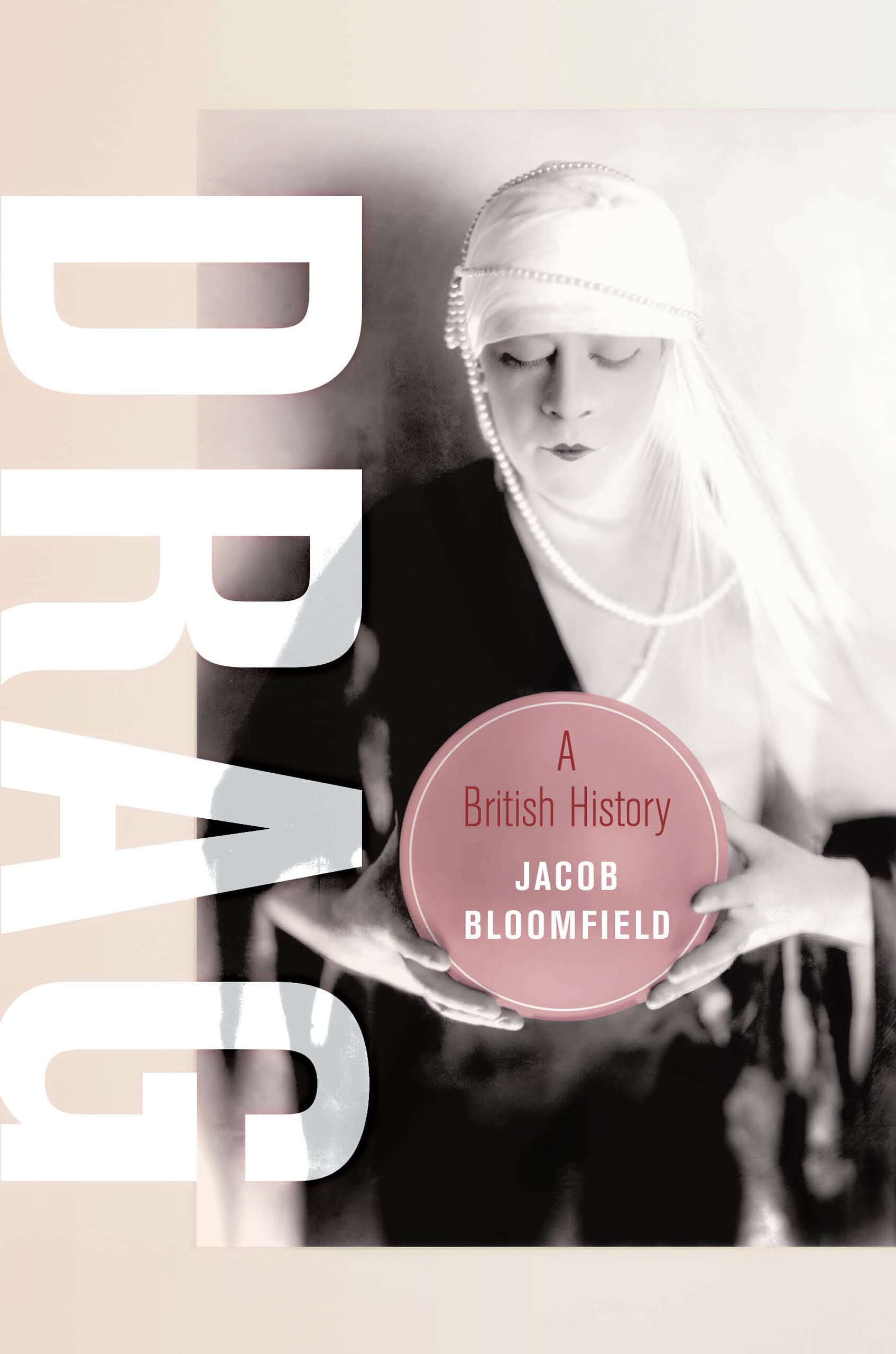

Jacob Bloomfield on his book about the history of drag in Britain

The library is officially open: queer culture historian Jacob Bloomfield on his century-spanning herstory of British drag, beginning in the 1870s.

In the past decade or so, there have been scads of hot takes about how drag is having a cultural moment because of the global success of “RuPaul’s Drag Race”. The reality show is wildly popular: the main US version is on its 14th season and the format has been spun off into 15 countries, not least “Drag Race UK”, which concluded its fourth BBC series on 24th November (for the record, I was team Cheddar Gorgeous from the off).

This has led to a dramatic uptick in audience numbers for live drag shows in general, a lucrative convention business has sprouted up—prices for a weekend pass to January’s DragCon 2023 at London’s Olympia begin at £90—and catchphrases and slang from drag culture have entered the lexicon.

There seems to be a bit of amnesia around drag: people are consistently taken aback by its supposed sudden popularity

Yet, squirrel friends, this is hardly the first time the theatre genre/sub-culture has had “a moment” according to queer culture historian Jacob Bloomfield. In fact, as he argues in his fascinating Drag: A British History (University of California Press), the current wave is just one of the many spikes in popularity over the past 150 years. Bloomfield says: “I do sort of laugh at these ‘drag’s cultural moment’ pieces in the wake of ‘Drag Race’. I’m not being contrarian by disputing that view, but we need to put it in a historical context. I have found articles going back to the 1870s essentially saying drag was having a moment—and again and again over the next century. So there seems to be a bit of amnesia around drag: people are consistently taken aback by its supposed sudden popularity. But in many ways, it has been at the heart of British popular culture.”

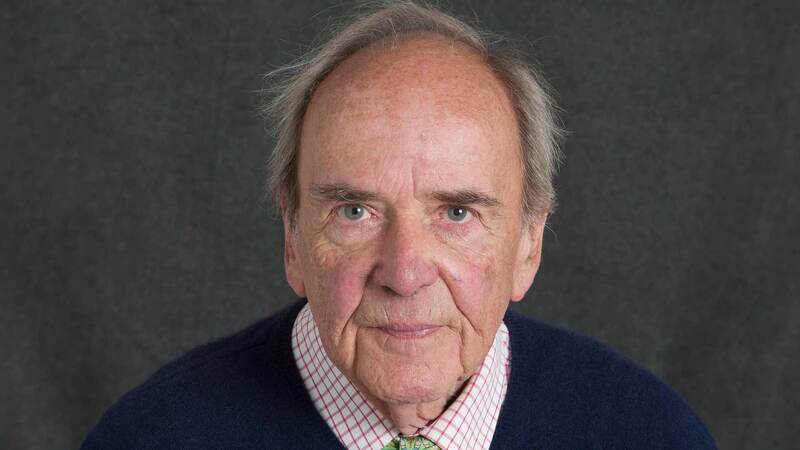

Brooklyn-born Bloomfield did his undergraduate and masters at the University of Edinburgh and his PhD in Manchester and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Konstanz in South-West Germany. But he is on a research trip to Japan when we meet over Zoom, for me at an unsociable early hour and he is gracious even though I arrive a dishevelled 15 minutes late thanks to my missing cat (long story, but Magwitch was located just moments before the call).

Bloomfield’s book spans a century of British drag history beginning in 1870, which he contends was when our modern sense of drag began, charged by the form’s popularity during the late-Victorian music hall boom. But he also uses the 1870 starting point as it was the year of a sensationalised cause célèbre in which Thomas Ernest Boulton and Frederick William Park—two drag artists who were a couple and cross-dressed in their private life—were arrested at the Strand Theatre in London and charged with “conspiracy to commit sodomy” (the two were later acquitted).

Bloomfield explains: “All those tropes we identify with drag—the pantomime dame, glamour drag—came into their own in the 1870s. I use a sort of simplified definition of drag [which boils down to] a performance that comments on gender, even if gender is not always a central theme. I realise that is a starting point and if someone argued that Elizabethan boy players [who acted the women’s parts] were drag, I really wouldn’t object. But I would say it wouldn’t be precise to call them drag because Elizabethan actors were in a time when women couldn’t be on stage—so they were operating in a completely different cultural context.”

Bloomfield explains that these tricky definitions are part of “a debate in queer history about labels. For example, whether you should call people in the past ‘gay’, ‘homosexual’ or ‘lesbian’ as those are terms they would not have applied to themselves. But my methodology is: do these modern terms help the reader’s understanding? And the first published use of the word ‘drag’ in the sense of male cross-dressing was in reference to Thomas Ernest Boulton, so I think I can safely describe him as a drag artist.”

At first glance, Bloomfield’s contention that drag has been at the heart of British popular culture may seem an overreach but he does make convincing arguments to back his case. Theatre was the dominant form of entertainment in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras and there were huge hits with drag at its heart, not least Brandon Thomas’ gender-bending 1893 play “Charley’s Aunt”, the original run of which was 1,466 performances, a West End record that would stand for decades. Some of music hall’s biggest stars—Dan Leno, Bert Errol, Vesta Tilley—gained fame from cross-dressing roles.

Drag bled into early radio and cinema. Entertainer Arthur Lucan brought his “Old Mother Riley” theatre act—a sort of prototypical “Mrs Brown’s Boys”—first to BBC radio and then to 15 films from the 1930s to 1950s.

Drag was incredibly popular amongst all kinds of audiences. What I was finding was very mainstream

One of the UK’s first talkies was 1929’s “Splinters”, the story of which was based around the real-life formation of a touring drag troupe made up of First World War veterans called Les Rouges et Noirs. The film was so popular it spawned two sequels. In fact, ex-servicemen drag revues had a long run with popular touring companies after the Second World War including “This Was the Army” and the rather on the nose “Soldiers in Skirts”.

And then there is the panto, which obviously is still a huge part of a British Christmas and has made scenery chewing dames like Christopher Biggins, Paul O’Grady and even Ian McKellen tidy sums. While panto’s crossdressing roots stretch as far back as the 17th century, Bloomfield says its modern incarnation began with music hall star Leno: “He didn’t popularise the dame in the panto but popularised the idea of the dame as the star of the pantomime.”

This huge success for British drag artists surprised Bloomfield: “When I first started my research, I thought I would be mainly looking into the subaltern and scandalous. And there is some of that, but part of the theme of the book is that drag was incredibly popular amongst all kinds of audiences. What I was finding was very mainstream.”

And yet as mainstream as those plays, films and TV shows became they were produced at a time when homosexuality was illegal in Britain. Was there some sort of disconnect with mainstream audiences watching these shows and the queerness of the content? “Some people acknowledged drag’s association with, let’s not say queerness, but sexuality,” says Bloomfield. “But the majority of people just went to these drag shows, had fun, enjoyed the campness and didn’t read into it. Or rather they knew exactly what was going on: I think we often believe we are so much more sophisticated than people of the past but they were just as savvy in picking up on sexuality and queerness.”

Bloomfield’s interest in drag is not just academic as he has performed at the Edinburgh Fringe and in London under his drag name Cupcake. This is not completely out of left-field as theatre was one of his first loves and Bloomfield attended New York’s LaGuardia High School, the performing arts-centred institution whose myriad of famous alumni include Al Pacino, Liza Minelli, Nicki Minaj and Timothée Chalamet. The obvious question: has his drag work affected his scholarship?

“I separate the two,” he says. “I’ve been encouraged to insert the performing side of myself into my academic work but I don’t see a way of doing it that isn’t contrived. Academics are obviously motivated by personal interest; a lot of, say, African-American historians tend to be African-American, a lot of Jewish scholars tend to be Jewish. Queer historians tend to be queer. Though it may be weird for me as a historian to say, I think while interest in the past is obviously great, it’s dangerous when we look to it for affirmation in our own lives. For example, does it matter if somebody was trans 100 years ago? Does that make being trans today any more or less legitimate? If the concept of being trans was invented yesterday, it would be just as legitimate. So, I personally don’t necessarily seek affirmation that there were drag artists a century ago, but my interest in drag history is obviously connected to other parts of my life.”