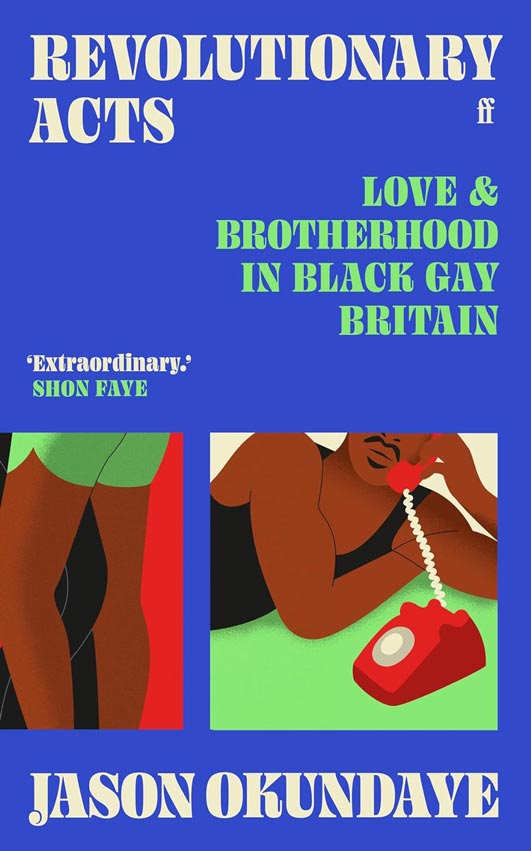

Jason Okundaye on his début book, Revolutionary Acts: Love & Brotherhood in Black Gay Britain

Journalist Jason Okundaye’s début book explores the history of south London’s queer, Black community, one human story at a time.

For many Black Britons, the south London area of Brixton is a diasporic homeland. It’s where the Black Cultural Archives can be found, documenting the history of the Caribbean and African people who moved to the city to help rebuild post-war. It’s the site of the Brixton uprising of 1981, where Black youths took to the streets to rally against the racial discrimination enforced by the police. It’s also one of the few places in London where plantain and yams can still be bought in bulk, for a reasonable price, on the backstreets of Brixton Market. What’s seldom known, however, is that it was once a place of significance for an underground Black gay community in the 80s and 90s. Through his début book Revolutionary Acts: Love & Brotherhood in Black Gay Britain, writer Jason Okundaye tells the largely unheard stories of the men who truly made Brixton their home: despite the discrimination imposed against them.

A south London native (he grew up in Battersea), Okundaye began his career working within policy for Westminster, where writing was more of a hobby that he indulged in on the side before shifting into becoming a full-time writer. “Originally, I started out doing political commentary writing, then I found I much preferred writing about culture,” he says with an earned confidence. His X account serves as testament to his cultural shrewdness, commenting on everything from the reality TV series “Love Island” to his misgivings towards the Tory party.

Professionally, his words regularly appear in leading publications: whether sharing his musings in the Guardian or profiling top talent for GQ. After acquiring an agent, Okundaye was asked if he had any ideas for a book; the inspiration would come from Marc Thompson, one of the subjects of Okundaye’s undergraduate dissertation that he set out researching in 2017. “He’s someone who was diagnosed with HIV at a very young age and has that experience of alienation, fear and this real sense of impending doom, but he was able to live a full life and be present today to tell me his story of surviving this,” the author explains with perceptible reverence. The more Okundaye spoke to Thompson, the more he began to discover what existed just beneath the surface. “People kept speaking about other people who lived in the same building as Marc or lived on the road parallel to him,” he says. “I got this sense of this community in Brixton and thought I need to discover these men, chat to them and really learn about their lives.” Other than Thompson, Ted Brown, Dirg Aaab-Richards, Alex Owolade, Calvin “Biggy” Dawkins, Dennis Carney, and Ajamu X are the real life characters who proffered their candidness for Okundaye’s work.

Initially daunted by the prospect of recording the men’s stories as a book, Okundaye found that the process came naturally to him. “After years of writing for magazines and newspapers, it genuinely felt thrilling to think ‘the page is mine and I can write what I want to here’,” he says, although he was sure to remain conscientious of why he wanted to write a book in the first place. His intention was never to craft “this detached, dry historical study” but to earnestly delve into the men’s lives. “They have so much written in their history and have contributed so much to this country that I thought it would be a shame for their identities to be gone,” he says.

Okundaye’s narrative tone is also distinctly sincere. “People put the Black trauma narrative against the Black joy narrative. I’m not interested in whether the book is too traumatic or if it’s going to be joyful and uplifting—I’m more interested in what’s real and that’s it,” he explains. Although a work of non-fiction, Revolutionary Acts was inspired by the fictional novel The Lonely Londoners by Sam Selvon, which traces the fabled lives of African and Caribbean migrants who settled in the city after the war. Okundaye depicts love affairs that culminate in heartbreak or death and coming out stories that end in crushing twists with emotional deftness. “When people read this book, I don’t want them to just read what happened—I want them to get to know these men as people,” he explains, adding that the men, in a sense, have become his friends.

I’m not interested in whether the book is too traumatic or if it’s going to be joyful and uplifting—I’m more interested in what’s real

It’s for this reason that his main concern was what the men would think of the book. “Each one of them has said to me that they’re really glad I didn’t just write a whitewash,” he says, with a modicum of relief.

The author graciously notes that from a commercial standpoint, people from all demographics have positively reviewed the book. “I got reviews in the Guardian and in the i and a mini brief in the New Statesman, which I’m grateful for,” he says. “Although, there were books and papers that were reviewing gay books but they weren’t reviewing mine. I can’t speak to why they haven’t; all these books about white gay men get serious consideration but mine has not. I tried to not internalise it or feel a way about it.” He says this with full awareness that he may “eat [his] words”, as reviews can sometimes follow months after a book’s publication. However, The Bookseller reported last year that publishers are potentially letting Black authors down after noting a steep decline in Black-authored bestsellers since the Black Lives Matter movement, suggesting Okundaye’s reflections likely aren’t unfounded.

As a proud Black gay man himself (a comment Okundaye makes in the book’s introduction), his opinion of the book, like his narrative intent, is straightforward: “I’ve got something that I feel is quite rich and beautiful, and I wouldn’t have written it any other way.” However, that’s not to say that the writing process itself was without difficulties. Within the pages, he references the Channel 4 documentary series “The Black Bag” that aired during the 90s, which spotlights racial issues in Britain. Recently, he wrote a piece for the Guardian about his search for an episode called “Blackout”, which includes one of his subjects (Dennis Carney). After perusing YouTube, the Channel 4 archives and the British Film Institute’s Black Britain on Film collection, he still couldn’t find it. Luckily, Carney had recovered a misplaced copy on VHS that Okundaye laboriously transferred to a USB stick. “I remember I watched it and felt quite upset watching it, and I didn’t expect to feel that upset,” he says. “I felt something deep when watching that documentary and it helped me to view Dennis in a certain way.” Evidently, veering away from being a “detached outsider” to add profundity to his book was not without emotional cost for the author.

Humanity may be at the crux of Revolutionary Acts but Okundaye personifies Brixton in the sense that it becomes a leading character in and of itself. “I thought maybe I need to write something about the whole of the UK or the entire expanse of London, but then I thought, no, actually, I’m going to write about this particular place,” he says. The writer eulogises Railton Road where many of the men lived, Windrush Square, which acted as a meeting spot, and highlights father figure Patrick Liverpool’s former safe house. “When I went to the address where he used to live on Morval Road in Brixton, it had been converted into a flat share,” he explains, the disappointment tangible. “This place for all of these young Black gay men was just not there anymore. It showed me how quickly things can be taken away and deteriorate.”

When asked whether he thinks his book will be relevant for future generations of Black British gay men keen to retain their history, he’s undecided: “We don’t know what’s going to matter for posterity or what people are going to be interested in.” Let’s hope Revolutionary Acts will be stored safe somewhere in the future, like Carney’s VHS tape, and that there will be an eager individual present, determined to decode its messages.